Have you ever seen how scientists design mazes for rats?

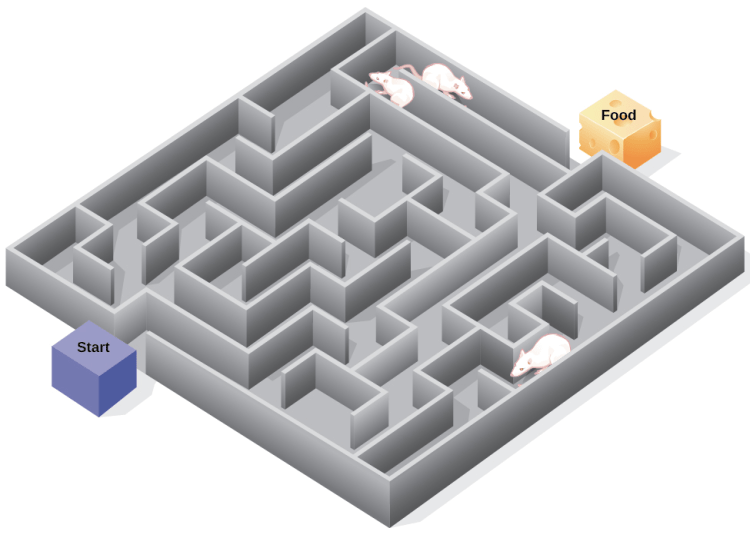

Scientists use mazes to study how small changes in an environment alter behaviour. Light levels, corridor width, or the placement of a reward can nudge an animal toward caution, curiosity, or approach. Tests such as the Social Interaction Test reveal a simple lesson: environment shapes behaviour.

Illustration of a maze used in rat behavioural tests, highlighting how environmental design influences animal behaviour.

This principle extends beyond the laboratory. Architects and urban planners design our “mazes”—cities, schools, hospitals, and homes. Every street and every building become a lived maze that influences our emotions, thoughts, and actions. The relationship is cyclical: environment shapes behaviour, and behaviour, in turn, reshapes environment.

The rat behavioural test was created in the 1970s and is still useful in studying social anxiety and how anxiety-reducing and anxiety-causing drugs work.

This master-planned community illustrates how urban design can work like a maze: the arrangement of roads, blocks, and clusters of buildings sets the conditions for how residents move, meet, and interact. Just as a laboratory maze channels a rat’s behaviour, a master plan channels human behaviour—whether towards walkability, social life, or isolation.

From lab to city — the working analogy

Though animal testing raises ethical concerns, rats remain valuable models thanks to their intelligence, social complexity, and neurological similarities to humans. What a maze does for a rat, a street network does for us. The cues are subtler, the system more complex, but the mechanisms of navigation are shared.

Both mazes and cities require inhabitants to develop cognitive maps based on spatial learning and memory. Layouts—whether a grid or irregular pattern—shape the strategies used to move through them.

The difference lies in scale and motivation. A maze is a controlled environment designed to test specific behaviours with predetermined rewards. A city is open, layered, and dynamic, where human movement is driven by diverse needs and desires. Still, the analogy shows that fundamental principles of spatial cognition link the laboratory and the street.

Designed in the mid-1950s by Minoru Yamasaki as a model of efficient public housing, the celebrated high-rise complex slid into vacancy and disrepair in less than two decades. Its implosions became a turning point: the collapse of architectural determinism and a wake-up call for environmental psychology and community-centred design. Shelter was provided; belonging was not.d design. Shelter was delivered; belonging was not.

When behaviour is overlooked — Pruitt-Igoe

The Pruitt–Igoe housing project in St. Louis is a stark example of what happens when design ignores behaviour. Conceived in the 1950s for efficiency, the project featured repetitive towers and stripped-down communal spaces. The architecture provided shelter but failed to foster a sense of belonging. The result was alienation and conflict, leading to its demolition within two decades.

Pruitt-Igoe became a symbol of modernism’s blind spot: the belief that form and function alone could engineer social outcomes. This failure led to a reckoning, shifting the focus in architecture and urban planning toward environmental psychology and the understanding that people are not passive recipients of their environment. Design doesn’t control behaviour; it channels it.

Opened in 2016 and designed by Ian Ritchie Architects, the SWC integrates neuroscience, behaviour, and machine learning research in a building conceived to shape the way science itself is done. Open-plan laboratories and shared write-up spaces foster collaboration across disciplines; quiet, enclosed zones support concentration; and circulation routes double as informal meeting places. More than a container for science, the centre is a case study in how architecture can deliberately change behavioural patterns to enhance creativity and productivity.

When behaviour is embraced — the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre

In contrast, the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre at University College London was designed with behaviour in mind. Its purpose is neuroscience, and its instrument is architecture. Open-plan laboratories and shared write-up zones encourage informal exchange, while quiet rooms support focused work. Even circulation routes are designed as social spaces rather than just hallways.

This building doesn’t just house research; it deliberately elicits the patterns of conversation, concentration, and collaboration that research needs. This demonstrates that productivity is not just a policy outcome; it is, in part, a design outcome.

The Goal: Designing a Legible Human Experience

The insights from behavioural studies in controlled mazes can help architects and planners better predict and guide pedestrian flow in the urban environment. By understanding how we respond to factors like path complexity, landmarks, and visibility, we can design cities that are intuitive, legible, and user-centric.

The ultimate goal isn’t to create a city that functions like a maze, but to learn from the maze’s lessons in spatial cognition. The urban designer’s challenge is to apply these controlled insights to the dynamic, uncontrolled urban environment. A perfectly logical grid may appear clear from above but can feel like a monotonous labyrinth for a person on the ground.

By focusing on how humans form mental maps and respond to their surroundings, we can design spaces that foster exploration, reduce anxiety, and create a legible, emotionally resonant, and dynamic experience for their inhabitants. The shift is from simply constructing a functional machine to orchestrating a more intuitive and meaningful human experience.

Next time you navigate your city, consider the subtle ways its design is influencing you.

References

The Cognitive Mapping Process: How People Mentally Represent Space. https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/architectural-community/a13408-the-cognitive-mapping-process-how-people-mentally-represent

Advice on use of the forced swim test (accessible). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/advice-on-the-use-of-the-forced-swim-test/advice-on-use-of-the-forced-swim-test-accessible#:~:text=3.3.,.%2C%202013%20(rats)).

The Impact of Architecture on Human Behaviour. https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/architectural-community/a14009-the-impact-of-architecture-on-human-behavior/

Latent Learning. https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/lumenpsychology/chapter/reading-cognition-and-latent-learning/

Ritchie Studio. (2016). Sainsbury Wellcome Centre for Neural Circuits and Behaviour, UCL. https://www.ritchie.studio/projects/sainsbury-wellcome-centre/ellcome-centre

Gifford, R. (2007). The Consequences of Living in High-Rise Buildings. Architectural Science Review, 50(1), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.3763/asre.2007.5002