Have you ever felt uneasy walking down a long corridor or turning into a quiet alleyway? Have you ever felt uplifted when opening a window to a view of the sea or the mountains? Have you ever felt small standing before a towering skyscraper? In cinema, the choice of styles, design, and architecture is never random. Everything is carefully considered because space is a vital part of storytelling—a silent yet powerful character that shapes our emotions.

“I think of the set as a living organism. It should reflect the mood and inner life of the characters.”

Guillermo del Toro — Film director

A well-designed set doesn’t just look realistic—it feels emotionally right. Whether it’s a small flat or a monumental dystopian city, every detail is intentional and symbolic. Production designers work closely with directors and cinematographers to ensure that each space deepens the narrative and reflects the characters’ inner worlds. What set designers achieve intuitively, neuroarchitects explore through science.

Filmmakers understand something architects sometimes overlook: space speaks. It influences how we move, feel, think, and relate to others. Through lighting, proportion, material, and rhythm, movies offer condensed emotional experiences that mirror what neuroarchitecture seeks to achieve in the built environment.

So, what happens when we study buildings the way we analyse film? What if our cities, homes, and schools were designed with the same emotional precision as a movie scene? In this article, we’ll explore how seven iconic films use architecture to create powerful emotional effects—and what designers can learn from them.

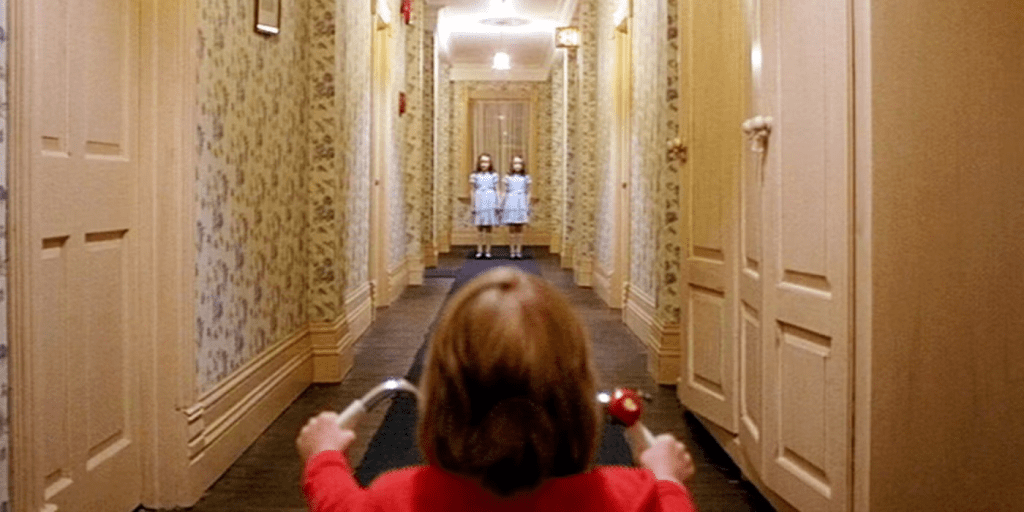

Fear – The Shining (1980)

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining is one of the most iconic examples of how space can generate psychological terror. The Overlook Hotel is not just a haunted building—it’s a labyrinth of dread. Its overwhelming symmetry, sterile corridors, and shifting spatial logic create a sense of isolation and disorientation.

Long tracking shots and impossible architecture (like windows that don’t connect to outside walls) add to the unsettling effect. Viewers feel lost alongside the characters, trapped in a space that seems to grow colder and more menacing with every frame. Kubrick uses architecture as a psychological weapon, showing how design can evoke anxiety even without visible danger.

In neuroarchitecture, we know that spatial unpredictability and lack of visual cues can trigger stress. The Shining magnifies this principle, turning disorientation into horror.

Joy – Amélie (2001)

Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Amélie transforms everyday Paris into a whimsical world of wonder. The architecture in the film—cosy flats, intimate cafés, and vibrant street corners—is layered with warmth, colour, and character. Every detail contributes to a sense of emotional safety and delight.

The protagonist’s flat, with its deep reds, soft lighting, and eclectic decor, mirrors her inner life: imaginative, playful, and quietly hopeful. The scale of the spaces is human and approachable—nothing feels overwhelming or sterile. Instead, the environment invites curiosity, reflection, and joy.

This is emotional design at its best. The film shows how colour, texture, and proportion can create spaces that feel emotionally nourishing. In neuroarchitecture, we mention environments that reduce stress and increase dopamine. Amélie does this visually—demonstrating that joy can be built, not just felt.

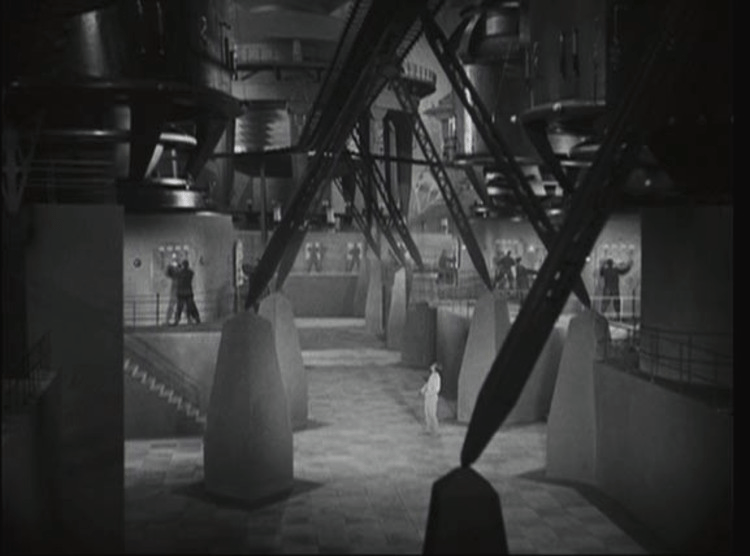

Oppression – Metropolis (1927)

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis is a landmark in cinematic architecture—one that portrays the emotional weight of social inequality through monumental design. The upper city is futuristic, soaring, and mechanical, while the underground workers’ quarters are dark, cramped, and dehumanising. Architecture in this film is not neutral—it’s a clear expression of control and submission.

The overwhelming scale of the towers dwarfs the human figure, reinforcing the idea that individuals are insignificant within the system. Rigid symmetry and mechanical movement reflect a world stripped of empathy. In contrast, the workers’ world is enclosed, repetitive, and suffocating—its design mirroring the emotional fatigue of oppression.

Metropolis shows how spatial hierarchy and contrast can visualise power structures. In neuroarchitecture, these ideas matter when we consider how environments can either empower or suppress people’s sense of agency. The film is a stark reminder that design always communicates—even when it’s silent.

Class Tension – High-Rise (2015)

Ben Wheatley’s High-Rise, based on J.G. Ballard’s novel, is a brutal allegory of social collapse contained within a single building. The architecture itself is the story: a modernist high-rise where each floor reflects a different social class—wealth and privilege at the top, poverty, and instability below.

The building’s design, with its concrete austerity and isolating verticality, becomes a pressure cooker. As infrastructure breaks down and community erodes, the spatial order collapses into chaos. Lifts fail, light disappears, and once-sterile interiors are reduced to primitive battlegrounds.

High-Rise uses architecture to critique the illusion of control and the fragility of social order. In neuroarchitecture, verticality and social separation can translate into real emotional experiences—feelings of exclusion, dominance, or despair. The film visualises how spatial segregation can lead to psychological disintegration.

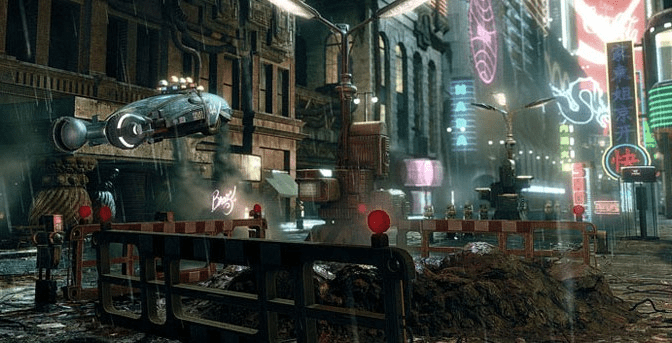

Melancholy – Blade Runner (1982)

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner paints a haunting picture of the future—one dominated by verticality, rain, shadows, and synthetic light. The city is dense, overwhelming, and constantly in motion, yet emotionally hollow. It’s a space of profound melancholy and alienation.

The architecture blends brutalism, retrofuturism, and decay. Massive concrete buildings loom over neon-lit streets, while the interiors feel cold, impersonal, and transient. Even the luxurious spaces are dark and sterile, disconnected from warmth or comfort. It’s a world designed for machines, not people.

Emotionally, Blade Runner evokes a quiet sadness—of longing for connection in a place built to erase identity. In neuroarchitecture, this reflects the impact of overstimulation, lack of natural elements, and sensory imbalance on mental wellbeing. The film reminds us that even the most technologically advanced environments can leave the human spirit behind.

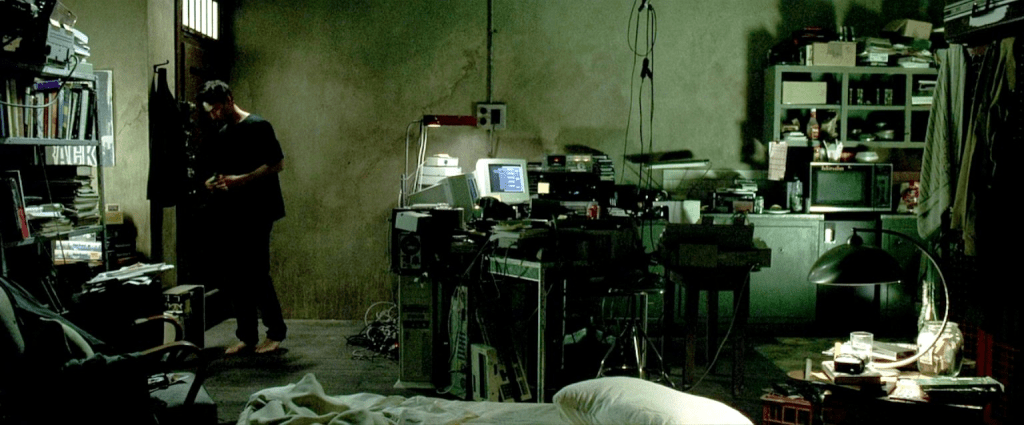

Control and Liberation – The Matrix (1999)

In The Matrix, architecture becomes a metaphor for illusion and control. The simulated world is built on rigid grids, endless office corridors, and monotonous interiors—spaces designed to suppress individuality and reinforce obedience. Everything is orderly, angular, and artificial.

But as Neo awakens, architecture begins to shift. Abandoned buildings, raw industrial spaces, and open landscapes break the illusion of control. These “real world” spaces may be rough, but they offer freedom, possibility, and truth.

The Matrix uses architecture to symbolise the journey from confinement to liberation. In neuroarchitecture, this resonates with how spatial design can either constrain or expand perception. Clear lines, repetitive layouts, and cold materials can create mental fatigue—while open, organic spaces support cognitive flexibility and emotional resilience.

Lessons for Real-World Design

What do these films teach us about architecture beyond the screen?

Each cinematic space we’ve explored transforms emotion into form. Fear, joy, oppression, melancholy, control, liberation, chaos—these aren’t just feelings; they’re spatial experiences. Through lighting, proportion, rhythm, texture, and material, filmmakers construct emotional landscapes. And architects can do the same.

Neuroarchitecture provides the scientific grounding for this. It studies how the brain and body respond to space—how overstimulation triggers anxiety, how warm textures increase trust, how certain spatial rhythms support cognitive clarity.

By learning from film, designers can sharpen their emotional awareness. How will a child feel entering this classroom? What does a hospital corridor communicate to someone distressed? Does a public square invite joy—or isolation?

Cinematic spaces invite us to think like storytellers. To design not only for function, but for feeling.

Final thoughts

Films remind us that space speaks—even when no one is talking. Architecture has the power to move us, to unsettle us, to make us feel safe, or to amplify our inner worlds. Every hallway, every window, every shadowed corner carries emotional weight.

As designers, we can learn from the way filmmakers choreograph space to tell stories. We can ask: What does this room feel like? What kind of inner world does this building invite? When we design with the brain—and the heart—in mind, architecture becomes more than shelter. It becomes an experience.

So next time you step into a space, imagine it as a movie scene. What emotion would it evoke? And what story would it tell?

References

Lights, Camera, Architecture!: Where Set Design and Architecture Cross Over https://www.archdaily.com/910113/lights-camera-architecture-where-set-design-and-architecture-crossover#:~:text=The%20two%20fields%20also%20work,of%20architecture%20and%20built%20environments.

How architecture and set design are blurring the line between city and stage https://www.iconeye.com/design/architecture-set-design-theatre-stage-city

From Screen to Structure: What Architects Can Learn from Cinematic Set Design https://www.druryarchitects.com/post/from-screen-to-structure-what-architects-can-learn-from-cinematic-set-design

A Clockwork Orange | 1971 https://movie-locations.com/movies/c/Clockwork-Orange.php

How Architecture Speaks Through Cinema. https://www.archdaily.com/872754/how-architecture-speaks-through-cinema

20 Great Movies every Architect should watch https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/article/20-great-movies-every-architect-should-watch/

Building Worlds: Movie Recommendations from MoMA’s Department of Architecture and Design https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/263

Architect Movies https://www.imdb.com/list/ls069787262/

ARCHITECTURE + FILM https://architectureandfilm.com/