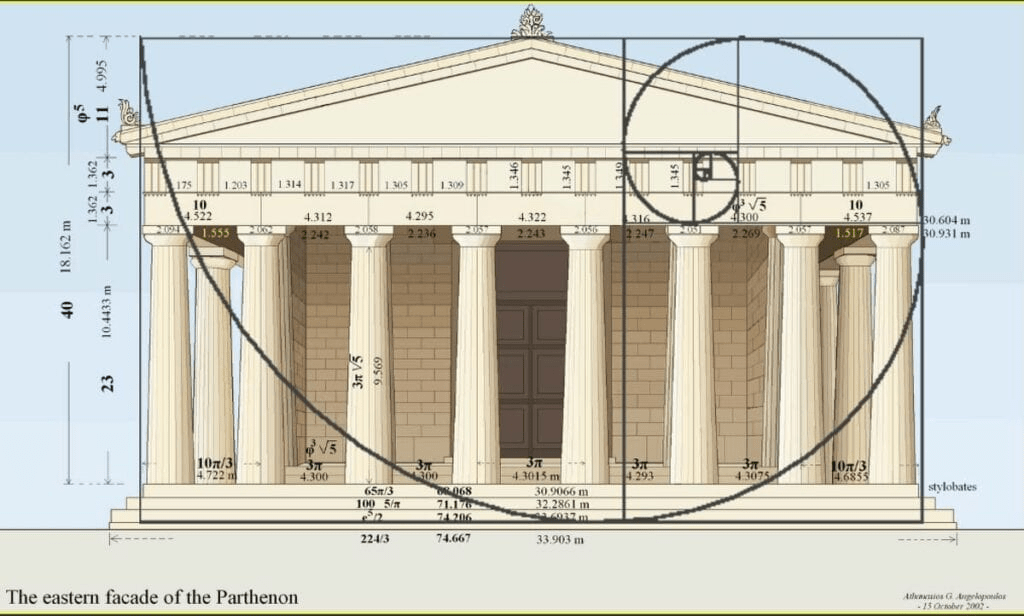

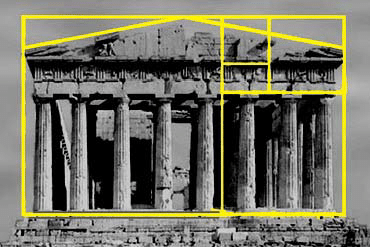

The Parthenon in Athens is often hailed as one of the most beautiful buildings in the world. Dedicated to the goddess Athena, this octastyle Doric temple—built in gleaming Pentelic marble—continues to captivate despite the passage of nearly 2,500 years. But what exactly makes it a masterpiece? Why does its form still resonate with us today?

That question stayed with me until I began exploring the idea of proportion. The more I studied it, the more the Parthenon revealed its quiet brilliance. Its influence has rippled across history—from ancient builders to Renaissance visionaries, and even modern architects like Le Corbusier. There’s something timeless at work here. Could proportion be the key?

The Power of Proportion

Can we measure beauty? Is it a matter of personal taste, or are there patterns our brains are naturally drawn to?

For ancient artists and architects, beauty was not simply a matter of taste—it followed principles. They believed that beauty could be crafted with intention, and one of the most essential tools for achieving it was proportion.

Proportion is the relationship of a part to a whole, or the relative size or amount of one element compared to another. In short, it’s the mathematical and geometric arrangement that creates harmony. This balance can either soothe or unsettle us—depending on how well the elements work together.

This concept plays a crucial role in determining whether the balance between different elements creates harmony or discord in a composition. It may also serve to characterize the equilibrium or symmetry among various components of an entire piece, ensuring that no single aspect overwhelms the others. Applying proportion should lead to more aesthetically pleasing and functionally efficient outcomes.

However, the rules of proportion have varied across cultures and historical periods, often reflecting the distinct purposes and worldviews of each civilisation. Let’s see.

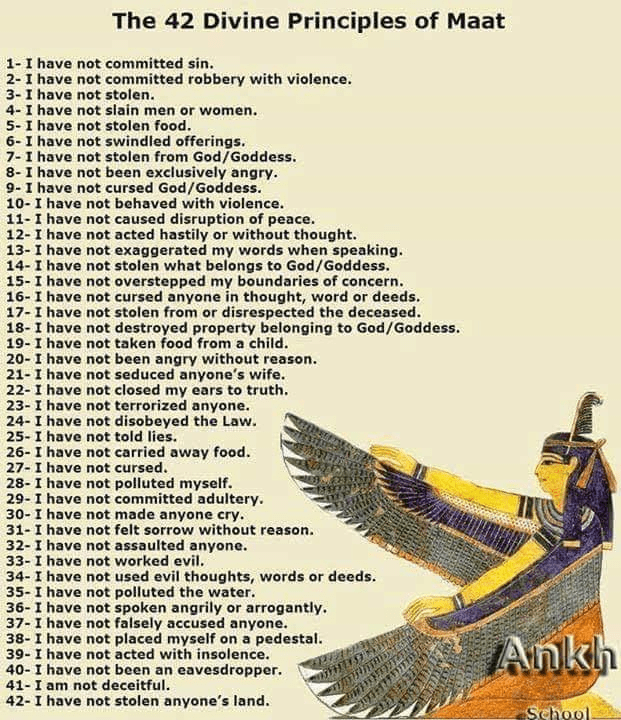

In Ancient Egypt, Ma’at represented the fundamental principles of truth, justice, order, harmony, balance, reciprocity, and propriety. It was a cosmic force that governed the universe, ensuring the proper functioning of the stars, seasons, and the actions of both gods and humans. Ma’at was personified as a goddess, the embodiment of these ideals, and her presence ensured harmony not only in daily life but in the structure of temples, rituals, and art itself.

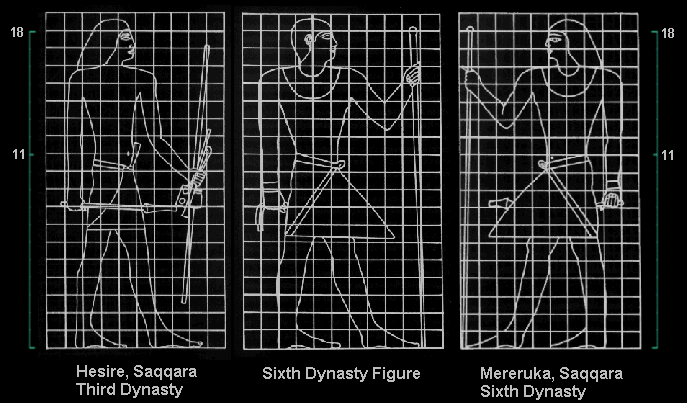

1. Ancient Egypt: Grids, Rituals, and Canon

In Ancient Egypt, proportion was symbolic and reflected beliefs about order and harmony, embodying the principles of ma’at. This idealised use of proportion aimed to convey the significance of figures like gods and pharaohs, allowing artists and architects to communicate messages of power and spirituality, thus transcending the mortal realm and connecting with the divine order.

The widely used 18-square canon divided the human figure into equal parts, ensuring that depictions of the body aligned with divine order rather than human anatomy. This system of grids offered consistency and sacred geometry, particularly in tombs and temple art.

illustrating the use of grids in their artistic and architectural designs. A standing figure should occupy 18 squares from soles to hairline. The knee line should be at 1/3 height, in the 6th square up. The lower buttock line should be at 1/2 height, in the 9th square up. The elbow line should be at 2/3 height, in the 12th square.

Similarly, Egyptian architects employed simple whole-number ratios such as 2:1, 3:2, and √2 in their spatial designs. These proportions were not chosen for visual beauty alone, but to reflect celestial and spiritual alignment, embedding cosmic order into the built environment.

2. Archaic Greece: Echoes of Egypt, Birth of the Canon

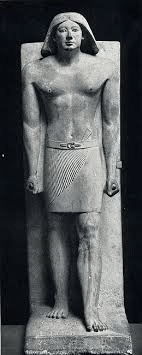

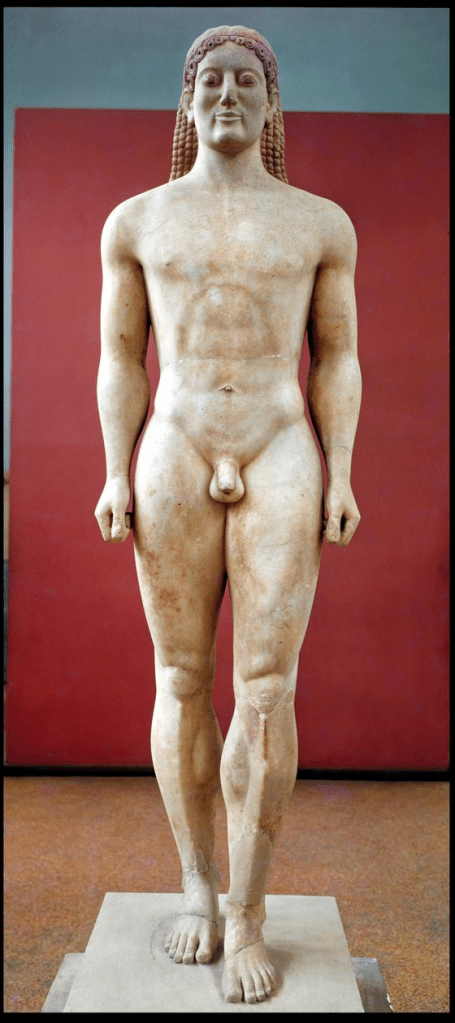

In Archaic Greece, the earliest monumental sculptures, such as the kouroi statues, clearly mimicked the stance and proportionality of Egyptian art. These figures were frontal, rigid, and relied on modular systems that used the head or foot as basic units of measurement. However, by the 5th century BCE, artists like Polykleitos began to challenge these conventions.

Left: The image shows a statue of Ranefer, a High Priest of Ptah and Seker in Memphis during the Old Kingdom of Ancient Egypt. Right: Anavysos Kouros, also known as the Kroisos Kouros, an ancient Greek marble statue from the Archaic period (circa 530 BC).

In his treatise The Canon, Polykleitos introduced a proportional system based on a 1:7 head-to-body ratio, arguing that true beauty arises from measurable harmony. This marked a pivotal shift toward a more dynamic and idealised representation of the human body in Classical sculpture.

3. The Golden Ratio

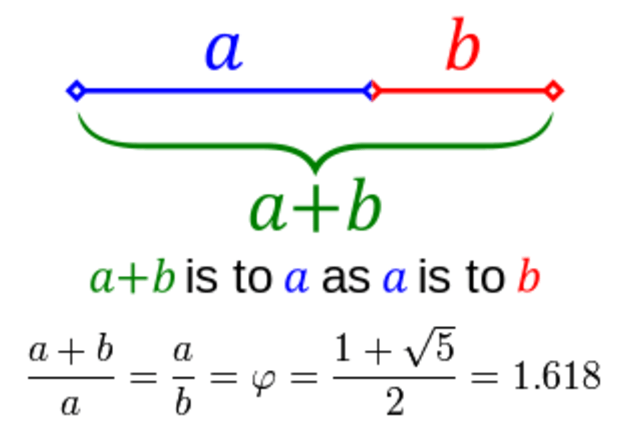

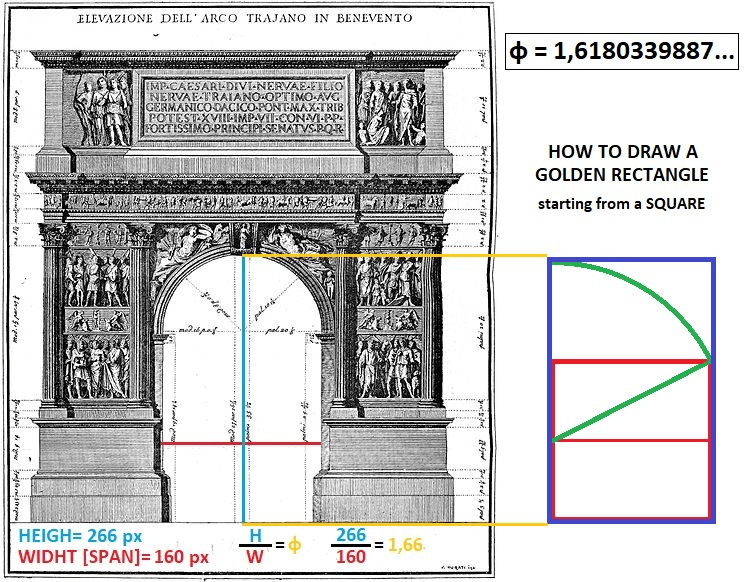

The Golden Ratio is a value that occurs when a line is divided so that the ratio of the whole length to the longer segment equals the ratio of the longer segment to the shorter one. Represented by the Greek letter φ (phi), this ratio is appreciated for its mathematical beauty and its common presence in art, architecture, and nature, defined by the equation: (a + b)/a = a/b = ϕ.

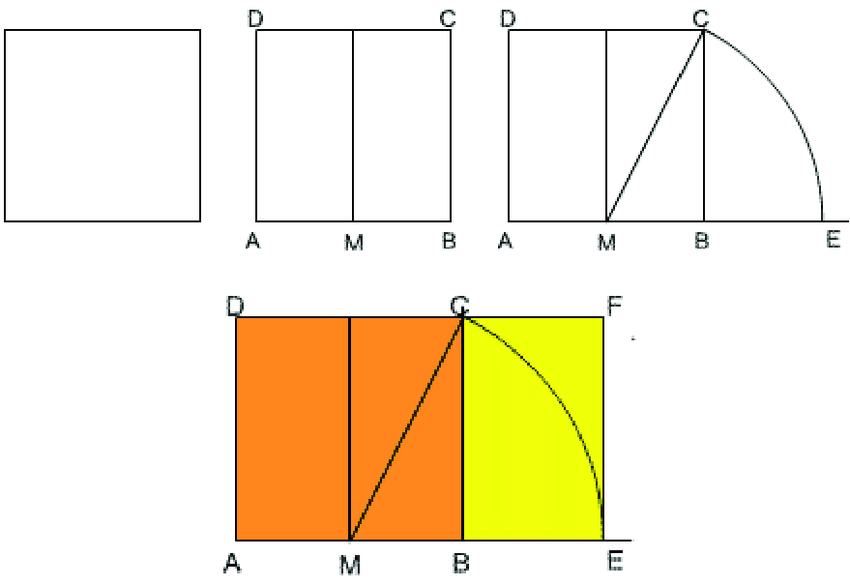

On the left, the mathematical representation. On the right, the geometrical application in the Golden rectangle.

A Golden Rectangle is a rectangle with side lengths in the Golden Ratio (about 1:1.618). When a square is taken from it, the leftover part is also a smaller Golden Rectangle, allowing the pattern to continue infinitely. This repeating beauty makes it useful in architectural planning, art composition, and layout design.

From ancient temples and Renaissance art to modern logos and user interfaces, Golden Rectangles help create designs that feel balanced and pleasing. Their regular proportions are easy for our brains to understand, promoting cognitive fluency and emotional comfort, making them important in neuroarchitecture as well.

4. Renascence: Revival of Proportional Harmony

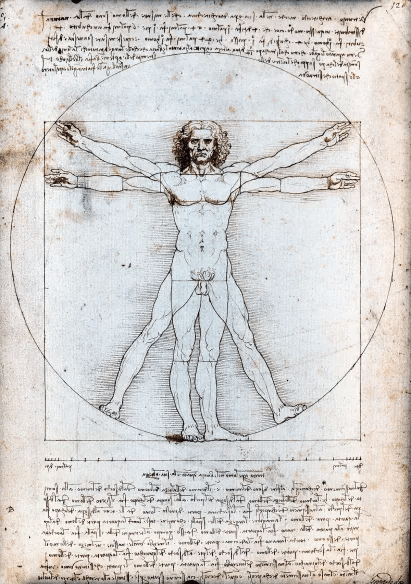

During the Renaissance, proportion experienced a profound revival, and no figure embodied this renewed fascination more than Leonardo da Vinci. Deeply influenced by Classical ideals, Leonardo believed that mathematical harmony mirrored the divine structure of the universe.

His most iconic expression of this belief is the Vitruvian Man—a drawing based on the writings of the Roman architect Vitruvius. In this study, Leonardo illustrated how the human body fits within both a circle and a square, symbolising the union of physical form and cosmic geometry.

Leonardo also used the Golden Ratio, though he referred to it as the Divine Proportion, a term popularised by his collaborator Luca Pacioli, a mathematician and Franciscan friar. Pacioli’s treatise De Divina Proportione (1509), which Leonardo illustrated, celebrated the Golden Ratio as a key to understanding beauty, architecture, and the divine order of nature.

Their work influenced generations of artists and architects, showing that proportion was not just about aesthetics—it was a tool to express universal truths. For Leonardo, geometry was a bridge between art and science, the body and the cosmos, intuition and intellect.

In 1914, three years after visiting the Acropolis in Athens, Le Corbusier wrote “Le Parthénon”—a poetic reflection on architecture’s purpose and artistic meaning. This journal entry, later published posthumously in Voyage d’Orient (1966), reveals how the harmony of Classical Greek architecture deeply shaped his vision. Inspired by painting and literature, his experience at the Parthenon left lasting traces in his design philosophy.

5. Le Corbusier and the Modulor System

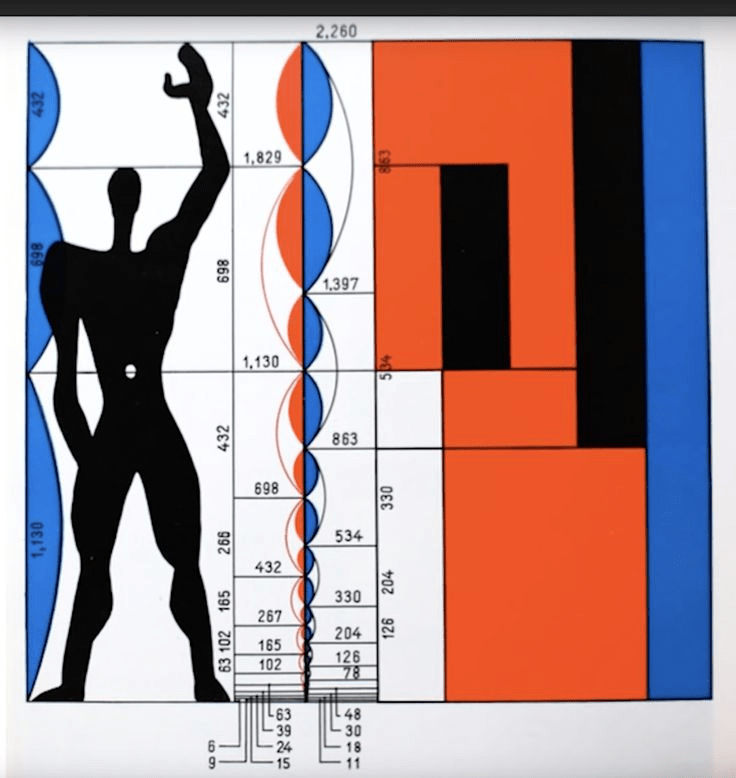

In the 20th century, the conversation around proportion was reignited by Le Corbusier, who sought to connect mathematical order with the needs of the human body. He developed a proportional system called the Modulor, which was based on human measurements, the Golden Ratio, and the Fibonacci sequence. By using a stylised human figure with one arm raised, he generated a scale of proportions intended to bring harmony between architecture and the human form.

Le Corbusier believed the Modulor could serve as a universal measuring tool—a modern canon for architectural design. It was meant to replace arbitrary dimensions with a system rooted in both biological resonance and mathematical precision, making buildings more intuitive, efficient, and aesthetically satisfying.

The Modulor was applied in many of his designs, including the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, and continues to influence discussions on human-centred design today. His work serves as a bridge between ancient ideals of harmony and modern efforts to align design with psychology and cognition.

Golden Ratio: Geometry, Mathematics, and Mysticism

The Golden Ratio has fascinated mathematicians, artists, and architects for centuries.

1. Antiquity

The story of the Golden Ratio begins in Ancient Egypt. It is believed that Pythagoras, one of the earliest Greek philosophers and mathematicians, travelled to Egypt in the 6th century BCE, where he was initiated into the Egyptian Mysteries.

During his time there, he encountered advanced knowledge of geometry, numerical symbolism, and architectural proportion. Though the Egyptians never formalised the Golden Ratio as such, their application is visible in the geometry of temples, pyramids.

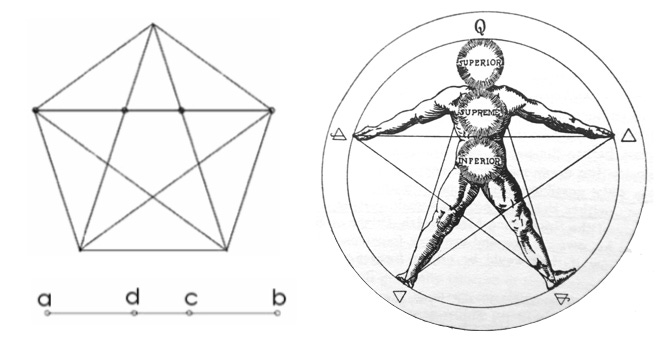

It represents both their school and the numerical principle of the Pentad. Each of the five intersecting lines that form the pentagram contains two Golden Section divisions, making the Golden Ratio visible throughout the star’s geometry. This encoding of ϕ in a single, elegant figure exemplified their belief in a universe governed by harmonic proportions.

Upon returning to Greece, Pythagoras created a school of thought that viewed number and geometry as essential to the universe. His followers, the Pythagoreans, honoured the pentagram as a sacred symbol for its mystical properties and its connection to the Golden Ratio in its shape. They regarded φ (phi) as a mathematical representation of universal harmony—an idea that later impacted Plato and Euclid.

Euclid gave the Golden Ratio its first formal definition in Elements (circa 300 BCE). There he described it as dividing a line so that the ratio of the whole to the larger part is the same as the ratio of the larger part to the smaller.

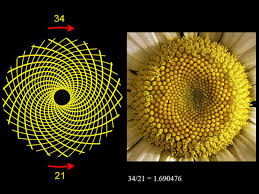

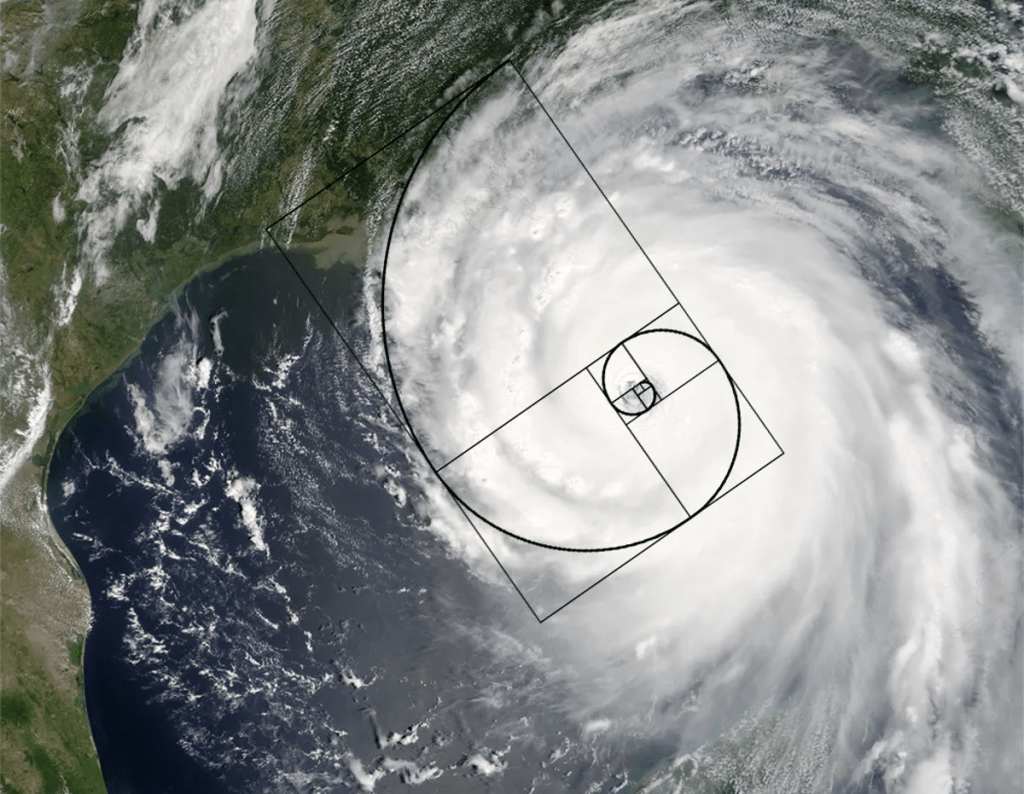

The Fibonacci spiral, derived from the sequence that approximates the Golden Ratio, appears frequently in nature—seen in the unfurling of fern fronds, the arrangement of sunflower seeds, nautilus shells, and even spiral galaxies. This natural recurrence highlights how proportional harmony is not only a human invention, but also a biological pattern embedded in the world around us. These organic shapes resonate with our brains, offering a sense of familiarity, balance, and cognitive ease

2. Middle Ages

But the Golden Ratio’s influence isn’t limited to theory. It recurs in nature itself. The relationship between φ and the Fibonacci sequence emerged in the 13th century. Leonardo of Pisa—also known as Fibonacci—introduced a sequence of numbers (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13…) in his book Liber Abaci. As the sequence progresses, the ratio between successive numbers increasingly approximates φ.

Although developed independently, the Fibonacci sequence reveals the same proportional harmony evident in natural forms, classical design, and visual aesthetics. This convergence of mathematics, nature, and perception underscores why φ continues to be revered as a symbol of balance and beauty.

3. The Renaissance

While rooted in science and observation, many artists of the Renaissance approached geometry and proportion as paths to spiritual insight. Beyond Leonardo da Vinci with his Vitruvian Man and Luca Pacioli, with the “Divine Proportion”, many others looked into philosophy and metaphysic,

Michelangelo, deeply influenced by Neoplatonism and humanist philosophy, used proportion and symbolic gesture to elevate the spiritual resonance of his work. Scholars suggest that the mathematical harmony in his compositions—especially the Sistine Chapel—was a deliberate effort to manifest divine order in visual form.

This mystical approach to design extended to artists like Sandro Botticelli, whose allegorical works fused classical myth with esoteric symbolism, and Albrecht Dürer, who studied sacred geometry and incorporated it into his engravings and treatises on human proportion. For these artists, mathematics was not in conflict with spirituality—it was its language.

Golden Ratio: beyond the myth

The Golden Ratio has long served as a bridge between the rational and the mystical—used not only to shape temples and paintings, but to express a vision of beauty rooted in harmony and proportion. Phi appears like a thread woven through humanity’s enduring effort to understand form, function, and meaning.

Yet as compelling as this narrative is, it is not without its critics. Many researchers urge caution, warning that Phi’s appearance in nature or biology may arise from coincidence, structural necessity, or selective interpretation. In some cases, the desire to find ϕ leads to confirmation bias—projecting patterns where none were consciously intended.

These sceptical voices offer a necessary counterbalance: while the Golden Ratio is undeniably elegant, its presence should be approached with critical rigour, not romanticised without evidence.

Still, in architecture—and especially within the growing field of neuroaesthetics—Phi remains a powerful lens through which we explore how proportion shapes not only space, but perception itself.

The Neuroscience of Proportion

Even though beauty is frequently regarded as subjective, neuroscience indicates that specific aspects of it can be identified and quantified in the brain. Functional MRI (fMRI) studies have shown that when people perceive something as beautiful—be it a building, sculpture, or painting—specific regions of the brain become more active, especially the medial orbitofrontal cortex, an area linked to pleasure, reward, and decision-making.

Visual characteristics such as harmonious proportions, balance, and natural rhythms tend to stimulate this part of the brain more consistently. This supports the idea that, although beauty is not a fixed or universal truth, it typically follows visual principles that our brains are wired to recognise, enjoy, and remember.

What the Brain Sees—and Feels

Research in neuroscience is helping us understand why certain proportions, including the Golden Ratio, feel so pleasing. A 2009 study by Cela-Conde and colleagues showed that when people view shapes based on the Golden Ratio, it activates the medial orbitofrontal cortex—a part of the brain linked to reward and pleasure.

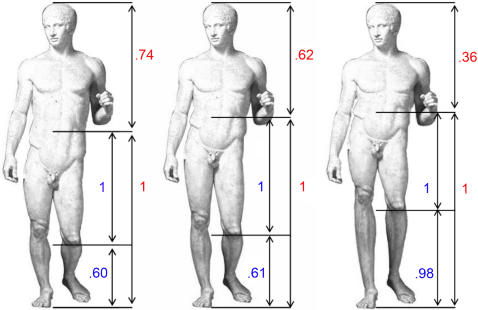

This image was used in the study: The Golden Beauty: Brain Response to Classical and Renaissance Sculptures. Authors: Cinzia Di Dio , Emiliano Macaluso, Giacomo Rizzolatti

The original sculpture by Polykleitos appears at the centre and reflects canonical Classical proportion, closely approximating the Golden Ratio (1:1.618). To its left, a modified version shortens the legs in relation to the trunk (ratio = 1:0.74), and to its right, another version exaggerates leg length (ratio = 1:0.36). All three were used in behavioural testing; only the central and left images were used in fMRI analysis. The centre image was rated as most beautiful (100%), while the left was judged ‘ugly’ by 64% of participants. The fMRI scans revealed distinct neural activations depending on perceived aesthetic value.

Another study by Di Dio et al. (2007) found that classical sculptures with ideal proportions triggered activity in the insula and amygdala, regions associated with emotional processing and internal resonance. These findings suggest that our appreciation of proportion isn’t just cultural or aesthetic—it’s also biological. Our brains seem to recognise and respond positively to cognitive ease, emotional balance, and intrinsic order in what we see.

Conclusion: A Harmony Worth Reclaiming

Throughout history, proportion has served as a bridge between the tangible and the transcendent—used not only to structure buildings and bodies but to craft experiences that resonate with the mind and spirit. From the sacred geometry of Egypt to the idealised forms of Classical Greece, from Leonardo’s Divine Proportion to Le Corbusier’s Modulor, designers have sought to align their creations with something greater: a harmony we feel even if we cannot always explain.

Today, as neuroscience reveals how our brains respond to proportional order—lighting up with pleasure, clarity, and emotional ease—it becomes clear that these ancient tools still hold relevance. In an era of sensory overload and environmental stress, reintroducing principles like the Golden Ratio into our architectural vocabulary is not a nostalgic gesture, but a necessary act of design empathy.

By revisiting the proportional wisdom of the past through the lens of neuroarchitecture, we can craft spaces that don’t just look good but feel right—spaces that calm, orient, and uplift the human experience.

The Parthenon is not just a building—it is a dialogue across time. A book etched in marble, still speaking to those who listen.

Personal Reflection

For me, the undisputed beauty of the Parthenon lies not only in the precision of its columns or the masterful execution of its frieze, but in something more profound: the way its apparent simplicity reveals a deeper truth—the harmony of its proportions and the human yearning for meaning and cosmic order.

It stands like an open book written in geometric language—a silent dialogue across time. A space where mathematics becomes metaphor, and architecture reaches for the transcendent. Its lines and ratios speak not only of Egyptian influences, but also of a distinctly Greek idiosyncrasy—shaped in harmony with the spirit of its age.

The Parthenon is more than an ancient temple; it is a lesson in stone, a silent book of geometry and meaning. For those who stand before it—or study its lines—it becomes a place of pilgrimage. A space where connection, knowledge, inspiration, and intellectual wonder converge. Not merely to be seen, but to be understood. To be felt.

What spaces in your own life reflect proportion, intention, or calm? The Golden Ratio may not be a universal rule—but it remains a powerful reminder of our search for harmony

References

Cela-Conde, C. J., Ayala, F. J., Munar, E., Maestú, F., Nadal, M., Capó, M. A., … & Marty, G. (2009). Sex-related similarities and differences in the neural correlates of beauty. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(10), 3847–3852.

Di Dio C, Macaluso E, Rizzolatti G. The golden beauty: brain response to classical and renaissance sculptures. PLoS One. 2007 Nov 21;2(11):e1201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001201

Euclid. (circa 300 BCE). The Elements (Book VI, Proposition 30). In T. L. Heath (Ed. & Trans.), The Thirteen Books of Euclid’s Elements (Vol. 2). Dover Publications, 1956.

Pythagoras and the Philosophy of Number (5 of 5). https://thewisdomtradition.substack.com/p/pythagoras-and-the-philosophy-of-c33

Le Corbusier between sketches. A graphic analysis of the Acropolis sketches https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/22ae/c1ae6c42911fec839a4aeebd4bdae930a42a.pdf

More than a neuroanatomical representation in The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo Buonarroti, a representation of the Golden Ratio https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26182895/

The Relation of Golden Ratio, Mathematics and Aesthetics https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325403361_The_Relation_of_Golden_Ratio_Mathematics_and_Aesthetics/link/5b0c2e224585157f871ca6b8/download?_tp=eyJjb250ZXh0Ijp7ImZpcnN0UGFnZSI6Il9kaXJlY3QiLCJwYWdlIjoicHVibGljYXRpb24iLCJwcmV2aW91c1BhZ2UiOiJfZGlyZWN0In19

The Design of The Great Pyramid of Khufu https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00004-014-0193-9

Phi in physiology, psychology and biomechanics: The golden ratio between myth and science https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0303264717304215