Light shapes life, time, and architecture.

It doesn’t merely reveal spaces — it builds them. Long before electricity, fire, or glass existed, there was already an architecture guided by light: the sun tracing its way across stones, openings, and shadows. Nothing has changed — except how little we still talk about it.

Light has been recognised since the earliest civilisations as an essential force for life. Long before science explained its nature, humans intuitively understood that light not only enables sight but sustains existence. Today, we know this with certainty: without light, there is no health, no biological balance, and no well-being.

Biology confirms it. Light regulates ecosystems, enables photosynthesis, influences the planet’s temperature, and organises the behaviour of most species — humans included. Our bodies are programmed to respond to cycles of light and darkness, adjusting processes such as sleep, energy, and hormonal function.

In regions close to the poles, where daylight hours change drastically between seasons, this dependency becomes evident. During long winters, vitamin D deficiency, disrupted sleep, and changes in mood are common — and in some cases, Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) appears, a form of depression linked to low sunlight exposure.

Light and Circadian Rhythm

Light is an electromagnetic wave that the brain interprets as information. Through it, we not only see the world — we organise our internal life. The human body follows cycles of roughly 24 hours known as circadian rhythms, which regulate functions such as sleep, body temperature, hormone release, and alertness. The main synchroniser of this biological clock is light.

In the morning, natural light activates the production of cortisol, the hormone that promotes alertness and concentration. As daylight fades, the body releases melatonin, which prepares us for rest. Our brains are wired to respond to this alternation of light and darkness.

When that cycle is disrupted — by a lack of windows, inadequate artificial lighting, or excessive screen exposure at night — the circadian rhythm becomes unbalanced. The result: mental fatigue, irritability, insomnia, and decreased cognitive performance.

Architecture as a Light Catcher

Natural light is the most abundant and healthy source of illumination. It regulates biological systems, enhances mood, reduces stress, and strengthens the feeling of connection with the environment. For this reason, every architectural project should begin by studying how daylight enters the space.

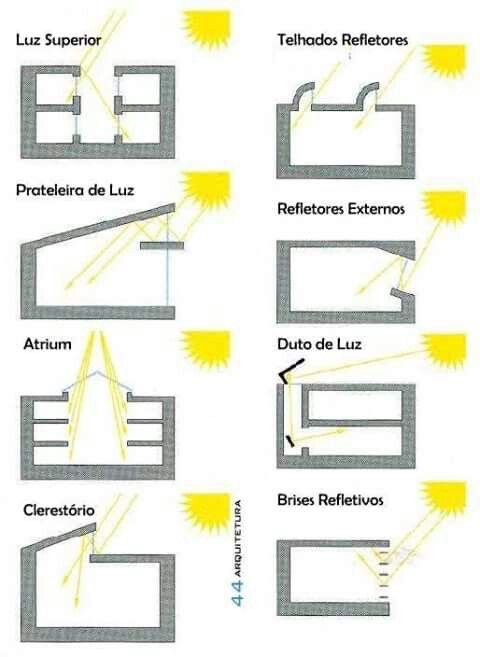

These analyses of light depend heavily on geographical location. For example, sunlight does not reach equatorial areas in the same way it does at the poles. Because of this, we have the seasons. However, throughout history, architecture has developed effective strategies to make the best use of light. Let’s have a look at some of them.

- High windows that bring light to the back of the space, creating a bright, elegant, and welcoming atmosphere that completely transforms the perception of the area.

- Bay windows protrude from the facade and their function is to capture the maximum amount of light possible, especially in winters.

- Interior patios that distribute natural light and ventilation. They are very effective in warm and Mediterranean climates.

- Skylights that allow for even overhead light. They create a sense of spaciousness and, if they can be opened, help with ventilation.

- Louvered Screens that filter direct sunlight and control glare. Additionally, they allow for ventilation and play of shadows. They are perfect for hot climates.

These solutions provide lighting, are part of ventilation, create a connection between the interior and exterior, and ultimately shape the atmosphere, generating emotions. One must consider the interplay of light, shadows, and exterior views to create positive environments. A notable example is the Church of Light by Tadao Ando, which, with a simple opening in the wall in the shape of a cross, fills the space with

Architecture and Artificial Light

It is not always possible to rely on natural light. In extreme climates, dense urban areas, or programmes such as hospitals, laboratories, and libraries, designers must create artificial lighting that substitutes, complements, or simulates daylight.

Designing artificial light is not about placing fixtures — it’s about creating conditions for visual, cognitive, and emotional well-being. Two key concepts underpin this:

1. Light intensity (lux)

This determines how much light a surface receives. Too much can be as harmful as too little — leading to visual fatigue, stress, and irritability. Adequate illumination improves performance, concentration, and safety.

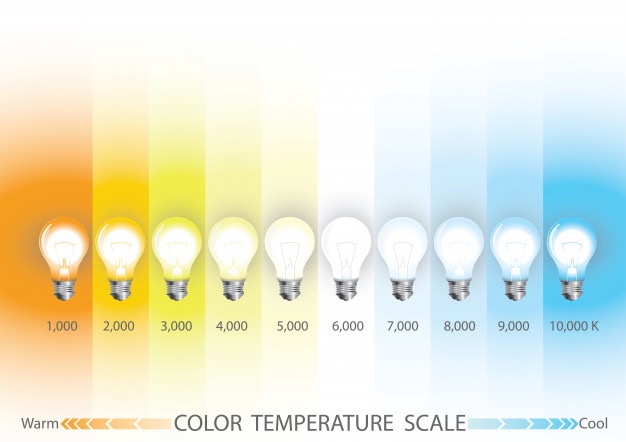

2. Colour temperature (Kelvin)

The colour temperature defines the hue of light:

| Type of Light | Kelvin (K) | Emotional Effect | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warm | 1,000–3,000 K | Relaxation | Bedrooms, lounges, restaurants |

| Neutral | 3,500–4,500 K | Natural balance | Kitchens, studios, shops |

| Cool | 5,000–10,000 K | Alertness | Offices, hospitals, workshops |

Human emotion — positive or negative — is felt more intensely under bright light.

Alison Jing Xu – (University of Toronto)

Light activates emotions. It shapes behaviour. It is not neutral.

Warm light creates intimate and welcoming atmospheres; neutral light provides clarity without distorting colours, as it most closely resembles natural daylight; and cool light, more intense and bluish, stimulates focus and activity, helping to maintain alertness and mental energy.

Light and Emotional Intensity

A study by Alison Jing Xu and Aparna Labroo at the University of Toronto found that bright light amplifies emotions — both positive and negative. Under intense illumination, participants rated pleasant stimuli as more enjoyable and unpleasant ones as more irritating.

This indicates that light doesn’t only affect visibility — it shapes emotional response. In workspaces or therapeutic environments, adjusting light intensity can mean the difference between tension and balance.

Light Layers: Designing Flexible Atmospheres

A single point of light will never be enough. The healthiest spaces work with layers of lighting:

- General light: uniform, allowing orientation.

- Task light: focused, for specific activities (reading, cooking, work).

- Ambient light: emotional, adding depth and atmosphere.

Flexibility is key. Dimmers and adjustable systems enhance comfort and enable each activity to have its own light mood.

A remarkable example is the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre in London. Each workstation there has individual lighting controls, allowing every researcher to adjust illumination to their sensory needs. Not all minds function alike; not everyone finds comfort in the same light.

Light and Human Differences

Despite its importance in our lives, light can cause discomfort, be overwhelming, or even be painful. These visual and sensory differences are essential to consider, but they deserve their development.

Some people require bright and strong lights, while others, on the contrary, prefer soft lights like those experienced by individuals with photophobia or disorders like migraine. It is key to have variety and flexibility in the lighting system so that each individual can adjust the light in their space to their specific needs without interfering or disturbing others.

Workspaces that prioritise natural daylight while also allowing users to individually adjust the artificial lighting at each desk, ensuring comfort and well-being.

Caring for Light is Caring for People

Light organises life. It regulates emotions, guides, activates, or calms. It can improve health, but it can also harm it if poorly designed. In buildings with little natural light, there should always be at least one escape space to the outside, a terrace, a patio, a garden, or a window with a real view. Light and view are human needs, not architectural luxuries.

Designing with light is not just a technical act: it is an ethical act. The way we illuminate a space determines how people will inhabit it, how they will work, how they will sleep, how they will heal, how they will learn.

Light is architecture. Light is biology. Light is emotion.

Referencias

Xu, A. J. & Labroo, A.

“Turning on the hot emotional system with bright light.”

ScienceDaily+3Carlson School of Management+3ScienceDirect+3

“Effects of colored lights on an individual’s affective impressions in visual tasks” PMC

“Effects of Light on Attention and Reaction Time: A Systematic Review” PMC

“Effects of illuminance and correlated color temperature on emotional valence and arousal in indoor environments” ScienceDirect

“Effects of blue-enriched light treatment compared to standard light treatment in seasonal affective disorder (SAD)” ScienceDirect

“Effects of Light on Human Circadian Rhythms, Sleep and Mood” PMC

“Timing of light exposure affects mood and brain circuits” PMC

“The Effect of Light on Wellbeing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis” PMC