Light, Time, and Sacred Rhythm

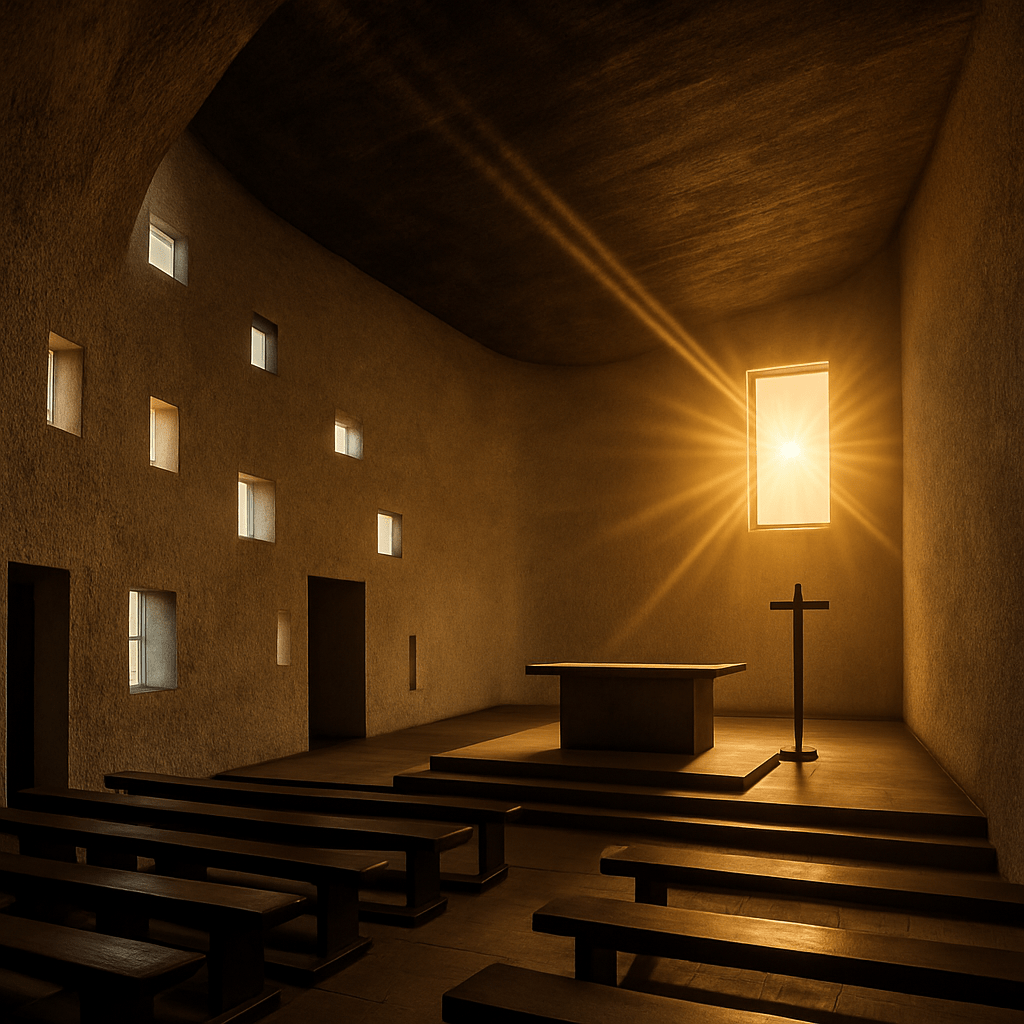

When I was a student researching the role of light in sacred architecture, I visited a Benedictine monastery that left a lasting impression. The modern church on its grounds, though recently built, followed the medieval principles of the order with striking fidelity.

The monk guiding the tour explained something quietly profound: the entire structure was aligned east to west, just as monasteries had been for centuries. The entrance faced west, symbolising the end of the day, while the apse—housing the altar—faced east, where the sun rises.

Light draws the eye along the east–west axis, from the dimly lit choir to the glowing stained-glass apse. In sacred architecture, orientation is not arbitrary—it’s a quiet choreography of shadow, rhythm, and reverence.

Photo by Patricia, Westminster Abbey, London (2025)

In the stillness of dawn, when the monks gathered for their first prayer, sunlight poured through the stained-glass windows behind the altar. It wasn’t just a beautiful effect. It was a message—one designed into the building itself. Time passed, not by the ticking of a clock, but through the slow choreography of light.

At midday, a shaft of light entered through the raised structure at the crossing of the transept—right at the intersection of the church’s arms. At that moment, vertical light descended like a silent blessing.

The monks prayed not once but many times a day—Matins, Lauds, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, Compline. Each hour, the light shifted. Morning light from the east; noon light from above; evening shadows cast from the west. It was as if the building itself participated in the prayer—a living sun clock, guiding the body and spirit through light.

During the summer solstice, sunlight rises directly above the Heel Stone and enters the circle, aligning sky, stone, and season in one ritual gesture.

Photo by Andrew Dunn / Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Sacred Orientation: Light, Ritual, and Cosmic Order

Across civilisations, sacred buildings have long been aligned with the path of the sun. This orientation was never merely functional—it was symbolic, ritualistic, and cosmological. It reflected a deep desire to anchor human experience within the rhythms of the cosmos.

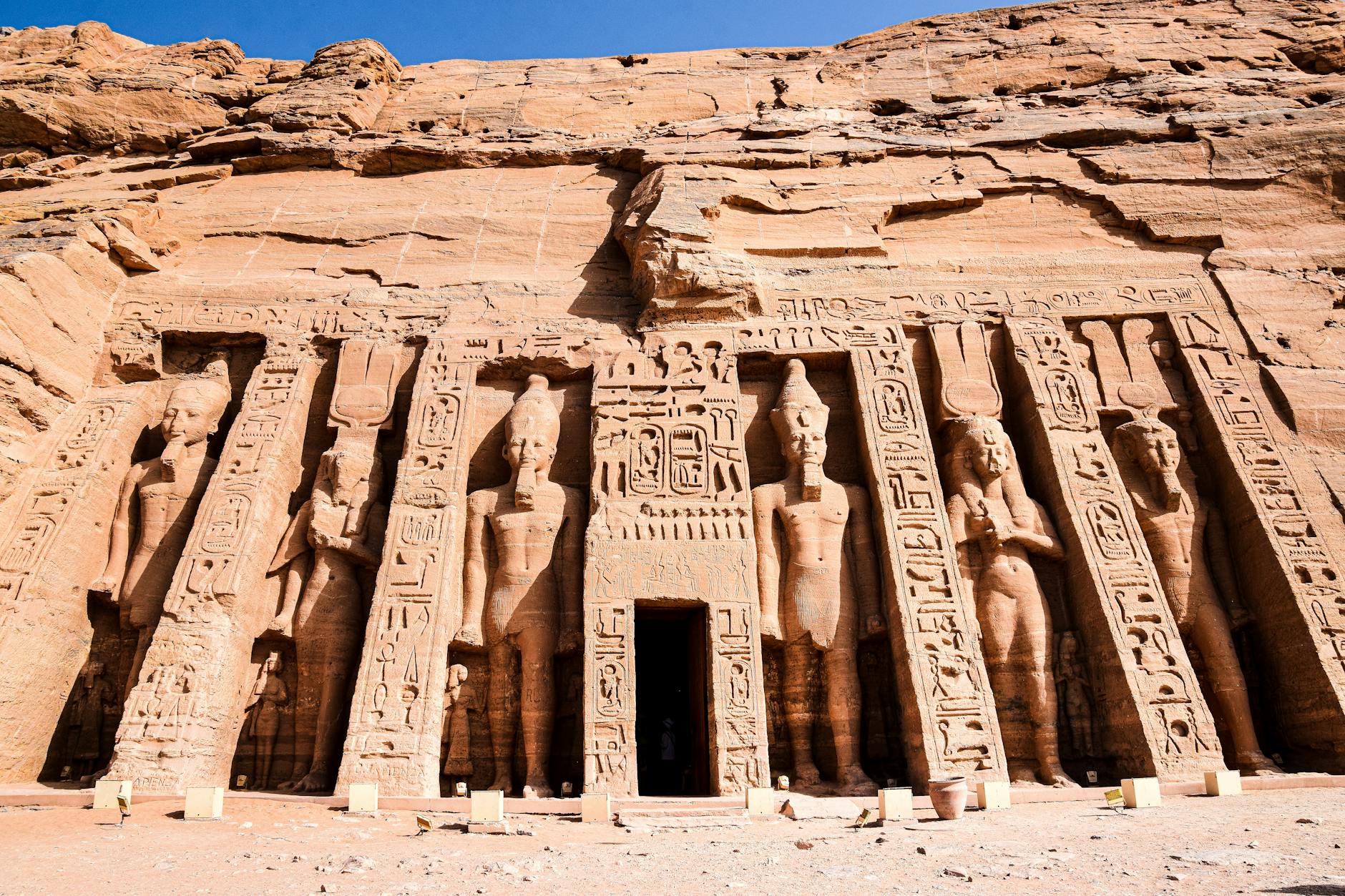

The Great Temple of Ramesses II (left), dedicated to the gods Ra-Horakhty, Amun, and Ptah, and the Small Temple (right), honouring the goddess Hathor and Queen Nefertiti. Together, they form a sacred complex carved into the cliffs of Nubia—where solar alignment, divine presence, and royal legacy converge.

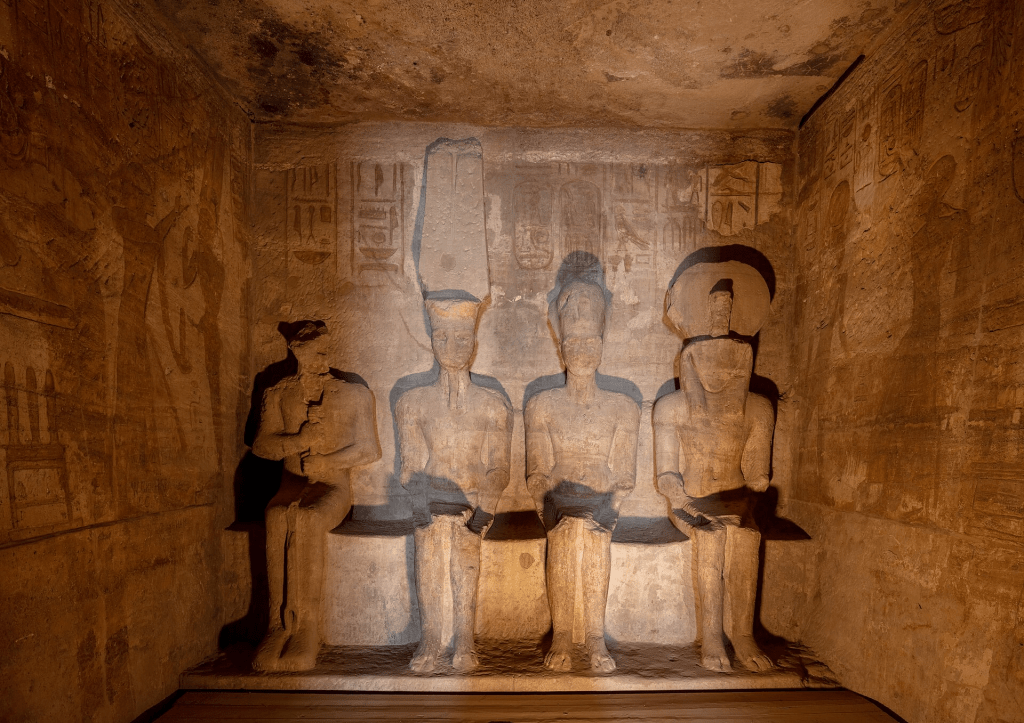

Twice a year—on February 22nd and October 22nd—a beam of sunlight travels through the temple of Abu Simbel and reaches its innermost sanctuary, illuminating the statues of Ramses II, Ra, and Amun. The fourth statue, Ptah, god of darkness, remains untouched by light—just as intended. This solar alignment, crafted over 3,200 years ago, originally marked the pharaoh’s coronation and birthday. Even after the temple’s relocation in the 1960s, the phenomenon continues with astonishing precision. Abu Simbel is more than a temple—it’s a monumental solar calendar.

Photo by Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0

Ancient Egypt

The temples were often built along the east–west axis so that the rising sun could symbolically enter the sacred space, representing divine presence and cosmic renewal. Monumental pylons at the entrance evoked the horizon (akhet), the gateway between the peaks through which the sun would rise and set. These alignments were not only spatial but temporal: some temples, like Abu Simbel, were designed so that sunlight would penetrate the inner sanctuary only twice a year, coinciding with the pharaoh’s birthday and coronation—turning light into an instrument of royal divinity.

Yet, Egyptian architecture also shows remarkable variation. Luxor Temple, for instance, is oriented along a north-south axis—not to the sun, but to connect it ceremonially with the Karnak complex, a route walked during the Opet Festival. Here, orientation served procession and myth more than solar geometry.

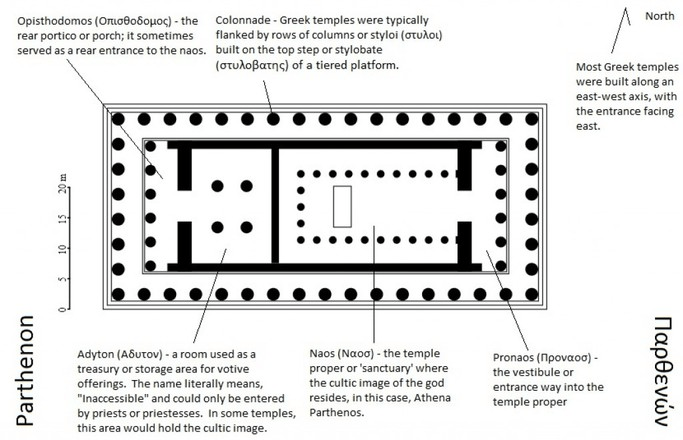

A typical Greek temple with east–west orientation. The inner naos housed the statue of Athena, while the adyton served as a sacred treasury. Entry was through the pronaos, and the structure was framed by a surrounding colonnade.

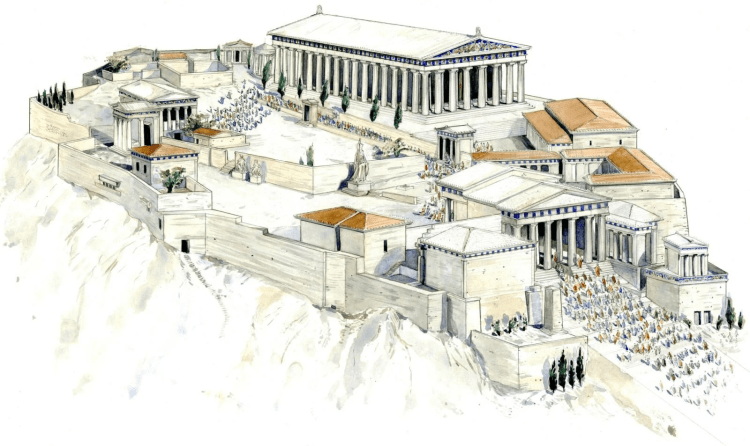

Left: Reconstruction of the Acropolis, showing the Parthenon within its sacred complex. Drawing by Kate Morton.

Right: Modern replica of the colossal statue of Athena Parthenos inside the Parthenon in Nashville. Designed to reflect the grandeur of the original, the statue stood in the eastern chamber, lit by natural daylight and reflected in a shallow water basin.

Greece

Similarly, Greek temples often faced east to welcome the morning sun. But not always. The Parthenon in Athens, for instance, does not follow a strict east–west alignment. Instead, it is slightly rotated to the northeast. Recent archaeological simulations suggest that, during the Panathenaea Festival in late July, the rising sun entered the temple and illuminated the statue of Athena Parthenos—especially her golden robe.

This subtle but powerful phenomenon lasted only a few minutes and may have been designed to evoke divine presence, reinforcing the connection between architecture, ritual, and light.

North America

The ancestral Puebloan complex at Chaco Canyon was designed with astonishing astronomical precision. Ceremonial spaces like the Great Kiva and Casa Rinconada track solar and lunar cycles, aligning with solstices and equinoxes. Architecture became a celestial calendar—stone aligned with sky.

Across these cultures, sacred orientation was far more than alignment. It was meaning. Through shadow and sunlight, through axis and ritual, ancient architects created not just buildings—but instruments of cosmic harmony.

This ceremonial structure, built by the ancestral Puebloans, is aligned with solar and lunar cycles. Its design reflects a deep cosmological understanding, where architecture served not just as shelter, but as a tool to track solstices, equinoxes, and celestial events—linking earth, sky, and ritual.

From Antiquity to Monasteries

Medieval Christian builders inherited this language of light. Though the beliefs changed, the orientation endured. Early Christian basilicas, Romanesque monasteries, and Gothic cathedrals all kept the sun’s path in mind. Their layouts preserved the idea that entering a sacred space meant moving from west to east—from the fading light of the world into the promise of divine illumination.

The church became more than a shelter—it was a spiritual sundial. A silent reminder of the rhythms that link the human with the divine, the earth with the sky. Throughout the day and the seasons, light and shadow choreographed a sacred dance. And through stained-glass, architecture told stories of faith in colours that spoke without words.

Clerestory windows encircle the dome creating the illusion that it floats on a ring of light. Built in the 6th century, this architectural masterpiece channels daylight to evoke divine presence—lifting structure into spirit.

Photo by Francesco Bini / Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Light as a Spatial Calendar

In monasteries, light marked the hours of devotion. In temples, it tracked the solar year. In both, architecture choreographed the sun.

Though centuries have passed, the sun remains a design partner. Modern architects, like their predecessors, are still shaping light into meaning. Ando’s Church of the Light uses a single cross-shaped opening to direct sunlight onto the altar. Kahn’s Salk Institute uses a water channel to reflect the setting sun between two facing wings.

These designs are low-tech yet deeply expressive. No sensors, no automation—just sunlight, form, and intention.

When designed with care, architecture becomes a calendar made of shadows.

Beyond Illumination: Designing with Light as Language

In contemporary practice, light is often treated as a technical variable. But throughout history, it has been a storyteller.

Walls, openings, niches—when placed with purpose—can speak in sunlight. A morning-lit corridor can evoke clarity. A shadowed sanctuary can summon awe. A golden-lit room at dusk can invite reflection.

We explored this in our article on Light and Shadow, where we showed how contrast gives depth and meaning to space. Together, they form a language that requires no electricity—only design.

Let’s shift the conversation—from lighting as control, to lighting as story.

From high-tech dependency, to low-tech intelligence.

The question is not: What fixture should go here?

But rather: How can this wall, this opening, this material, speak with the sun?

To design with light is to design with time, with nature, and with care.

Because when light is treated not as a tool but as a message,

architecture becomes more than structure—it becomes meaning.

References

On the orientation of ancient Egyptian temples: Upper Egypt and lower Nubia. https://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/nph-iarticle_query?bibcode=2005JHA….36..273S&db_key=AST&page_ind=0&data_type=GIF&type=SCREEN_VIEW&classic=YES

The Parthenon Sculptures. https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/contested-objects-collection/parthenon-sculptures?utm_source=chatgpt.com

An introduction to the Parthenon and its sculptures. https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/introduction-parthenon-and-its-sculptures

The Center of an Ancient World https://www.nps.gov/chcu/index.htm

Exploring Chaco Canyon: A Journey into New Mexico’s Ancient Heart. https://otbttravel.au/exploring-chaco-canyon-a-journey-into-new-mexicos-ancient-heart/