1. A Moment by the Water

We are made mostly of water. It flows through our veins, cushions our brain, and fills the cells that sustain life. But our connection to it runs deeper than physiology. Water is something we feel. Its shimmer, its rhythm, its quiet persistence—these things speak to something ancient within us. Water is memory, movement, and a mirror. It soothes not only because we depend on it, but because we recognise it.

At La Alhambra in Granada, the sound of running water weaves through the courtyards like a soft lullaby. A tranquil murmur dances off ancient stone, catching glints of sunlight as it moves. Sitting by the fountain, the breath slows. Shoulders release. Something shifts. The same thing happens by the sea: the hush of waves, the vastness of blue, the rhythm of the tide—all of it invites surrender.

Why is this so universal? Why does the mere presence of water bring calm? Is it survival memory, ancestral instinct—or something even deeper, written into the language of our biology?

2. A Biophilic Instinct

Our relationship with water is ancient. From the earliest days of human civilisation, we have settled near rivers, lakes, and coastlines—not only for sustenance but for safety and orientation. The concept of biophilia, popularised by E.O. Wilson, explains this attraction: humans are wired to seek connection with the natural world.

In environmental psychology, theories such as the Savanna Hypothesis and prospect-refuge theory suggest that humans feel most at ease in environments that combine shelter with openness and a view of water. Water is not just a resource—it is a visual and emotional anchor.

Some of the world’s most iconic places aren’t built—they drift, crash, and rise. Glaciers carving valleys, waves shaping shores, springs breathing life into the land. Earth’s most beloved landscapes are sculpted not by hands, but by flow.

3. The Neuroscience of Calm

When we experience the presence of water—especially moving water—our brain responds in ways that support relaxation and regulation.

- Auditory effects: The low-frequency, non-threatening sounds of water engage our parasympathetic nervous system. This is the body’s rest-and-digest mode, counteracting stress responses like rapid heartbeat or shallow breathing.

- Brain wave synchrony: Flowing water triggers alpha waves in the brain, which are associated with wakeful calm and meditative states.

- Neurochemical changes: Studies have shown that being near water reduces cortisol levels while increasing dopamine and serotonin—neurotransmitters linked to pleasure and emotional balance.

Marine biologist Wallace J. Nichols coined the term Blue Mind to describe this phenomenon: a mildly meditative state triggered by contact with water.

“People can experience the benefits of the water whether they’re near the ocean, a lake, river, swimming pool or even listening to the soothing sound of a fountain.”

Wallace J. Nichols — The Blue Mind

4. More Than Sound: A Multisensory Effect

The calming power of water isn’t limited to its sound. It is a full sensory experience:

- Visual: The glimmer of sunlight on rippling surfaces produces dynamic but non-threatening stimuli. This subtle movement is visually engaging without demanding cognitive effort.

- Tactile and thermal: The cooling effects of water or its evaporation can make spaces feel more breathable and comfortable.

- Olfactory: In outdoor settings, water often enhances the presence of natural scents like earth, plants, or rain.

In sensory design, particularly for neurodivergent users, these regulated stimuli can reduce overload and support self-regulation. For some autistic individuals or those with ADHD, water features serve as grounding tools, offering rhythm, predictability, and calm.

This Baroque fountain, topped by Neptune and sea creatures, was built to provide water to the city. Today, is one of the world’s most famous fountains.

It is one of the most beautiful in Japan with its sculpted pines, koi-filled ponds, and artfully framed views. Rooted in centuries of Japanese design, it invites you to wander slowly and see with stillness.

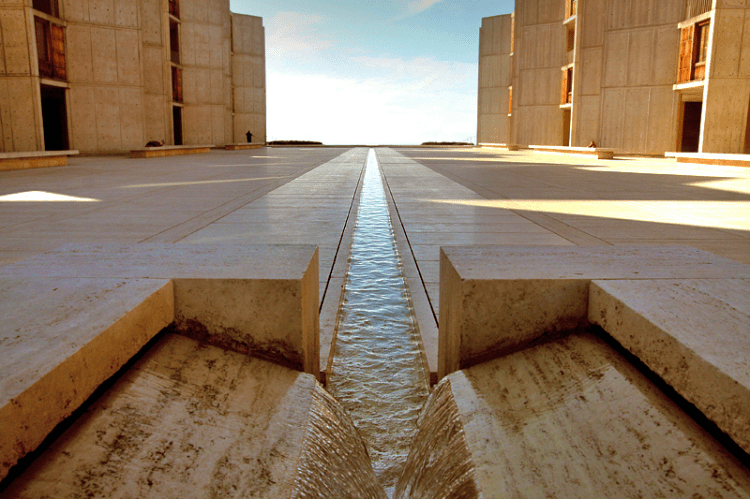

A tranquil composition of stone and sky, where a narrow water channel flows gently between austere concrete forms. This minimalist courtyard, echoing the spirit of Islamic gardens, invites stillness, contemplation, and the quiet rhythm of thought.

5. Water in Design: Practical Applications

Designers across cultures and centuries have instinctively integrated water into their architecture:

- Islamic architecture: Courtyards with fountains in Al-Andalus or Persian gardens use water to symbolise paradise and provide microclimate cooling.

- Japanese Zen gardens: Though often dry, these mimic the flow of water through patterns and gravel, inviting contemplation.

- Contemporary design: From reflective pools in memorials to cascading water walls in hospital lobbies, water brings stillness to complex emotional environments.

Water features can also act as spatial anchors—helping with wayfinding, offering moments of pause, and creating sensory thresholds between zones.

6. A Symbol Across Cultures

Beyond its sensory effects, water holds symbolic power:

- Cleansing: Ritual baths, ablutions, and fountains as sites of renewal.

- Memory: The pools at the 9/11 Memorial invite reflection, grief, and presence.

- Spiritual resonance: In Hinduism, Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism, water plays a central ritualistic role.

These associations deepen our emotional response to water features, even when the design is minimalist.

7. When Water Goes Wrong

Not all water features calm. Poorly designed elements can overwhelm:

- Loud jets in enclosed areas may echo or create sensory stress.

- Overuse of polished surfaces around water increases fall risk.

- Individuals with trauma may find rushing water triggering rather than calming.

Design must be context-sensitive. Scale, sound, rhythm, and access must be tailored to the needs of users and setting.

8. Design Guidelines: Flow, Not Force

To harness the full benefits of water in architecture, consider:

- Human scale: Keep features approachable, not monumental.

- Gentle rhythm: Prioritise flow over pressure.

- Material pairing: Combine water with natural textures (stone, wood, plants).

- Purposeful placement: Use water to invite reflection in courtyards, entrances, or waiting spaces.

In neuroinclusive design, consider quiet water walls, low fountains, or even symbolic patterns that recall water’s movement without using it literally.

Integrating Water into the Heart of Design

Water is more than a material—it is a medium of emotion, memory, and rhythm. When thoughtfully integrated into architecture, it transforms static environments into living experiences. Whether through the shimmer of a courtyard fountain, the hush of an indoor stream, or the symbolic depth of a reflecting pool, water invites connection—not just to nature, but to ourselves.

Design should include water not merely as plumbing, but as a holistic element: something to be harvested, conserved, and celebrated. From rain collection systems to sensory fountains, water can serve both ecological and emotional needs. By placing it at the heart of our spaces, we create environments that breathe, listen, and heal—places where flow becomes feeling, and function becomes poetry.

What might change if we treated water not just as a utility, but as a companion in design?

References

Mental Health Foundation. (2021). Mental Health and Nature: How connecting with nature benefits our mental health. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/explore-mental-health/publications/nature-how-connecting-nature-benefits-our-mental-health

Dzhambov, A. M., Dimitrova, D. D., & Dimitrakova, E. D. (2014). Urban green spaces’ effectiveness as a psychological buffer for the negative health impact of noise pollution: A systematic review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 13(4), 800–812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2014.08.002

Felsten, G. (2009). Where to take a study break on the college campus: An attention restoration theory perspective. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(1), 160–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.11.006

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Nichols, W. J. (2014). Blue mind: The surprising science that shows how being near, in, on, or under water can make you happier, healthier, more connected, and better at what you do. Little, Brown Spark.

Ulrich, R. S. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224(4647), 420–421. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6143402

White, M. P., Pahl, S., Wheeler, B. W., Fleming, L. E. F., & Depledge, M. H. (2017). The “Blue Gym”: What can blue space do for you and what can you do for blue space? Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 96(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315416000332

Wilson, E. O. (1984). Biophilia. Harvard University Press.