Although official data on neurodivergence and homelessness remain limited, the available evidence suggests that neurodivergent people —particularly autistic individuals —are disproportionately represented among those experiencing housing insecurity or homelessness in the United Kingdom.

The absence of stable housing activates prolonged stress responses, with direct and lasting consequences for mental health. For this reason, the housing crisis cannot be understood solely as a social or economic issue; it must be recognised and addressed as a public health emergency.

Several studies indicate that between 12% and 18% of people accessing homelessness support services are autistic, compared to just 1–2% of the general population. This disparity is not accidental. It reflects persistent barriers in education, employment, and access to appropriately adapted services—barriers that compound vulnerability in a world largely designed for neurotypical ways of thinking, sensing, and communicating.

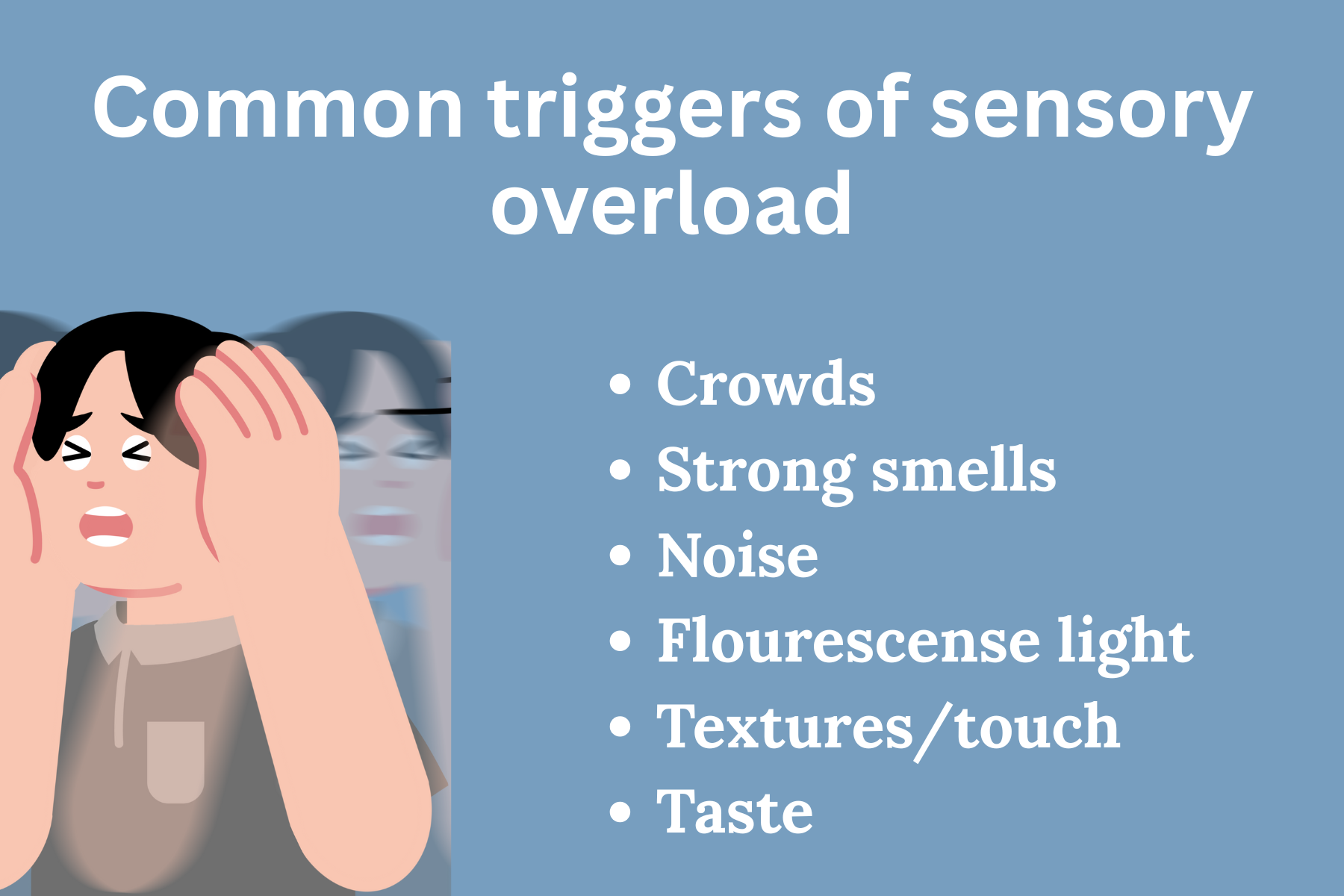

The environment is not neutral: it can intensify sensory overload. Good design facilitates sensory and emotional regulation.

Reimagining the Home: Design Recommendations for Neurodiverse Lives

Designing for neurodiversity cannot be done at a distance. Sensory, cognitive, and emotional experiences cannot be assumed—they must be listened to. For this reason, any genuinely inclusive approach must be rooted in co-creation with neurodivergent people, incorporating their voices from the earliest stages of the design process.

When we think about “home”, roofs and walls are not enough. For a space to be truly liveable—particularly for neurodivergent people—it must support sensory regulation, preserve emotional stability, and foster everyday autonomy. In the context of the current housing crisis, these considerations are not optional enhancements; they are fundamental to wellbeing.

It is equally important to emphasise that many of these strategies do not require large budgets. Sound-absorbing textiles, visual cues and labelling, spatial order, and control over colour and light intensity are low-cost, high-impact interventions.

For this very reason, neuroinclusive design is not a luxury reserved for private housing. It is both viable and necessary in social housing, temporary accommodation, and emergency settings, where emotional stability can mean the difference between containment and collapse.

The following recommendations offer general principles that can be applied both to new homes and to the adaptation of existing spaces.

Sensory Control as a Design Principle

One of the most commonly reported challenges among neurodivergent people relates to sensory stimulation. Excessive noise, harsh lighting, or visual clutter can trigger anxiety or cognitive shutdown, while environments that are overly monotonous may undermine attention and motivation. To address this:

- Adaptable lighting: combine generous natural daylight with adjustable artificial lighting (such as dimmers), allowing intensity and colour temperature to be adapted to different activities and emotional states.

- Domestic acoustics: use materials that absorb sound—acoustic panels, thick textiles, carpets—and consider quiet zones or small retreat spaces for moments of sensory overload.

- Visual stimulus control: surfaces in soft, neutral palettes help reduce unnecessary stimulation without stripping spaces of character. Accents of colour can be reserved for areas of focus or creative rest.

Together, these strategies allow individuals to modulate their sensory exposure, reducing fatigue and reinforcing a sense of control over their environment.

Clearly Defined Zones and Spatial Transitions

Open-plan layouts have become a dominant design trend. However, for people who process information differently, clearly defined zones with gentle transitions offer predictability and structure—both essential for emotional regulation and everyday routines.

Spaces for work, rest, or play can be defined through furniture placement, changes in texture, or variations in lighting, rather than through unnecessary walls. This approach provides clear perceptual cues without fragmenting the home.

Creating “soft thresholds”—such as small alcoves, subtle colour shifts, or rugs—helps signal changes in spatial function and supports internal orientation within the home.

Personalisation and Individual Control

Everyone benefits from the ability to adjust their environment to changing needs—but this capacity is especially important for neurodivergent people:

- Accessible controls: light switches, blinds, or curtains that can be easily operated from the usual position of use.

- Adjustable furniture: elements with flexible heights, movable coat racks, or adjustable tables that can adapt to different tasks and personal preferences.

- An optional sensory corner: a space that can shift between a low-stimulation retreat and a more activating area, depending on the time of day or emotional state.

This principle reflects a core idea of neurodesign: there is no single “best” environment, only spaces that allow individuals to adapt their surroundings to their own needs.

Nature Indoors (Biophilia) and Emotional Regulation

Integrating natural elements—such as plants, warm textures, and views to the outdoors—has been shown to support both emotional and cognitive regulation in domestic environments.

This is not about excessive decoration, but about fostering sensory connections with nature that reduce perceptual tension and encourage states of calm. These can range from something as simple as a potted plant by a window to the use of materials like wood and stone in interior finishes.

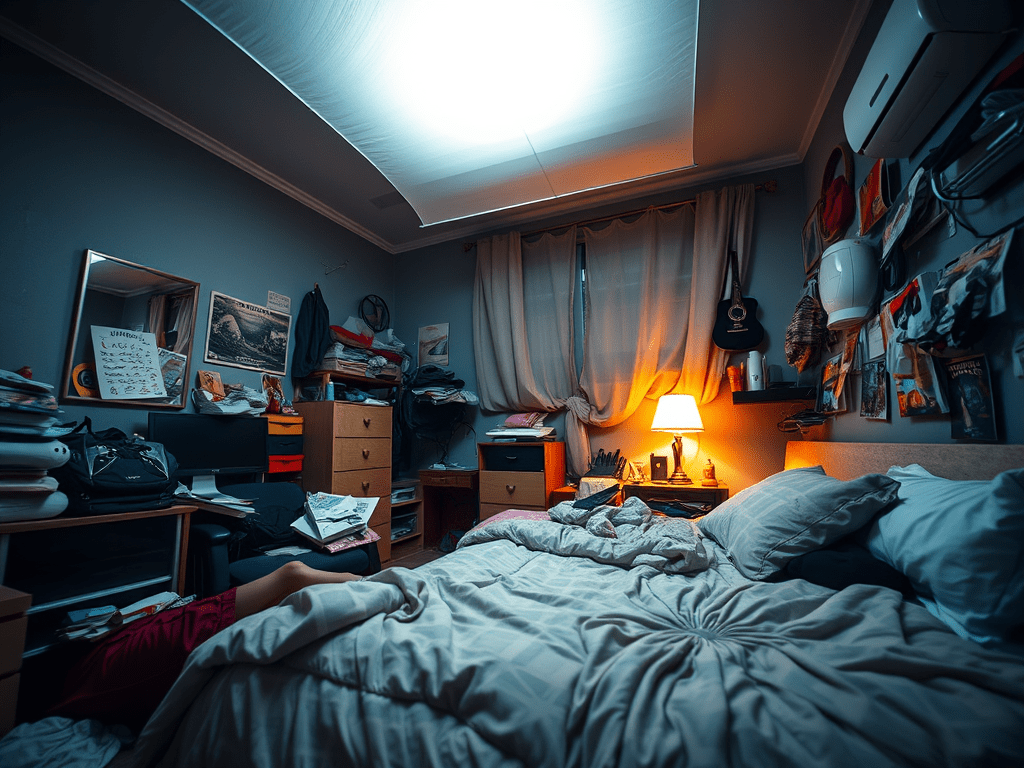

Organisation as Cognitive Support

Clutter can act as a powerful trigger for perceptual overload. For this reason, intuitive and visible storage solutions help reduce anxiety and support everyday routines:

- Open shelving for frequently used items.

- Organisers with clearly defined compartments for clothes, toys, or tools.

- Gentle visual cues—such as labels or colour coding—to make it easier to identify storage locations within cupboards or drawers.

This approach is not a trend. It is a way of shaping the environment so that the brain can anticipate, recognise, and locate, functions that lie at the core of daily life.

Kitchen (top left): Natural light and clear organisation help reduce sensory overload in frequently used spaces.

Living area (top right): Clearly defined zones and gentle transitions support emotional regulation and predictability.

Bedroom (bottom left): Warm lighting and tactile materials promote rest and calm.

Bathroom (bottom right): Soft textures, visual order, and indirect lighting help reduce intense sensory stimuli.

A home that supports sensory regulation is not a luxury; it is a matter of health.

Towards an Architecture that Respects Cognitive Diversity

The housing crisis demands more than rapid fixes or minimum standards of habitability. It calls for an architecture capable of understanding how the human mind functions under conditions of stress, change, and prolonged uncertainty.

For neurodivergent people, cumulative challenges in education, employment, and social life significantly increase the risk of housing instability. When systems fail—when the environment does not regulate, orient, or support—the home ceases to be a refuge and becomes an additional source of sensory overload and emotional strain.

Designing neuroinclusive homes does not mean creating “special” spaces. It means recognising that not everyone processes the world in the same way. It means designing with, not merely for, those who inhabit these environments. The principle championed by the community itself—“nothing about us, without us”—is not a symbolic slogan, but a practical guide to creating spaces that genuinely work.

In the context of a global housing crisis, it is equally important to emphasise that many of these strategies are low-cost and high-impact. Acoustic textiles, lighting control, visual order, clear spatial zoning, and simple perceptual supports can be integrated into social housing, temporary accommodation, and emergency settings, where emotional stability is fundamentally a matter of public health.

Alongside spatial decisions, accessible and discreet technologies—such as adaptive lighting systems or integrated visual reminders—can further reduce cognitive load and support everyday autonomy when used thoughtfully, without adding unnecessary complexity.

For architects, urban designers, and policymakers, technical frameworks already exist to support this shift. The PAS 6463:2022 standard, developed in the United Kingdom, provides clear and applicable guidance for designing environments that account for cognitive and sensory diversity through a rigorous and practical lens.

Recommended Readings

Design for the Mind. Neurodiversity & the Built Environment — PAS 6463.

Homelessness and disability in the UK.

Around 90% of autistic adults over 40 are undiagnosed in UK, researchers find