Would you teach maths or grammar in a gym?

Most people would say no. We tend to assume that serious subjects require serious settings. But is that really how the brain learns best?

For centuries, education has treated the mind as something separate from the body, confining learning to desks and straight lines. Yet today we know that the brain — the primary organ of learning — thrives through movement, emotion and sensory experience. And still, we continue to put obstacles in its way.

The current model of schooling was born at the end of the eighteenth century, at a time when scientific knowledge of the brain was almost non-existent and the aim was to produce factory workers: disciplined, silent and efficient. That model persists even now, despite the evidence offered by neuroscience: the brain learns through exploration, curiosity and embodied experience.

If we do not teach in the way the brain learns and flourishes, perhaps we are not truly teaching… just repeating old bad habits.

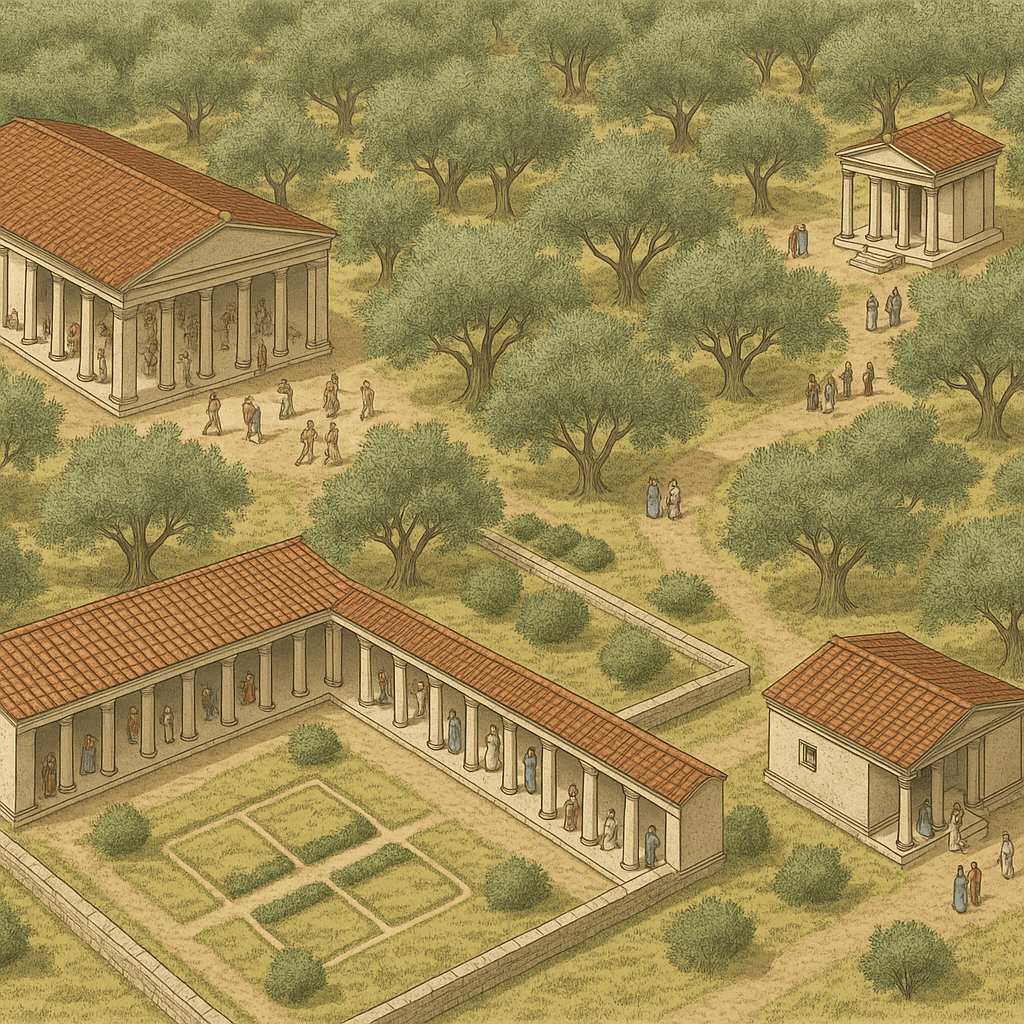

Plato’s Academy stood in a sacred grove, beside a gymnasium: a space both for physical exertion and for intellectual dialogue. There were no rigid classrooms or authoritarian teachers. Learning emerged through walking, questioning, discovering together.

For the Greeks, nearly 2,400 years ago, movement was inseparable from thought.

What science says about movement

Movement does more than activate muscles — it also activates the mind.

Whenever we walk, jump, or handle an object, we stimulate brain networks involved in attention, memory, and emotional regulation.

- The cerebellum, traditionally linked to motor coordination, communicates with the prefrontal cortex to refine thought, language, and decision-making.

- The hippocampus, key to memory, is more active when the body is moving.

- Dopamine, the neurotransmitter of motivation, increases with physical activity, favouring focus and curiosity.

It is no coincidence that many of us remember ideas best while walking, or that children learn more quickly when they can touch, move, or build. The mind is not confined to the brain: we learn with the whole body.

Learn by doing

Recent research in education and neuroscience is clear: students who learn actively — moving the body, manipulating materials, dramatizing concepts — understand and remember better than those who remain seated, listening.

In programmes like Thinking While Moving in Maths (University of Newcastle, Australia), children learn mathematics by running, jumping or sorting objects in motion. The results are compelling: motivation increases, anxiety decreases, and retention of concepts improves.

Even something as simple as a five-minute active break between classes yields measurable impact. Attention returns, memory consolidates, behaviour improves. Moving is not a distraction: it is a learning strategy.

Designing for Learning in Motion

If the brain needs to move, classrooms must keep up. The physical space is not neutral: it teaches just as much as the content.

A neuro-compatible classroom should allow three fundamental things:

- Flexibility: mobile furniture, zones in which to move, floors where work can be done standing, seated or on the ground.

- Connection with nature: large windows, terraces, courtyards and outdoor paths that invite sensory exploration.

- Spatial diversity: corners for concentration, open areas for group activities, and intermediate zones for free interaction.

Natural light, soft colours, and warm materials help the nervous system maintain calm and attention. Architecture can — and must — become a pedagogical tool: an extension of the brain and of the body that learns.

Schools that inspire

1. Fuji Kindergarten in Tokyo — designed by Tezuka Architects.

This kindergarten follows the Montessori method, which allows children to move freely and learn through exploration. Rather than imposing limits, the architect conceived an open building without physical boundaries, where learning and play flow naturally.

The circular rooftop allows children to run, observe and explore in motion — up to six kilometres a day — making the body an active part of thought. Architecture becomes a guide, stimulating and supporting without restricting.

Tezuka defines his vision as a “nostalgic future”: recovering the freedom and curiosity of spontaneous play, but through a contemporary design that fosters creativity and well-being. The project has been awarded the Moriyama RAIC International Prize for its transformative impact on education and society.

2. Vittra Telefonplan School in Stockholm — designed by Rosan Bosch Studio.

In the Swedish educational network Vittra, learning is not organised by classes or subjects but by levels and types of experience. Their architecture reflects this pedagogy. Rather than closed classrooms, environments are based on five metaphors: “the watering hole,” “the campfire,” “the cave,” “the show-off,” and “the laboratory.” Each embodies a different mode of learning: sharing knowledge, silent reflection, experimentation, dialogue, or presentation.

In Vittra Telefonplan, desks vanish. Instead, there are mounds for debate, caves for concentration, amphitheatres for presentation and open zones where students choose how and where to work. Spaces adapt to the learning pace, not the other way around. Mobile furniture, soft textures and vibrant colours stimulate curiosity and autonomy.

This design seeks to break traditional hierarchies between teacher and student. Architecture encourages self-organisation, collaboration and critical thinking — core values in Vittra’s pedagogy. Here, learning is an act of exploration: the environment invites movement, interaction, and appropriation of space as an extension of cognition.

3. Saunalahti School in Espoo — designed by Verstas Architects.

Saunalahti’s architecture was conceived to amplify contemporary pedagogy and promote active learning. Designed as a genuine “learning landscape,” it integrates terraces, ramps, and transparencies that invite movement, exploration and visual interaction between spaces.

Each corner encourages collaboration and curiosity: students may move freely, observe, engage and discover. The building opens into its natural surroundings, creating continuity between interior and exterior that stimulates the senses and strengthens connection with the environment.

A special emphasis is placed on art and physical education, integrating them as pillars of holistic development and pupil well-being.

When the body moves, the brain awakens.

And when space encourages movement, learning occurs.

Toward a new pedagogy of space

If we accept that learning flourishes when the body moves, school architecture must evolve with that evidence. Classrooms of the future will not be enclosed spaces, but dynamic ecosystems, where moving, thinking and creating become part of the same process.

The challenge is no longer to keep students still, but to design environments that transform movement into knowledge. Flexible spaces, without rigid barriers, that encourage collaboration, exploration, and well-being.

Every corner will have a purpose: to inspire curiosity, invite discovery and make learning a living experience.

When the body is active, the mind awakens — and architecture becomes a companion inviting us to explore, move and learn within safe, inspiring environments.

References

Bédard, C., St John, L., Bremer, E., Graham, J. D., & Cairney, J. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of physically active classrooms on academic achievement. PLoS ONE, 14(6), e0218633. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218633

Gallese, V., & Lakoff, G. (2005). The brain’s concepts: The role of the sensory–motor system in conceptual knowledge. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 22(3–4), 455–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643290442000310

Hillman, C. H., Erickson, K. I., & Kramer, A. F. (2008). Be smart, exercise your heart: Exercise effects on brain and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(1), 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2298

Koziol, L. F., Budding, D. E., & Chidekel, D. (2012). From movement to thought: Executive function, embodied cognition, and the cerebellum. Cerebellum, 11(2), 505–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-011-0321-y

Ratey, J. (2008). Spark: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain. New York: Little, Brown and Company.

Watson, A., Timperio, A., Brown, H., Best, K., & Hesketh, K. D. (2017). Effect of classroom-based physical activity interventions on academic and physical activity outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0569-9

Educación 3.0. (2023). El cerebro en movimiento aprende más rápido. Recuperado de https://www.educaciontrespuntocero.com/noticias/neurociencia-movimiento-cerebro/

Educación 3.0. (2024). Estos son los beneficios de los descansos activos en el aula. Recuperado de https://www.educaciontrespuntocero.com/noticias/beneficios-descansos-activos-aula/

Educación 3.0. (2024). Aprender matemáticas a través de la educación física, ¡éxito asegurado! Recuperado de https://www.educaciontrespuntocero.com/noticias/matematicas-a-traves-de-la-educacion-fisica/