The skin is the largest sensory organ of the human body and the first to form during embryonic development. Before opening our eyes or hearing a voice, we can already feel. Every texture, temperature variation, or pressure activates thousands of receptors distributed across the body’s surface; and through them, the skin communicates directly with the nervous system.

That is why, when a musical piece moves us, when an architectural work overwhelms us, or when a memory touches us deeply, the body responds with an ancient and spontaneous gesture: goosebumps.

This piloerection is the result of a deep emotional circuit: the amygdala is activated, the autonomic nervous system responds, and the tiny muscles around each hair follicle contract.

It is an involuntary reaction, an evolutionary echo that demonstrates that what we perceive—whether light, sound, or touch—has reached the emotional core of the brain. And in architecture, this truth reveals something essential: spaces are not just inhabited. Spaces are felt.

The Neuroscience of Touch: From Material to Emotion

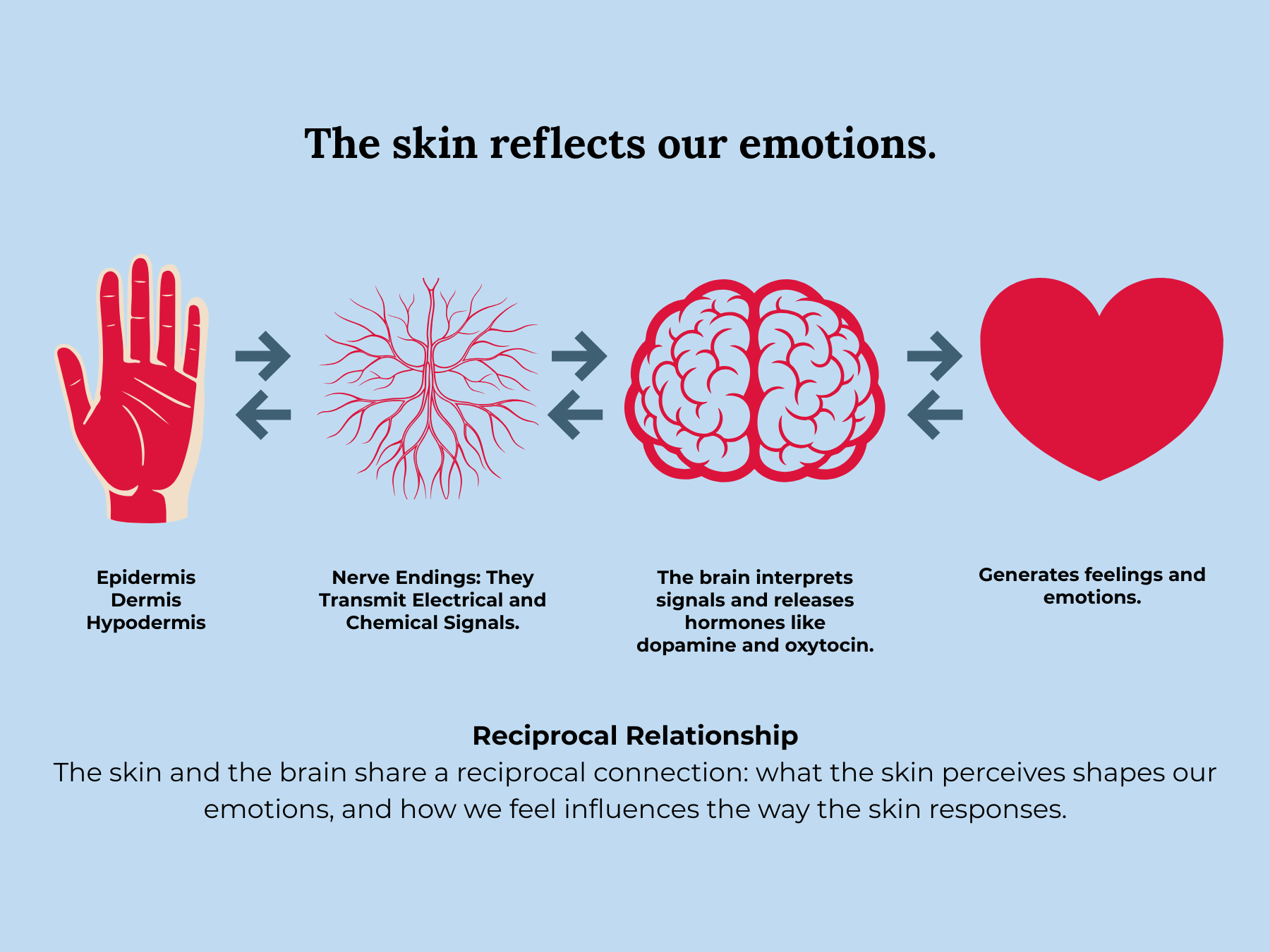

Every everyday gesture — stepping onto the floor in the morning, resting a hand on a table, sinking into a sofa — activates specialised receptors that send information to the brain in milliseconds. But the information does not remain in the sensory cortex: it also reaches the limbic system, where emotions, memory and internal safety are processed.

This is why touch is a silent emotional language.

Every material, every temperature, every texture shapes how we feel in a space.

The Pathway of Touch

Tactile receptors detect four major stimuli: pressure, texture, vibration and temperature. Based on that signal, the brain interprets the environment as warm, cold, welcoming, hostile, soft, rough or distant — nearly always without our conscious awareness.

Textures: The Silent Story of Materials

Textures communicate as much as colour, form, or light. They are the first point of contact between the body and the space.

- Rough, plastic, or cold textures

Trigger micro-alerts.

The brain interprets them as stimuli that require caution, generating a subtle but sustained vigilance. Over time, this kind of environment drains emotional energy, contributing to sensory fatigue and disconnection.

- Soft, warm or natural textures

Wool, cotton, linen, untreated wood, plant fibres…

These materials activate tactile pathways linked to comfort, care and early experiences of affection.

They help us lower our guard, breathe differently and feel received by the space.

In neuroarchitecture, texture is not decoration — it is emotional regulation.

Touch regulates emotional safety, physical comfort and the quality of rest.

Temperature: The Emotional Climate of a Space

The skin registers temperature long before the mind forms the thought “I’m cold.” Thermal receptors alert the brain to heat, cold, drafts and humidity, adjusting our emotional state before we are aware of it.

- Moderate warmth

Creates calm, security, and connection.

This tranquillity leads to stronger relationships and encourages open communication. By nurturing these connections, one builds a supportive environment that boosts resilience and well-being.

- Excessive cold

Triggers muscular tension, reduces cognitive performance, and keeps the body on alert as it tries to conserve heat.

This has direct implications for design:

- Resting areas need materials with warm thermal perception (wood, textiles, natural fibres).

- Cold materials (metal, polished marble, stone) should be avoided in surfaces meant for prolonged contact.

Heat extremes also disrupt brain function — reducing clarity and increasing irritability — while low sunlight diminishes serotonin and melatonin, affecting mood and sleep.

Thermoperception is emotional architecture.

“The eye isolates, while the other senses unite; they integrate the self with the world.”

Juhani Pallasmaa

The Skin as an Emotional Mirror

Goosebumps — one of our most fascinating reflexes — are emotional architecture in its purest form. A space elicits them when it activates a memory, an emotion or a deep sense of beauty.

The chain is simple:

Intense emotion → amygdala → autonomic nervous system → follicular muscles → hair rising.

But its meaning reaches further: goosebumps reveal that the body recognises significance, awe or emotional truth before the mind finds the words.

Juhani Pallasmaa: Designing with the Skin in Mind

In The Eyes of the Skin, Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa criticises the dominance of vision in modern architecture and advocates for a multisensory approach. The “ocularcentrism” of contemporary design privileges what is seen over, what is lived.

Neuroarchitecture reinforces this critique with three propositions:

1. Avoiding Tactile Sterility

A space full of cold, smooth, homogeneous surfaces may be visually impeccable — and emotionally barren.

2. Choosing Materials for Their Emotional Temperature

Every material has a tactile language:

- Warm wood — calming

- Cold metal — distancing

- Smooth stone — grounding

- Textiles — comforting

3. Design for the whole body, not just the eyes

We truly experience a space when we walk barefoot, grasp a handrail, sit, recline or touch a textile.

What the skin interprets, the mind converts into emotion.

In summary: The skin as a bridge between body, emotion, and space

Touch shapes our emotional safety, physical comfort and quality of rest. It is a primary form of communication — a bridge between the body and the world. Through the skin, our largest sensory organ, we perceive textures, temperatures and pressures that directly influence our emotional state. A simple embrace can ease tension and restore connection.

When design respects the physiology of touch, a space stops being merely functional: it becomes a refuge. Soft textiles, warm materials and thoughtful spatial composition create environments that soothe and sustain us. The skin recognises these cues immediately and responds with calm.

Integrating touch into design means creating places that protect, restore and return to the body a profound sense of safety.

This is how home becomes an emotionally sustainable space — where everyday life feels like a practice of care.

Design with the skin in mind.

Referencias

Pallasmaa, J. (2005). The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. John Wiley & Sons.

Tyson, G. A. (2021). Environmental psychology and architecture: The hidden dialogue. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 73, 101550.

Arbib, M. A. (Ed.). (2016). From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Architecture of Brain–Environment Interaction. MIT Press.

McGlone, F., Wessberg, J., & Olausson, H. (2014). Discriminative and affective touch: Sensing and feeling. Neuron, 82(4), 737–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.001