What happens when buildings are designed not just for shelter, but to support how we think, feel, and interact? This question guided the creation of one of the most innovative neuroscience centres in the world: the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre in London.

Where Vision Meets Neuroscience

Between 2009 and 2016, British architect Ian Ritchie was commissioned to design the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre (SWC), a neuroscience research facility in London focused on understanding how brain circuits process information to form neural representations and guide behaviour.

The project began in 2007 when Lord Sainsbury of Turville founder of the Gatsby Computational Neuroscience Unit, eager to accelerate progress in neuroscience, consulted British neuroscientist Dr Sarah Caddick. She recommended integrating theoretical and experimental scientists to better understand the relationship between theory and biological reality.

By 2008, the Wellcome Trust, a global health research foundation, and University College London (UCL) had joined the initiative, with UCL providing experimental scientists. All parties agreed on one priority: functionality.

The program

- Based on past frustrations with poorly designed laboratories, they decided the new centre should be built from the inside out, placing the scientists’ needs before aesthetics.

- Crucially, the building needed to ensure that theoretical and experimental scientists would naturally intersect at multiple points throughout their day and across varied contexts—sparking informal dialogue, unplanned collaboration, and the exchange of ideas.

- They also agreed that the building should be adaptable to evolving research needs, with a 60-year design outlook.

- The team committed to incorporating principles of neuroarchitecture showing how our environments affect mood, behaviour, and cognitive performance—all with the goal of boosting productivity.

Instead of presenting a fixed design, Ian Ritchie proposed an open-ended research process to explore and test ideas collaboratively. This approach would become a hallmark of the project.

Learning from the Salk Institute

Design research began in 2009, lasting nearly a year. Ritchie and a team of architects and neuroscientists toured prominent neuroscience labs across the US and Europe.

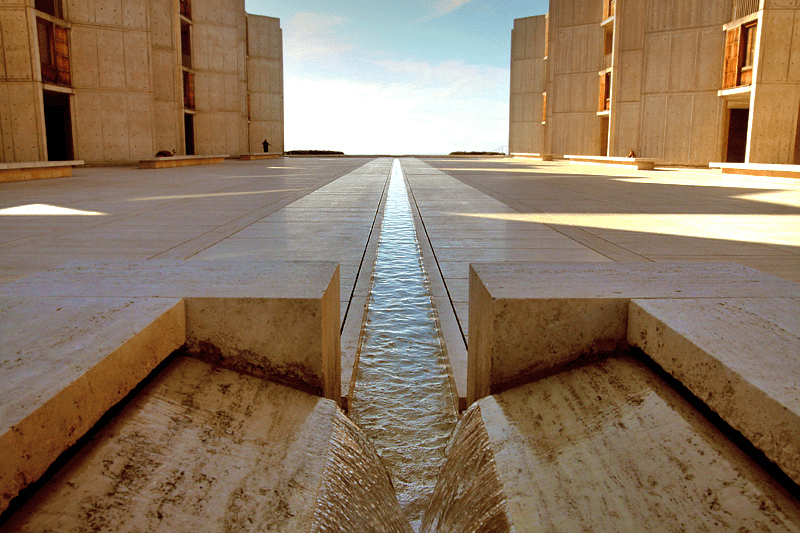

Their first stop: the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California, designed by Louis Kahn (1959–64). The Salk Institute is not only a modernist icon—it also houses the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture (ANFA) and remains a key reference in the field.

What stood out at the Salk Institute? Open-plan layouts, an abundance of natural light, framed views of nature, writeable walls for notes and ideas, and informal meeting areas where scientists could connect and exchange thoughts. These features had been personally requested by Jonas Salk, who believed—through direct experience—that they promoted wellbeing and mental performance.

Laboratories That Foster Collaboration

At the Centre for Neural Circuits and Behaviour (University of San Diego), the team observed labs connected to outdoor terraces where scientists could socialise, nap in hammocks, or hold informal gatherings. At Genentech Hall (UCSF, Mission Bay), labs were grouped around shared offices and a café-kitchen that served as a hub for spontaneous meetings and collaboration.

In contrast, at Harvard, the team found that newly renovated labs placed offices on the opposite side of the building, separating Principal Investigators (PIs) from lab staff. This spatial division created a psychological barrier that weakened communication. At Columbia University, Nobel Laureate Professor Richard Axel told Ritchie that lab work often becomes repetitive and isolating—making informal conversations vital for generating new ideas.

The Dangers of Disconnection

The conclusion was clear: physical separation in the workplace can undermine scientific creativity. Informal interactions, visual connection, and shared spaces were not just “nice to have”—they were essential for collaborative breakthroughs.

Returning to London, the team visited both UCL’s experimental labs and the Gatsby Unit’s theoretical spaces, noting spatial and technical requirements. However, the most valuable insights came from conversations with PhD and postdoctoral students. Across the board, they emphasised that social interaction was key to sustaining innovation.

The interaction between theoretical and experimental scientists, from many countries and with a wide range of specialities and knowledge, is considered key to fostering collaborations that can create the next breakthrough in neuroscience.

Architect Ian Ritchie

Right: Light-filled corridor with blue upholstered seating designed to encourage spontaneous social interaction and moments of rest.

From Dialogue to Design

In 2010, the team launched a series of monthly workshops that brought together architects, neuroscientists, engineers, and project administrators. These sessions allowed both groups to learn from each other—architects understanding lab workflows, scientists understanding the impact of spatial choices.

Rather than following a top-down process, the final design emerged from dialogue, curiosity, and interdisciplinary respect. The result: a building that does more than house science—it facilitates it.

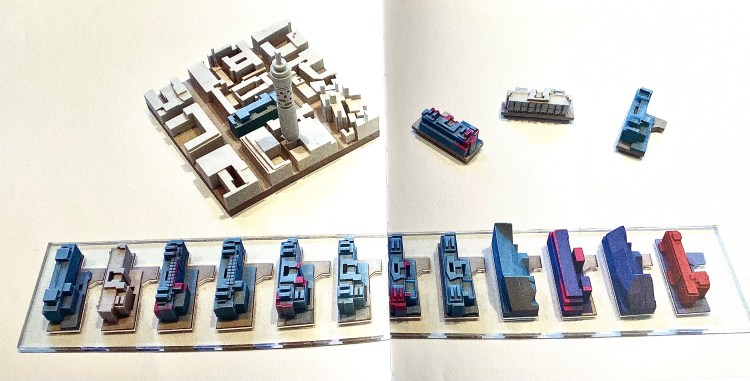

After each meeting between the architects and scientists, a new model was produced to reflect their discussions—serving as a tactile conversation tool for the next workshop and ensuring the design remained grounded in collaborative insight.

This case is a model for interdisciplinary innovation in architecture. As the field of neuroarchitecture grows, the lessons from the SWC remain foundational—inviting us to imagine what other human-centred spaces might emerge when we truly design with the brain in mind.

Looking Ahead

The Sainsbury Wellcome Centre exemplifies what is possible when architecture truly listens to neuroscience. It proves that form can follow function, and that spaces built with the brain in mind can foster not just productivity, but purpose.

In the next article, we will explore how a series of interdisciplinary workshops shaped the architectural features of the SWC—revealing how the dialogue between architects and scientists translated into design decisions that support research, interaction, and wellbeing.

The Sainsbury Wellcome Centre reminds us that the future of design lies not just in how spaces look—but in how they help us think, connect, and create.

References

Allen, T. J., & Henn, G. W. (2007). The organization and architecture of innovation: Managing the flow of technology. Routledge.

Eberhard, J. P. (2009). Brain landscape: The coexistence of neuroscience and architecture. Oxford University Press.

Ferry, G. (2017). Neural architects: The Sainsbury Wellcome Centre from idea to reality. Unicorn Publishing Group LLP.

Sailer, K., & Thomas, M. (2019). Research environments: the spatial configuration of research buildings. Building Research & Information, 47(2), 146–167.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2017.1356122

Sternberg, E. M. (2009). Healing spaces: The science of place and well-being. Harvard University Press.

Ritchie, I. (Ed.). (2020). Neuroarchitecture: Designing with the mind in mind (Architectural Design). Wiley.

3 thoughts on “Designing with the Brain in Mind: Lessons from the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre”