Shadows on the Wall

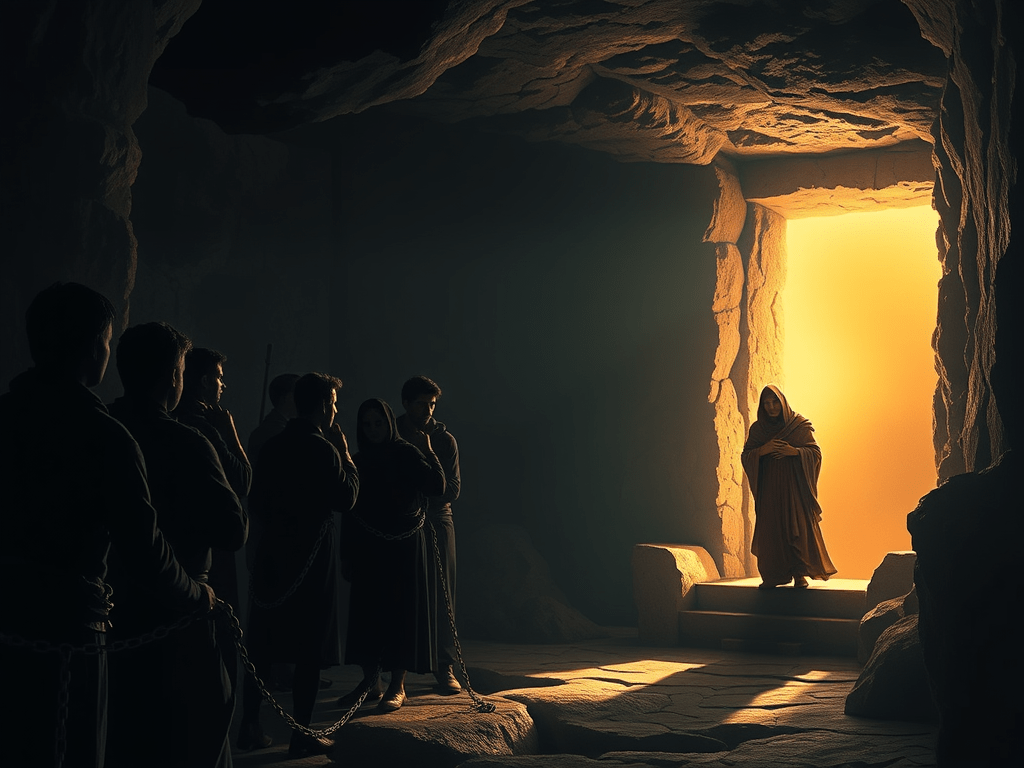

Well over two thousand years ago, Plato imagined a group of prisoners chained inside a cave. For them, reality was nothing more than shadows cast on the wall—flickering shapes mistaken for the whole truth. Only when one prisoner was freed and stepped into the sunlight did he realise that what they had seen was not reality itself, but a distorted projection of it.

Plato’s allegory of the cave reminds us that perception is never direct. We do not see the world “as it is,” but only through filters, interpretations, and limitations. What we call reality is already a version—partial, constructed, useful, but incomplete.

Today, neuroscience and physics echo this ancient insight: perception is subjective, observer-dependent, and always tied to the mind that experiences it. Which leads us to a question as urgent now as it was in Plato’s time: if we all inhabit different versions of reality, what does it mean to say something is real?

What Is Perception?

Perception is not a camera recording reality; it is the brain’s ongoing construction of a model of the world. Our senses provide fragments—light, sound, chemical signals—but it is the brain that interprets, fills gaps, and creates coherence.

Gestalt psychology showed us that the brain instinctively seeks patterns: we group shapes, separate figures from backgrounds, and “fill in” missing parts. This helps us navigate complexity, but also means that what we perceive is never neutral — it is always an interpretation. (See our article on Gestalt for a deeper dive into these principles.)

Culture, memory, and emotion all influence this process, so no two people construct the same reality. For some, a space feels calm and welcoming; for others, overstimulating. The environment may be identical, but the lived experience is not.

Everyday examples remind us of this: optical illusions reveal the brain’s shortcuts; at a party, you can pick out your name from the noise (the “cocktail party effect”); stressed, minutes feel endless, while in joy, hours seem to vanish. The same conditions — light, sound, time — are experienced differently depending on the observer.

Have you ever walked into a space that made you uneasy, even though nothing obvious was “wrong”?

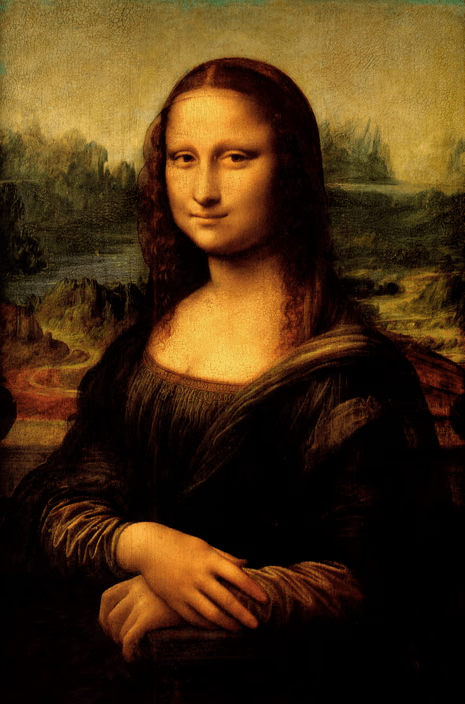

Yet in the Louvre today, many see only a small portrait behind glass, surrounded by crowds. Same painting, two realities — one shaped by art, the other by experience.

The Case of the Mona Lisa

Few works of art illustrate this better than Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. For centuries, the painting has been celebrated as the pinnacle of artistic genius. Yet, when many visitors finally see it in the Louvre, their reaction is anticlimactic: a small portrait, behind glass, crowded by tourists and smartphones.

Why the contrast? A critic, trained for years in Leonardo’s technique, may see subtle mastery, layers of symbolism, and psychological depth. A tourist, pushed forward in the crowd, may see only hype. Both experiences are valid — and both are shaped by context and expectation.

The painting has not changed in 500 years. What changes is the gaze of the observer. Reality is not simply what sits on the wall; it is what happens between the object and the mind that beholds it.

If two people see the same painting but leave with opposite reactions, which one has seen reality?

Neuroscience: Reality as a “Controlled Hallucination”

Modern neuroscience confirms this. As Anil Seth explains in Scientific American, perception is essentially a “controlled hallucination”: the brain’s best guess about a world hidden behind a sensory veil.

- Sensory overload: Our senses deliver around 11 million bits of data every second. Our conscious mind can handle about 50. The rest is filtered out.

- Bottom-up vs. top-down: Sensory input (light, sound) is combined with prior knowledge and expectation. This is why we can read a word even if letters are missing, or hear meaning in a garbled conversation.

- Bias and belief: If you expect the world to be hostile, your brain notices hostility more easily — reinforcing the belief.

In short, we never see reality in its raw form. We see a brain-generated version, shaped by survival needs, culture, and emotion.

As Donald Hoffman argues, perception did not evolve to show us the truth of reality — it evolved to hide most of it, giving us only the version we need to survive.

Donald Hoffman’s — Interface Theory of Perception

Our eyes reveal only the external image, yet beneath the surface lie hidden structures that also define who we are.

Worlds Within Worlds

Our perception of the world is sharply limited by biology. Human eyes, for example, are tuned to a narrow slice of the electromagnetic spectrum — just 400 to 700 nanometres — what we call visible light. Yet surrounding us at every moment are countless other wavelengths: infrared, ultraviolet, X-rays, gamma rays, and radio waves.

Take X-rays. They pass through us constantly, unseen. With the help of machines, however, they reveal what our eyes cannot: the skeletal structure beneath our skin. The bones were always there, but invisible to unaided perception.

Or consider bats. They navigate their environment not primarily through vision but through echolocation. They perceive a world of acoustic landscapes that humans are unable to detect by emitting high-frequency calls and interpreting the echoes. Similarly, bees can perceive ultraviolet patterns on flowers — colours invisible to us but vital to their survival.

Virtual reality offers a striking modern example. Put on a headset, and the brain responds to illusions as if they were real: a frightening scene can trigger palpitations, sweaty palms, or screams, even though nothing physical is happening. VR is even used in therapy and neurorehabilitation, reshaping the brain through immersive environments. It demonstrates both the power and the limits of perception: what matters to the nervous system is not whether something exists “out there,” but whether it feels real.

All of these realities — X-rays, ultrasonic frequencies, ultraviolet light — exist at the same time in the same space, yet no creature can detect them all. Each species lives within its own sensory bubble, or Umwelt, a term coined by biologist Jakob von Uexküll.

Cognitive scientist Donald D. Hoffman reminds us that this is not an accident. Perception did not evolve to show us the entire truth of reality; it evolved to give us just enough useful information to survive. In his words, our senses present “a simplified interface” — hiding most of what exists and offering only the slice of reality that helps us navigate daily life.

This means that what we call “the world” is only one version of a much larger, richer, and more complex reality. Our brains filter, simplify, and present just enough for us to act — but never the whole truth.

In VR, the body reacts to illusions as if they were real — proof that reality lives in the brain, not the world.

Quantum Physics: The Observer Effect

Physics, too, reveals a reality that is not absolute.

- Superposition: At the quantum level, particles can exist in many possible states at once. It is only when we observe them that they “collapse” into one definite state.

- Observer effect: In the famous double-slit experiment, particles behave like waves when unobserved but like particles when measured. Observation changes the outcome.

- Relativity: Einstein showed that even time and space are not universal constants but depend on the observer’s frame of reference.

These findings suggest that reality is not a fixed backdrop. Like perception, it is relational—shaped by the act of observing.

Reality as Interaction

When we place neuroscience and physics side by side, a striking parallel emerges. Just as the brain collapses ambiguous sensory signals into a single interpretation, quantum particles collapse possibilities into a definite state when observed. Both reveal that observation is not passive — it is participatory.

This means two people can inhabit the same physical environment yet live in different realities. Different people can find inspiration and exhaustion in the same museum. A classroom lit by fluorescent bulbs may feel neutral to some, intolerable to others. Both experiences are true because reality exists in the interaction between world and mind.

Designing Worlds, Shaping Minds

If neuroscience and physics show us that reality is not fixed but constructed, then architecture becomes one of the most powerful tools for shaping how people experience the world. Every decision — light, material, layout, proportion — guides the brain’s interpretation and therefore creates a version of reality for the user.

In this sense, architects are not only builders of structures; they are authors of realities. They select elements and compose them into environments that people inhabit, feel, and remember. A cathedral, a classroom, or a hospital corridor each generates a different reality — not because the bricks change, but because of how minds interact with them.

The challenge, then, is not simply to create a functional or aesthetic “reality,” but to craft one that is meaningful, healthier, and richer. This means:

- Meaningful, by resonating with cultural narratives and personal associations.

- Healthier, by reducing stress, supporting well-being, and accommodating sensory diversity.

- Richer, by allowing multiple interpretations and inclusive experiences rather than imposing a single truth.

Example: In dementia-friendly hospitals, designers avoid long, identical corridors that confuse patients. Instead, colour cues, artwork, and varied landmarks help with orientation. The same corridor is experienced differently depending on whether it offers clarity or disorientation — reminding us that design choices directly shape subjective realities.

Your version of reality is your brain’s interpretation of sensory data, a kind of predictive model based on experiences.

Conclusion: The Power of Subjectivity

From Plato’s cave to the halls of the Louvre, from neural circuits to X-rays and quantum fields, one lesson emerges: reality is not a fixed object waiting to be seen, but a dance between the world and the observer.

The true masterpiece is not the canvas or the building alone — it is the living multiplicity of realities that arise when we perceive them. And in embracing this, architecture gains its deepest responsibility: to design not just for one truth, but for many.

What kind of reality do you want to create?

References

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Anchor Books.

Locke, J. (1690/1998). An essay concerning human understanding (R. Woolhouse, Ed.). Penguin Classics. (Original work published 1690)

Maguire, E. A., Gadian, D. G., Johnsrude, I. S., Good, C. D., Ashburner, J., Frackowiak, R. S., & Frith, C. D. (2000). Navigation-related structural change in the hippocampi of taxi drivers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(8), 4398–4403. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.070039597

Seth, A. K. (2021, April 1). The neuroscience of reality. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-neuroscience-of-reality/

Ulrich, R. S. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224(4647), 420–421. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6143402

Wheeler, J. A., & Zurek, W. H. (Eds.). (1983). Quantum theory and measurement. Princeton University Press. (For the observer effect and superposition debates)

Wertheimer, M. (1923/1938). Laws of organization in perceptual forms. In W. D. Ellis (Ed.), A source book of Gestalt psychology (pp. 71–88). Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Original work published 1923)

The Interface Theory of Perception. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26384988/