Could you share a morning shower with your partner—not for romance, but because your city’s mayor told you it would help save water? In Bogotá, 2024, this suggestion became reality. A severe drought, intensified by the El Niño phenomenon, pushed the Chingaza reservoir system to historic lows.

Simultaneously, maintenance at the Tibitoc water treatment plant added pressure to an already strained supply. Authorities divided the city into sectors, rotating daily water cuts across households. The restrictions remained until April 2025 when rainfall replenished critical reserves.

For months, Bogotá lived in tension. Buckets lined bathrooms. Fountains fell silent. Every drop mattered. It was raining in Bogotá—but not in Chingaza. But the lesson went beyond inconvenience:

Despite being one of Bogotá’s main sources of water, the Chuza Reservoir in Chingaza National Park showed alarming drops in 2024. El Niño disrupted rainfall patterns across the region, and with record-low precipitation, the fragile balance between ecosystem conservation and water supply came into focus. One rainy month wasn’t enough to offset the crisis.

If water can run out in one of the rainiest capitals on Earth, it can run out anywhere.

Climate change is no longer a distant threat. It is altering how we live—drying our rivers, flooding our cities, and exposing our failures in urban design. We continue to build as if water is predictable, infinite, and irrelevant.

This article is both a wake-up call and a vision:

What if our homes, schools, and cities were designed not to drain water away, but to cherish it?

From Drought to Deluge: A Planet Out of Balance

While Bogotá rationed its dwindling supply, Central Texas faced the opposite disaster.

Tragedy in Texas Hill Country

On 4 July 2025, relentless storms dropped 10 to 20 inches (ca. 51 cm) of rain over parts of Texas in a matter of hours. The Guadalupe River rose by more than 20 feet (ca. 6 m) in 90 minutes, sweeping away campsites, homes, and bridges. More than 120 people died—including dozens of children—making it the deadliest inland flood in the U.S. in decades (The Independent, 2025).

This wasn’t unforeseeable. Central Texas, nicknamed “Flash Flood Alley,” is notorious for rapid flooding. But despite decades of warnings, communities lacked the infrastructure and alert systems to respond in time. Lives were lost not just to water—but to inaction.

A Global Pattern of Extremes

These events aren’t isolated. They’re symptoms of a global water imbalance:

- Rain disappears where it’s expected.

- Floods strike where water is scarce.

- Droughts and deluges occur side by side.

From India’s collapsing riverbanks to Brazil’s overflowing streets, the climate crisis is destabilising our most vital resource.

Water is no longer predictable. It arrives in torrents or vanishes without warning—and our cities are built for neither.

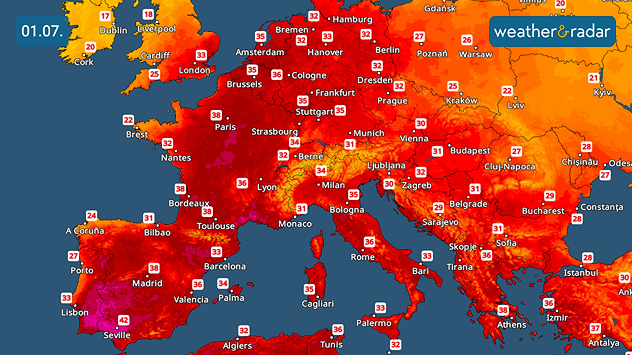

Temperatures soared across the continent, with many cities recording highs of 38–40°C. From Lisbon to Istanbul, this extreme heat disrupted daily life, strained infrastructure, and underscored the urgency of climate adaptation in urban design.

Heatwaves and Cold Snaps

Across Europe, another pattern emerges: unrelenting heat. In the summer of 2025, temperatures soared near 40°C across cities from Istanbul to Madrid. Street performers collapsed in costumes, airports like Marseille’s were shut down due to nearby wildfires, and residents struggled with the unbearable weight of heatwaves. Yet despite the suffering, many governments are scaling back climate policies meant to prevent worse.

Meanwhile, in stark contrast, Patagonia in southern Argentina recorded record-breaking cold waves. In July 2025, temperatures in towns such as Perito Moreno and Río Gallegos plunged well below -10°C, accompanied by heavy snowfall and frost (Deutsche Welle, 2025). This sharp climatic divergence, happening simultaneously across hemispheres, highlights the instability of global weather patterns.

Cities must adapt now—before these extremes become the new normal.

The urban skyline of Bogotá reflects its rapid growth—yet beneath its concrete and glass lies a complex relationship with water. Despite being one of the rainiest capitals in the world, the city faced a severe drought in 2024, revealing how fragile urban water systems can be in the face of climate change.

Ancient Lessons: What the Muisca Knew That We Forgot

Long before concrete and drainpipes, the Bogotá savanna was nourished by an advanced Indigenous water management system built by the Muisca people. Through a network of canals, aqueducts, and wetlands, they worked with the land—not against it—to regulate water cycles across the high plateau.

These systems vanished under colonial rule, replaced by extractive approaches designed to drain and dominate the landscape. But recent aerial photography and archaeological research have begun to uncover remnants of this once-thriving hydraulic infrastructure. Scholars now believe that reconnecting with these ancestral practices could offer modern Bogotá—and other cities worldwide—sustainable blueprints for water resilience

The past isn’t gone. It’s buried beneath us, waiting to teach us how to live again.

Rethinking Water in Design: Cities That Work with the Rain

To restore balance, we must design systems that work with water—not against it. Around the world, cities are beginning to rethink the role of water in urban life.

A. Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS)

SuDS mimic natural water cycles to manage rainfall. Examples include:

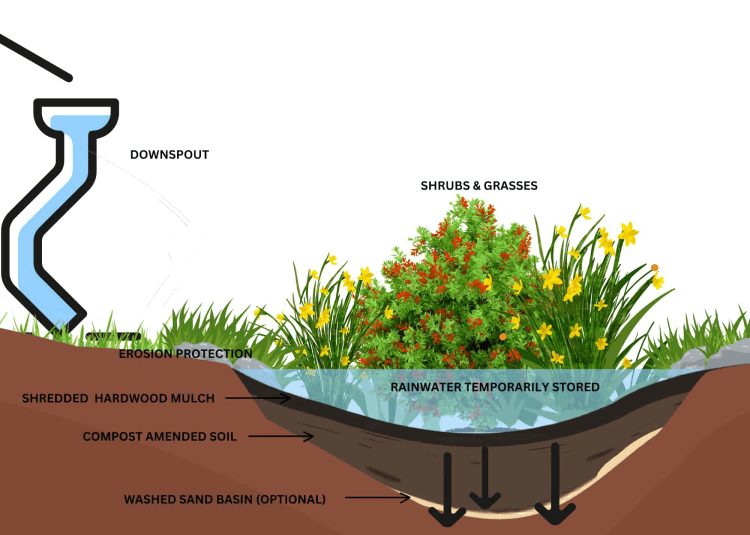

- Rain gardens: Planted basins that absorb and filter run-off

- Bioswales: Vegetated channels guiding water through green corridors

- Permeable pavements: Materials that allow water to infiltrate the soil

- Underground tanks: Hidden storage beneath parks or plazas

In London, rainwater is collected beneath micro-parks and used to irrigate surrounding vegetation. In Mansfield, the sponge city model introduced over 340 SuDS elements, capable of storing 58 million litres of water for more than 90,000 people.

B. The Power of Rain Gardens

Rain gardens are small-scale, low-tech interventions with large impact:

- Absorb up to 30% more water than a typical lawn

- Filter pollutants

- Recharge groundwater

- Support biodiversity

- Cool urban heat

They turn rain into a living system—visible, beautiful, and restorative.

C. Buildings That Harvest and Celebrate Rain

Architectural strategies for water-conscious design include:

- Rooftop rainwater collection

- First-flush diverters to discard initial dirty run-off

- Multi-stage filtration (sediment, carbon, UV)

- Transparent tanks and visible pipe systems

- Indoor water features for sensory engagement and education

In schools and hospitals, these features can be both calming and instructional—helping children and patients connect emotionally to water’s journey.

D. Lessons from Low-Tech Traditions

In arid zones like the Gobi Desert or the Sahel, communities have long used traditional methods to trap and store rain:

- Tree planting to stabilise soil and draw moisture

- Stone bunds and zai pits to collect run-off

- Roofless cisterns and terracing to slow erosion

These ancestral systems prove that smart design doesn’t need to be high-tech—it needs to be rooted in respect for place.

We are not running out of water—we are mismanaging it.

Each pit, typically 20–30 cm wide and deep, is dug into degraded, compacted soil to capture scarce rainfall. Farmers fill them with organic matter, which attracts termites and improves infiltration. When rain does fall, it is absorbed instead of lost to runoff, rehydrating the land and boosting crop yields. Used across drylands in the Sahel, this technique is a model of low-cost, climate-resilient design that restores both water cycles and food security.

Zai Pits in the Sahel: Ancestral Ingenuity for Water Retention

Each pit, typically 20–30 cm wide and deep, is dug into degraded, compacted soil to capture scarce rainfall. Farmers fill them with organic matter, which attracts termites and improves infiltration. When rain does fall, it is absorbed instead of lost to run-off, rehydrating the land and boosting crop yields. Used across dry lands in the Sahel, this technique is a model of low-cost, climate-resilient design that restores both water cycles and food security.

A Misplaced Obsession

As we spend billions searching for traces of ancient water on Mars, we neglect the systems needed to manage the living water that surrounds us here on Earth.

What does it say about us that we seek droplets in distant planets, while letting our rivers and reservoirs run dry?

Exploration has value. But so does responsibility. Before we colonise the stars, we must learn to live more wisely on the only planet we know that has water—and life.

Can Rainwater Be Drinkable?

Yes—but only through thoughtful treatment and design.

Rainwater may be clean when it falls, but once it hits rooftops, it can pick up bacteria, pollutants, and heavy metals. Without filtration, it’s unsafe to drink. Yet, with the right systems, it becomes an abundant and renewable supply.

Safe Rainwater Use Requires:

- First-flush diverters to discard the dirtiest run-off

- Sediment and carbon filters to remove particles and chemicals

- UV or nanofiltration to kill pathogens

- Sealed, shaded tanks for storage

A 2023 review in Frontiers in Environmental Science highlights the importance of designing systems across three stages: collection, transmission, and treatment. In the UK, experts caution against using untreated rainwater for drinking, but confirm that filtered systems are safe and effective.

When buildings harvest and purify rain on-site, they become resilient, sustainable, and self-teaching. Water becomes not just a resource—but a relationship.

What We Build, We Remember

Floods and droughts are not opposites—they are reminders. Both warn us of the same thing: we’ve forgotten how to live with water.

But what if we remembered? What if we designed not to dominate water, but to learn from it?

- What if every school harvested its rain?

- What if every plaza cooled its air with filtered fountains?

- What if buildings made the water cycle visible, legible, and shared?

We are running out of time—but not of ideas.

Let us design with water in mind—before it disappears, or overwhelms us all.

Key Message

Without water, there is no life. Scarcity and excess both generate instability and anxiety. We must shift our mindset—and our design practices—toward protection, visibility, and stewardship.

🌍 What could you do, in your home or city, to treat rain not as waste—but as a gift?

References

Bloomberg. (2024). Bogotá water restrictions reshape life from homes to businesses. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2024-06-20/bogota-water-restrictions-reshape-life-from-homes-to-businesses

Fountain Filters. (n.d.). Can you drink rainwater?. Retrieved from https://www.fountain-filters.co.uk/blog/can-you-drink-rainwater-harvesting-uk-51.html

Modern Farmer. (2021). How to build a rain garden. Retrieved from https://modernfarmer.com/2021/05/how-to-build-a-rain-garden

The Flood Hub. (n.d.). How your garden can help manage flood risk. Retrieved from https://thefloodhub.co.uk/blog/how-your-garden-can-help-manage-flood-risk

The Independent. (2025). Texas floods live: At least 120 dead and dozens missing after flash floods hit Hill Country. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/texas-floods-live-camp-mystic-map-weather-alerts-b2786120.html

Wang, W., Wu, J., Zhang, X., Li, H., & Wang, Z. (2023). Urban rainwater utilization: A review of management modes and harvesting systems. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 11, Article 1025665. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1025665

What is a rain garden? Benefits to Your Landscape Design. https://warelandscaping.com/resources/rain-garden/

Are we heading for ‘managed retreat’? Everything you need to know about floods. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/jul/08/explainer-flood-risk-rising-around-the-world-what-can-we-do-to-adapt?utm_term=687207f74b9af38a46fd17081fb0775d&utm_campaign=SaturdayEdition&utm_source=esp&utm_medium=Email&CMP=saturdayedition_email

Explained: Extreme cold in Argentina’s Patagonia region. https://www.dw.com/en/explained-extreme-cold-in-argentinas-patagonia-region/a-69730974

Danjuma, M. N., & Mohammed, S. (2015). Zai Pits System: A Catalyst for Restoration in the Drylands. IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT), 8(2), 2319–2372. https://doi.org/10.9790/2380-08210104

Fotografías aéreas revelan un complejo sistema hidráulico Indígena en Bogotá. https://eos.org/articles/aerial-photographs-uncover-bogotas-indigenous-hydraulic-system-spanish#:~:text=La%20desaparici%C3%B3n%20del%20sistema%20hidr%C3%A1ulico,hacerse%20ricos%20r%C3%A1pidamente%20con%20oro%E2%80%9D.