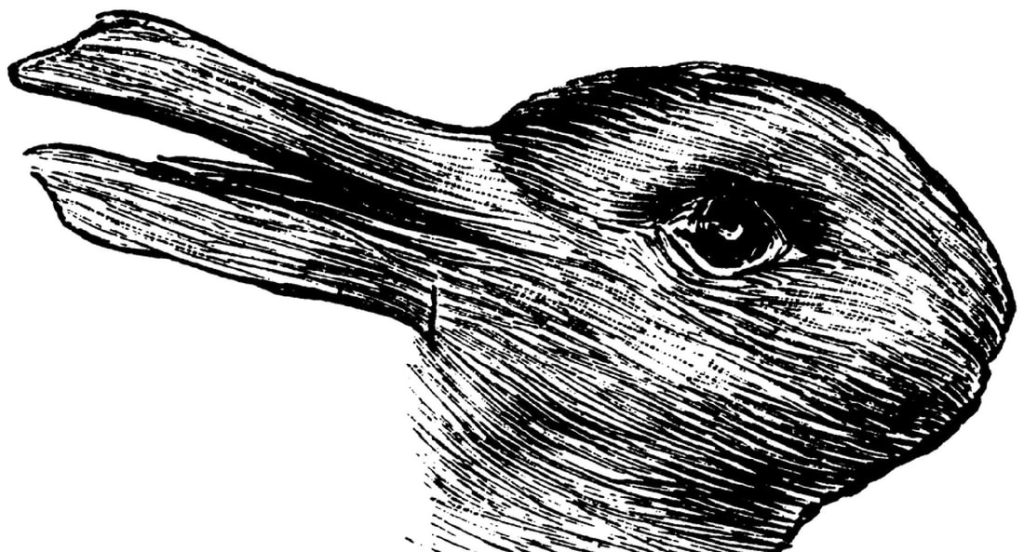

Where you see a duck, others might see a rabbit. Who’s right — and who’s wrong?

In truth, both are correct. This famous duck–rabbit illusion, first printed in Fliegende Blätter in 1892 and later popularised by psychologist Joseph Jastrow, demonstrates how the same arrangement of lines can produce two entirely different realities. Our brains can switch between them instantly — a phenomenon known as multistable perception.

The drawing never changes — only our interpretation does. This shifting viewpoint captures the essence of Gestalt theory, which emerged in the early twentieth century with the work of Max Wertheimer, Wolfgang Köhler, and Kurt Koffka.

The German word Gestalt translates roughly as “form” or “configuration”. Gestalt psychologists argued that we perceive wholes before parts, and that meaning arises not solely from the sensory information we receive, but from how our minds organise and frame it.

Though Gestalt theory predates modern neuroscience, research into vision and brain processing has confirmed many of its principles — revealing that the human brain is wired to seek order, pattern, and meaning in the world around us.

Gestalt principles aren’t just abstract theories — they are rooted in our biology, shaping how we interpret every visual environment we encounter.

It is used for numerous psychological and emotional conditions, where it is important to foster awareness, personal growth, and self-esteem. By focusing on the here and now, the patient can direct their attention to the present and become aware of how they have arrived at their current situation.

Gestalt and the Brain

Modern neuroscience confirms that our brains naturally group and organise visual information, reducing cognitive load and speeding recognition. This tendency explains why well-organised visuals — whether in a book, a building, or a website — feel easier to navigate.

Research in neurophysiology, brain imaging, and computational modelling shows that Gestalt principles — such as proximity, similarity, and continuity — are reflected in the brain’s neural architecture. Visual perception arises from the coordinated activity of neurons across multiple brain areas, which integrate edges, colours, and motion into coherent wholes.

These neural grouping mechanisms allow us to recognise objects and patterns rapidly, making Gestalt not just a psychological theory but a reflection of how our brains are wired to process the world.

Gestalt thinking also influenced psychotherapy. Gestalt therapy, developed by Fritz Perls and others in the mid-twentieth century, focuses on self-awareness in the “here and now”, encouraging individuals to recognise how they perceive and respond to their current circumstances.gate.

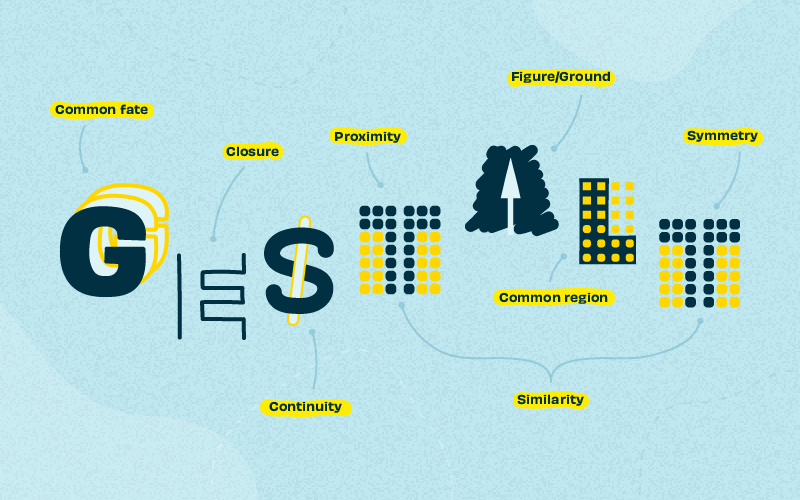

Core Principles of Gestalt Perception

1. Proximity

Elements placed close together are perceived as belonging to the same group.

Example: Chairs arranged in clusters in a public square feel like distinct social zones.

2. Similarity

Objects sharing shape, size, colour, or texture are considered related.

Example: Matching signage colours in a hospital help patients navigate intuitively.

3. Continuity (Good Continuation)

We see lines and curves as continuous, even when interrupted.

Example: A row of trees leading to a building draws the eye along a clear visual path.

4. Closure

The brain fills in gaps to perceive complete forms.

Example: A dotted outline of a square still registers as a solid shape.

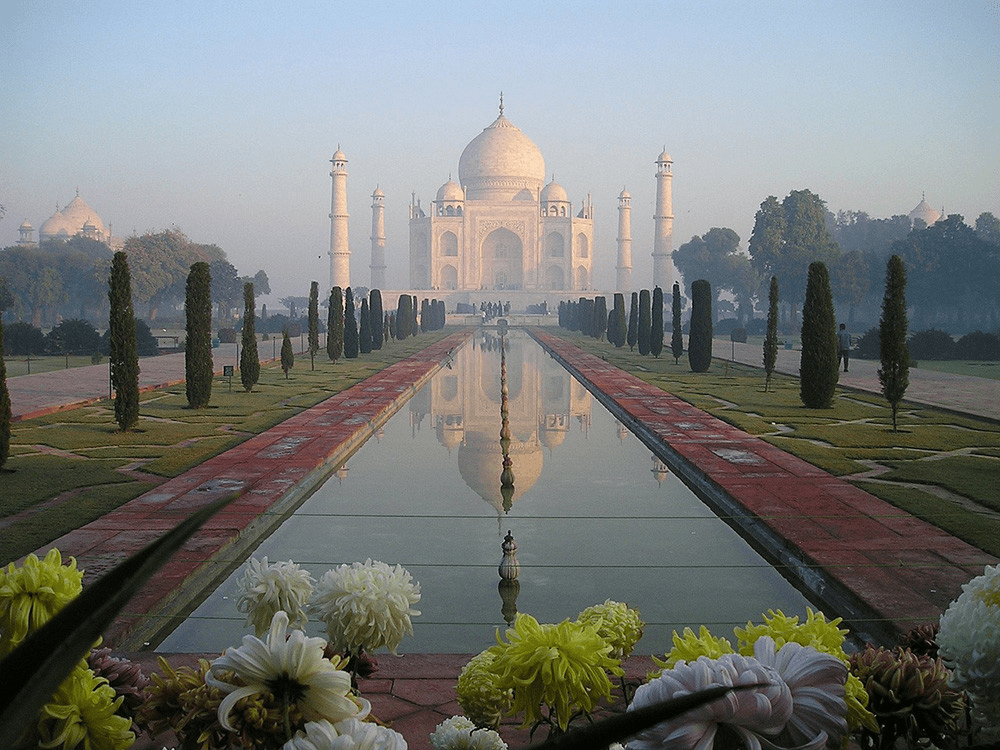

5. Symmetry and Order

Symmetrical figures feel stable and complete.

Example: The façade of the Taj Mahal exudes harmony through its perfect symmetry.

6. Figure–Ground

We distinguish a main subject (figure) from its background.

Example: A balustrade can be read as solid pillars or as the spaces between them.

7. Common Fate (Common Direction)

Elements moving in the same direction appear unified.

Example: Repeated arches in a corridor guide movement and create rhythm.

Gestalt Theory applications

Gestalt principles help arrange information for clarity and impact. Figure–ground creates engaging illusions (left), and similarity builds visual cohesion (right).

1. Graphic design

Gestalt principles are a cornerstone of graphic design, shaping how information is organised for clarity, hierarchy, and visual impact. Proximity groups related text and images into meaningful clusters; figure–ground relationships create depth and visual intrigue; and similarity in colour, shape, or typography unifies a layout. These rules are not just aesthetic preferences — they help reduce cognitive load, allowing viewers to absorb information quickly and efficiently.

Gestalt thinking is critical — studies show users form an opinion of a webpage in just 50 milliseconds. If nothing captures attention instantly, visitors will leave.

2. UX/UI design

In the digital realm, Gestalt thinking is critical. Research shows that users form an opinion of a webpage in as little as 50 milliseconds. If order and relevance aren’t conveyed immediately, visitors may leave without engaging. Applying proximity, continuity, and similarity to interface design guides attention, improves navigation, and creates seamless experiences. The same principles that make a poster visually striking can make an app feel intuitive and effortless to use.

These same principles shape how we experience spaces. Symmetry reassures and balances (left), figure–ground plays with our interpretation. Your perception flips between object and background (right).

Left: Repetition and symmetry in a minimalist motif, illustrating Gestalt principles of similarity and continuity.

Right: A vibrant geometric tapestry where colour, rhythm, and pattern interact, demonstrating how complexity can still feel cohesive through Gestalt grouping.

3. Architecture and interior design

Gestalt principles are embedded in how we navigate and experience spaces. Proximity shapes social interaction: clustered seating encourages conversation, while dispersed arrangements invite solitude. Similarity in materials or colours unifies complex buildings, while continuity in elements like colonnades or tree-lined paths guides movement. Figure–ground adds visual interest, as in screens or patterned façades that can be read as solid or void.

There are, in truth, multiple realities — one based on physical materiality, and another shaped by perception.

The Subjectivity of Perception

While our perceptual mechanisms share common patterns, our interpretations are deeply individual. Culture, memory, emotion, and neurodiversity all influence how we read an image or experience a space. In truth, there is no single “correct” perception — only multiple realities, one based on physical form and another shaped by the mind.

Gestalt reminds us that design is never neutral. By understanding how people instinctively group, separate, and interpret visual information, we can create spaces — physical or digital — that are both clear and rich in possible meanings. In doing so, we design not only for order and usability, but also for diversity in interpretation and experience.

Final Thoughts

Gestalt theory began as a set of perceptual insights, yet neuroscience now confirms its biological foundations. Our brains don’t simply record the world — they actively organise it, binding edges, colours, textures, and movements into coherent patterns.

Neural grouping mechanisms reflect the Gestalt laws of proximity, similarity, and continuity, enabling us to recognise and interpret complex scenes instantly. For architects, designers, and planners, these principles are far more than stylistic preferences — they engage deep, hardwired processes that influence how people see, feel, and behave in a space.

By aligning design decisions with the brain’s innate search for order and pattern, we can create environments that are not only visually harmonious but also cognitively clear and emotionally supportive.

Research on architectural probabilism (Al-Alwan et al., 2024) reinforces this: distinctive landmarks and clear linear elements strongly shape mental maps and wayfinding. Applying Gestalt’s focus on form, rhythm, and contrast allows designers to craft spaces that are both beautiful and intuitively legible.

References

Al-Alwan, H. A. S., Al-Bazzaz, I. A., & Ali, Y. H. M. (2024). The potency of architectural probabilism in shaping cognitive environments: A psychophysical approach. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 13(4), 780–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2021.06.008

Lindgaard, G., Fernandes, G., Dudek, C., & Brown, J. (2006). Attention web designers: You have 50 milliseconds to make a good first impression! Behaviour & Information Technology, 25(2), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/01449290500330448

Droste, M. (2006). Bauhaus 1919–1933. Thames & Hudson.

Wagemans, J., Elder, J. H., Kubovy, M., Palmer, S. E., Peterson, M. A., Singh, M., & von der Heydt, R. (2012). A century of Gestalt psychology in visual perception: I. Perceptual grouping and figure–ground organisation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(7), 383–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.01.006

Gestalt theory and Bauhaus – A Correspondence https://www.academia.edu/4775522/Gestalt_theory_and_Bauhaus_A_Correspondence_Between_Roy_Behrens_Brenda_Danilowitz_William_S_Huff_Lothar_Spillmann_Gerhard_Stemberger_and_Michael_Wertheimer_in_the_summer_of_2011

Video: Bauhaus, Gestalt Theory, and Problem-Solving: Thinking Outside the Box

More Than Parallel Lines: Thoughts on Gestalt, Albers, and the Bauhaus https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/433/oa_edited_volume/chapter/3072090

One thought on “The Science of Perception: How Gestalt Principles Influence Us”