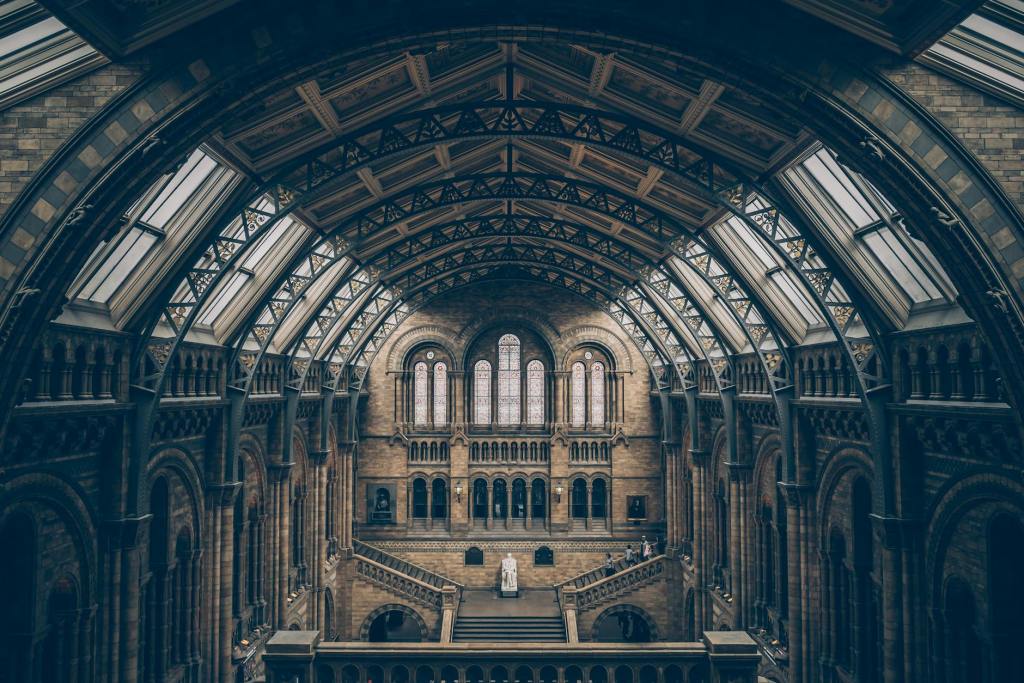

Have you ever noticed that most of the iconic buildings in the world are symmetric?

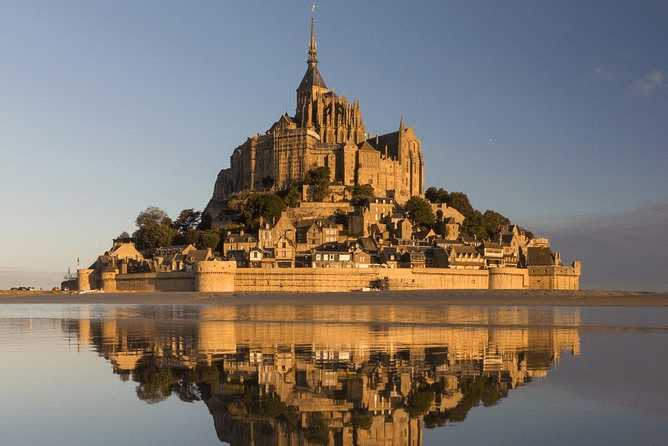

A glance at architectural history reveals a fascinating pattern: symmetry dominates. From ancient temples to neoclassical palaces, some of the most enduring and admired buildings are defined by their balanced proportions and mirrored images.

Across cultures and centuries, symmetry has been revered as a symbol of harmony, health, and even divinity. But as design evolved, something curious emerged: not all people are drawn to symmetry in the same way.

“The design of a temple depends on symmetry, the principles of which must be most carefully observed by the architect.”

Vitruvius. Ten Books on Architecture – Book III, Chapter I.

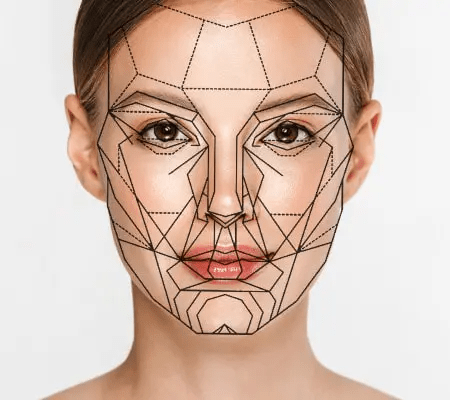

Facial visual analysis methods.

Why Humans Prefer Symmetry

Symmetry is the balanced and proportionate arrangement of elements on either side of a central axis. In design, it frequently means that a building’s left and right sides mirror each other, creating a sense of order, stability, and harmony. But why are we so keen on it?

1. Biological Wiring

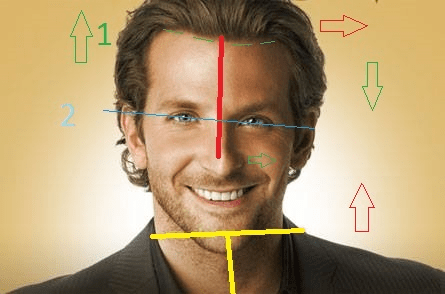

Symmetry is subconsciously associated with health and genetic fitness. In evolutionary biology, symmetrical faces and bodies signal good development and the absence of disease. This link may have wired our brains to prefer symmetrical forms as trustworthy and attractive.

Visual perception research supports this: the human brain processes symmetrical images more quickly and more easily than asymmetrical ones. Symmetry reduces cognitive load and provides a sense of order in a world that can feel unpredictable.

Numerous studies confirm that facial symmetry is a strong component of physical attractiveness. For example, research by Gillian Rhodes and colleagues demonstrated that increasing the symmetry of a face also increased how attractive it was perceived. Conversely, reducing symmetry led to lower attractiveness ratings.

Another foundational study by Karl Grammer and Randy Thornhill found that facial symmetry plays a significant role in human mate selection. They proposed that our preference for symmetry is rooted in biology, as it may serve as a marker of health and genetic fitness.

2. Psychological Comfort

Psychologically, symmetry brings a sense of stability. It implies control, predictability, and familiarity. These traits are emotionally reassuring—especially in times of stress. That’s why many hospitals, temples, and civic buildings rely on symmetrical layouts: to calm, centre, and ground.

This ancient insight still echoes in architectural education today. Symmetry was not just about beauty—it was about logic, order, and human experience.

3. Cultural Ideals

From classical temples to Islamic art, symmetry has often been linked with spiritual perfection. Architectural treatises like Vitruvius’ De Architectura positioned symmetry as essential to good design. The Renaissance revived this belief, aligning mathematical proportions with moral and aesthetic ideals.

But Not Everyone Prefers Symmetry

1. Creative Minds Crave Complexity

Recent studies indicate that creativity is correlated with a preference for complexity and asymmetry. Creative individuals tend to enjoy unpredictability, novelty, and contrast—all of which are frequently absent in strictly symmetrical forms.

A 2019 study by Kharkhurin and Yagolkovskiy found that individuals with high divergent thinking scores—a core measure of creativity—exhibited stronger preferences for complex and asymmetrical visual patterns. This supports the idea that creative cognition thrives on less conventional, less balanced visual input.

2. Neurodivergent Aesthetic Perception

Neurodivergent individuals—particularly those with autism or ADHD—may experience and interpret aesthetic stimuli differently. Some find symmetrical environments monotonous or overstimulating. Others seek irregularity as a form of cognitive stimulation or emotional expression.

A 2024 review in Frontiers in Psychology proposes that neurodiverse populations may exhibit stable, alternative patterns of aesthetic preference, favouring asymmetry and abstraction.

This insight matters. As we aim for more inclusive design, it’s essential to recognise that not all minds feel “at home” in perfectly ordered spaces.

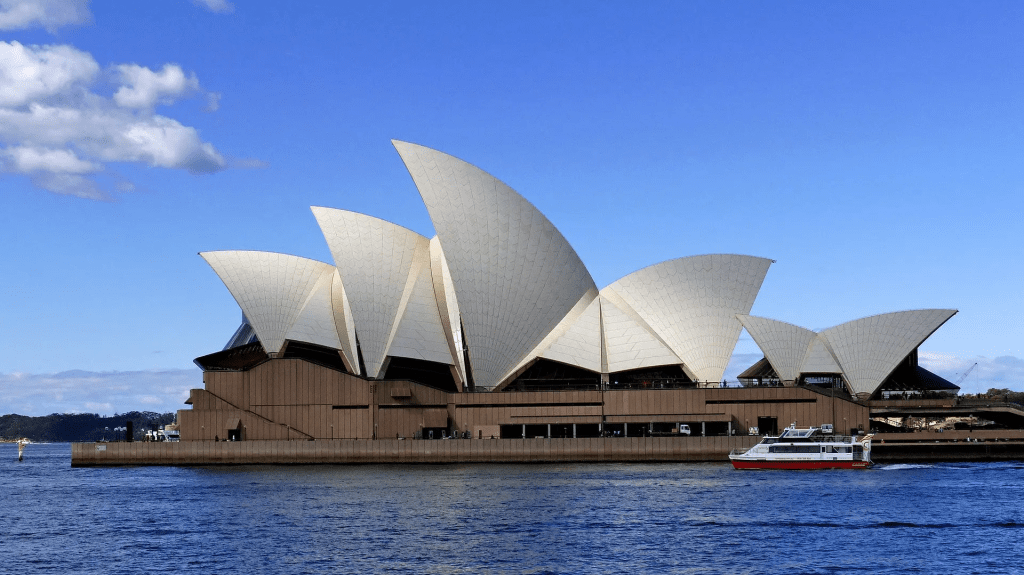

The Role of Asymmetry in Architecture

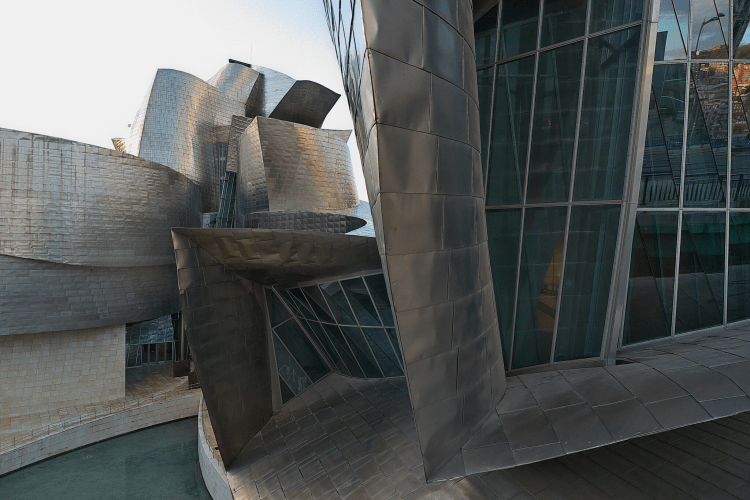

Symmetry once symbolised perfection—but in modern and postmodern architecture, asymmetry is a tool of provocation. Architects like Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, and Daniel Libeskind use imbalance, distortion, and rupture to challenge our senses and spark emotion.

These designs don’t aim to calm—they aim to awaken. To question. To move us beyond the familiar.

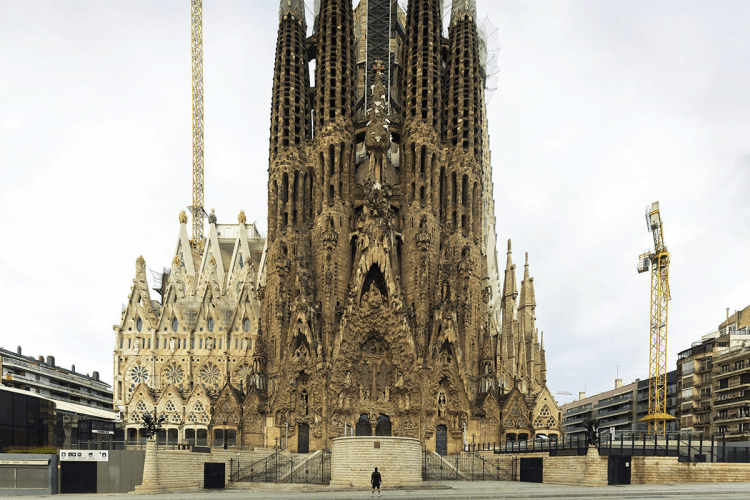

In urban design, too, asymmetry can foster creativity and spontaneity. Think of Gaudí’s Sagrada Família: its irregular forms inspire awe not despite their asymmetry, but because of it.

Rethinking Symmetry in Contemporary Design

Symmetry continues to resonate. It comforts, communicates clarity, and gives structure to our built environments. But asymmetry, when used deliberately, introduces humanity into design. It mimics the organic irregularity of nature, the quirks of personality, the complexity of emotion.

In neuroarchitecture, both play a role. Symmetry might offer sensory calm for some, while asymmetry provides cognitive engagement for others. The challenge—and the opportunity—is to design with both in mind.

This means creating spaces that are not only visually pleasing, but also cognitively and emotionally responsive. A hospital, for instance, might rely on symmetry in patient rooms to promote clarity and reduce stress, while incorporating asymmetrical art installations or textures in communal areas to stimulate curiosity and engagement.

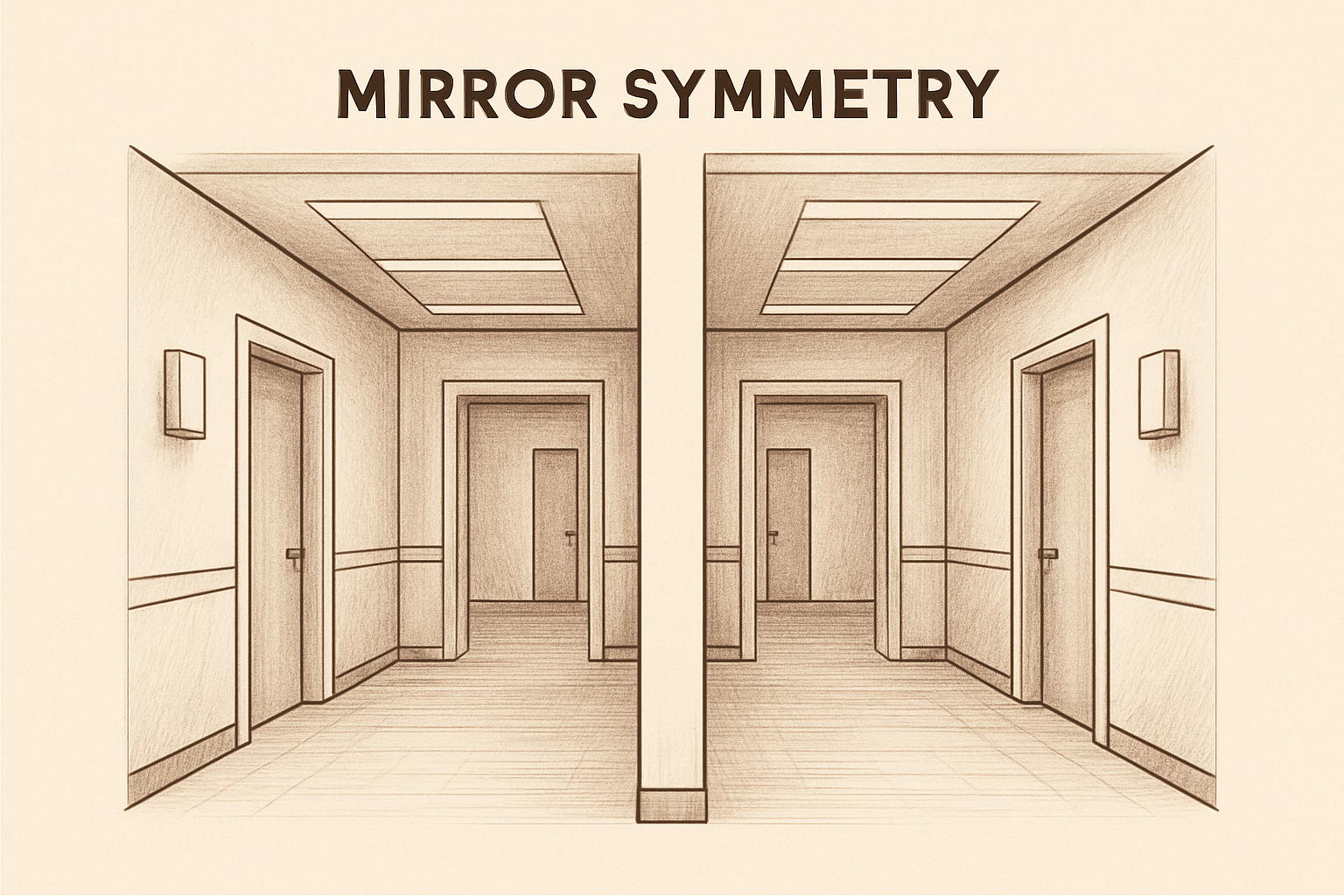

However, while symmetrical façades may feel safe and familiar, overly symmetrical interior layouts can be disorienting—particularly for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease or impaired coordination, who may struggle with spatial awareness, including distinguishing left from right. In such cases, mirrored corridors and identical circulation paths can hinder orientation and increase anxiety.

By embracing this dual approach, designers can craft environments that are flexible, inclusive, and attuned to the full spectrum of human perception. Rather than enforcing uniformity, neuroarchitecture invites us to explore balance in a more nuanced way—where calm and stimulation coexist.

What kinds of symmetry or asymmetry speak to you most? As designers, educators, or simply as users of space, we each have a role in shaping environments that reflect both clarity and complexity.

How will you design for balance?

References

- Kharkhurin, A. V., & Yagolkovskiy, S. R. (2019). Preference for Complexity and Asymmetry Contributes to Elaboration in Divergent Thinking. ResearchGate

- Lyssenko, N., et al. (2024). Aesthetic Processing in Neurodiverse Populations: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Psychology. PubMed

- Hutson, James and Hutson, Piper (2024) “Resonant Perceptions: Exploring Autistic Aesthetics through Embodied Cognition,” Ought: The Journal of Autistic Culture: Vol. 5: Iss. 2, Article 5.

DOI: 10.9707/2833-1508.1162 - Rhodes, G., et al. (1999). Facial Symmetry and the Perception of Beauty. [University of Western Australia]

- Grammer, K., & Thornhill, R. (1994). Human (Homo sapiens) facial attractiveness and sexual selection: The role of symmetry and averageness. Journal of Comparative Psychology.

- Grammer, Karl & Fink, Bernhard & Moller, Anders & Thornhill, Randy. (2003). Darwinian aesthetics: Sexual selection and the biology of beauty. Biological Reviews. 78. 385-407.

- Resonant Perceptions: Exploring Autistic Aesthetics through Embodied Cognition https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1162&context=ought

One thought on “Symmetry vs. Asymmetry in Design”