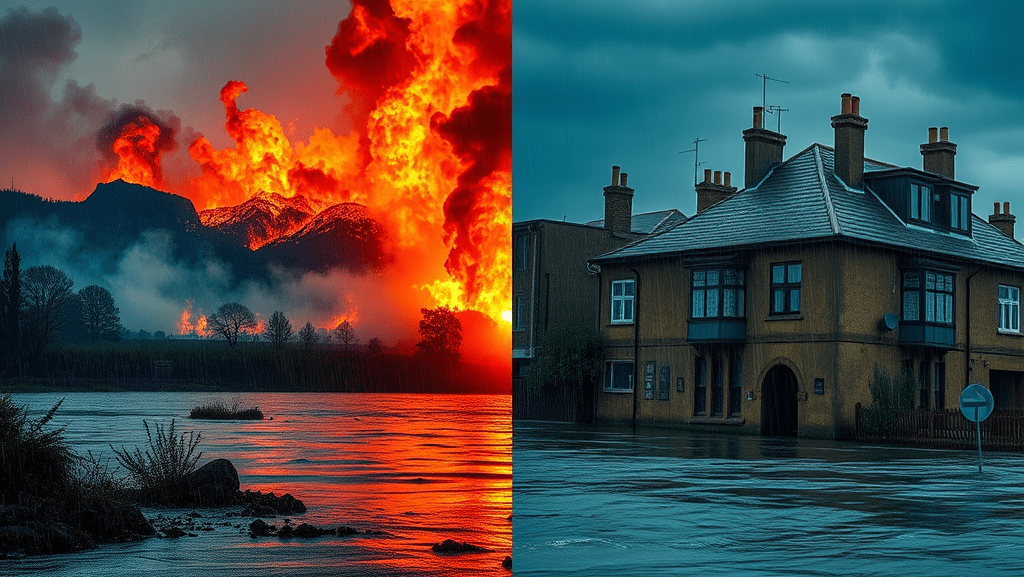

Climate no longer appears as a seasonal variation, but as a convergence of simultaneous extremes. While the Southern Hemisphere burns —with devastating wildfires in Chile and across large areas of Patagonia in Argentina— the Global North and parts of Africa face persistent flooding, from the United Kingdom to Mozambique. Fire and water coexist in the same present, tracing a map that no longer shocks, but steadily wears us down.

These are not isolated events. They are the diagnostic image of a planet in transformation, reshaping not only landscapes and cities, but also the way we inhabit space and experience safety. When the environment becomes unpredictable, the body registers it. And this leads to an unavoidable question:

what happens to our mental health when the world no longer offers stability?

The Water Threat

Increasingly intense storms have led to evacuations, repeated service disruptions and recurring material losses. Flooding is no longer an isolated event; it returns. And with repetition, the relationship with inhabited space changes.

Rain ceases to be a passing condition and becomes an anticipated threat: sleep is disrupted, vigilance increases, and domestic calm erodes.

The problem is not only the water, but the constant uncertainty it creates. The home —and the infrastructure that surrounds it— should act as a filter between the external world and the body. When that system fails, the nervous system remains on alert.

How long does a territory need to become habitable again?

The Threat of Fire

In contrast, in the southern part of the continent —particularly in Chile and Argentina— risk takes a different form: widespread fire. Wildfires do not only damage buildings or infrastructure; they threaten all forms of life. They devastate farms, livestock, and crops; destroy entire habitats; displace and kill wildlife; and damage the fertile topsoil, undermining the territory’s capacity to regenerate for years — even decades.

Although fire does not always reach buildings directly, it disrupts the systems that sustain life: air becomes unbreathable, visibility fades, water is contaminated, and everyday rhythms are destabilised. Where water overwhelms infrastructure and erases physical boundaries, fire invades the invisible. In both cases, the message is clear: when territory is compromised, no system —urban, social or emotional— remains untouched.

After high-intensity fires, soils can remain ecologically degraded for decades; regenerating 1 cm of fertile soil can take between 100 and 400 years.

Climate Anxiety: A Rational Response

Climate anxiety is not a trend, nor a generational exaggeration. It is a coherent response to an environment perceived as unstable. It is not only about fear of the future, but about living in constant anticipation: of the next storm, the next wildfire, the next displacement.

When the built environment does not allow the body to lower its guard, anxiety ceases to be episodic and becomes chronic. The body does not distinguish between environmental threat and existential threat; both activate the same stress mechanisms.

Urbanism, architecture, and exposure to risk

This situation is not accidental. Urban development and architecture have amplified exposure to risk through impermeable surfaces, construction on floodplains, expansion into the wild land–urban interface, and outdated drainage systems. For decades, these impacts disproportionately affected working-class neighbourhoods. Today, that boundary has become blurred.

Affluent areas in cities such as Bogotá are beginning to experience flooding and landslides; in regions like California, wildfires have destroyed entire neighbourhoods of high-value housing. Climate change no longer clearly distinguishes between social classes. What remains profoundly unequal is the capacity to recover.

Construction and climate: confronting responsibility

At a global scale, the built environment accounts for a significant portion of energy-related emissions:

| Impact category | Share of emissions / impact | Key processes and causes | Climatic consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embodied carbon (construction phase) | ≈ 11%–13% of global energy-related emissions | Cement, steel and glass production; transport of materials and heavy machinery | High emissions before occupation; degradation of quarries and natural resources |

| Operational emissions (building use) | ≈ 27%–28% | Heating, cooling, lighting and domestic hot water | Increased energy demand in buildings poorly adapted to thermal extremes |

| Land-use change | Not directly quantified within the sector | Soil sealing with asphalt and concrete; urban expansion into forests and natural areas | Increased flooding risk, reduced soil absorption and urban heat-island effect |

| Waste management | ≈ 30%–40% of global waste | Construction and demolition waste | Landfill saturation and loss of potentially reusable materials |

The climatic impact of the built environment extends beyond operational energy use to encompass the material, spatial and temporal decisions embedded in its production.

While mitigation strategies are being implemented, their pace remains misaligned with the urgency of the climate crisis. The challenge is not solely technical, but temporal.

From mitigation to mental health

Here a less discussed dimension emerges: delays in climate action also carry a psychological cost. Living in environments that fail to provide protection against climatic extremes erodes the sense of control, safety and belonging.

Architecture and urbanism do not merely shape spaces; they shape emotional conditions. Designing without considering climatic impact is not only an environmental failure — it is a way of producing mental vulnerability, with direct consequences for productivity, economic stability and social cohesion.

Inhabiting an unstable world

Regeneration exists, but it unfolds on a timescale different from the human one.

The greatest risk we face is not only climatic, but the normalisation of the absence of refuge. The framework through which we think about housing and infrastructure must be fundamentally reconsidered: restoring to the body the possibility of feeling safe in a changing and threatening world.

Because when even the home —and the systems that sustain it— fails to protect, the crisis ceases to be environmental and becomes intimate. This shift in perspective compels us to reimagine architecture not merely as shelter from the climate, but as support for mental health, social stability and everyday life.

Recommended Readings

- American Psychological Association (2017). Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications, and Guidance.

- World Health Organization (2022). Climate change and health.

- Nature Climate Change (2021). Climate anxiety in young people: a global survey.

- UN Environment Programme & GlobalABC (2023). Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction.

- Newman, P., Beatley, T., & Boyer, H. (2017). Resilient Cities. Island Press.