The Palace of Versailles, one of the most imposing royal residences in Europe, was conceived as a political instrument. Under the reign of Louis XIV, France sought to consolidate absolute power after decades of internal unrest. Versailles became the ideal stage upon which that ambition could be made visible.

To prevent conspiracies and uprisings, the king chose to distance the nobility from Paris and concentrate them within a carefully designed environment that allowed him to supervise and control the aristocracy continuously. Physical proximity to the monarch became both privilege and dependency: to be near the king meant retaining influence and favour. For that reason, the nobles agreed to relocate.

Daily life at court was transformed into ritual. The king’s rising, his meals, even his retirement for the night were public acts. Versailles was not designed first and foremost as a home, but as a stage — a political theatre in which absolutism revolved around the figure of the Sun King.

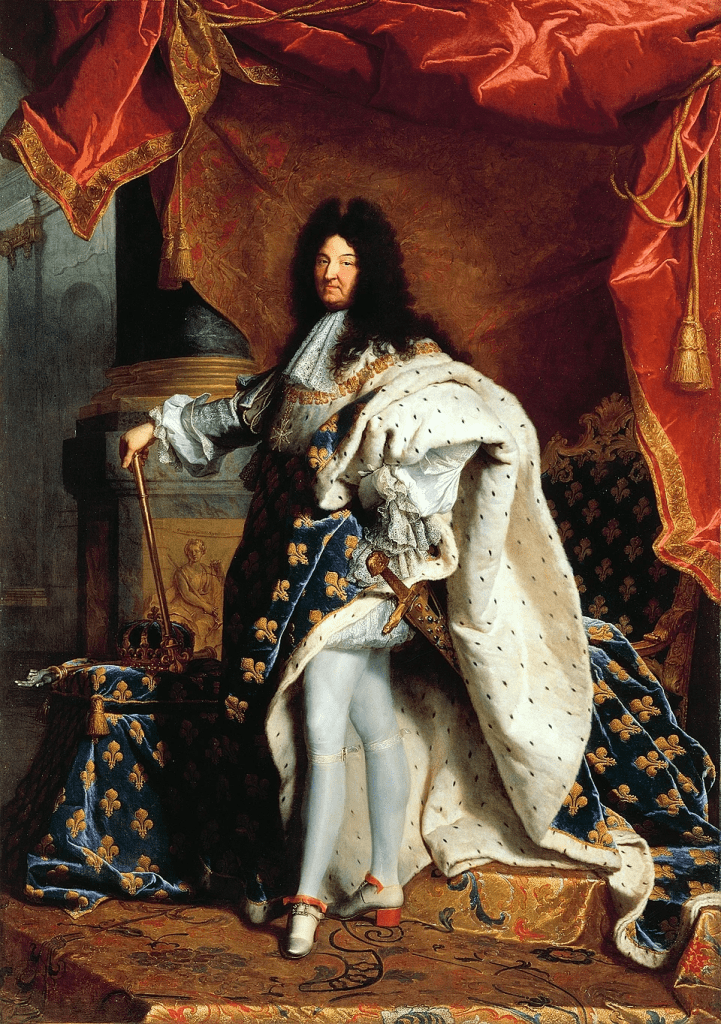

Portrayed by Hyacinthe Rigaud (1701) and represented in an equestrian sculpture by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1677). Painting and sculpture do not merely depict the monarch; they construct the visual language of absolutism — body, gesture, and theatricality transformed into instruments of political authority.

A Political Stage, Not a Home

The palace’s grandeur stemmed from the transformation of Louis XIII’s former hunting lodge in the 1660s. Over more than fifty years, architects, and landscape designers expanded and redefined the complex, turning it into an architectural laboratory devoted to the glorification of the monarch.

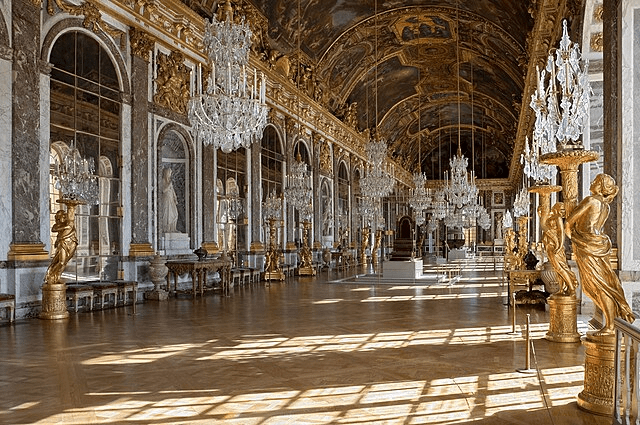

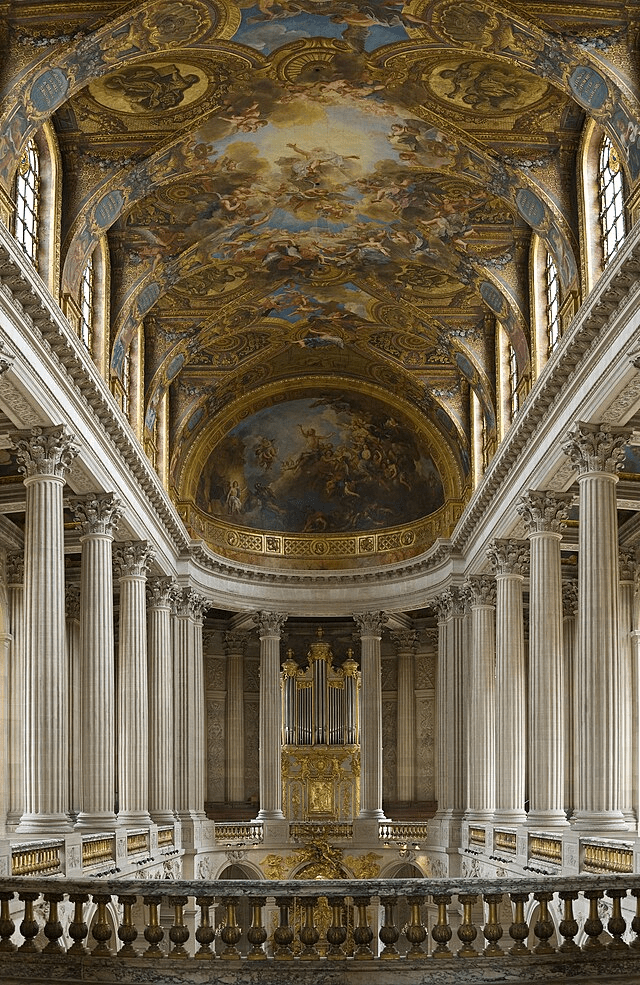

Its monumental character is expressed through rigorous axial planning, the succession of state rooms arranged enfilade, the celebrated Hall of Mirrors, and gardens that appear to project royal authority towards the horizon. Scale did not merely impress; it organised social space. Each visual axis reinforced hierarchy. Each perspective symbolically extended the king’s authority.

Luxury was not improvised. To sustain the project, specialised manufactories and workshops were established to produce tapestries, large-format mirrors, furnishings, gilded ornamentation and marquetry. Versailles also functioned as an early form of industrial organisation, mobilising resources, craftsmanship and technology on a scale unprecedented in seventeenth-century Europe.

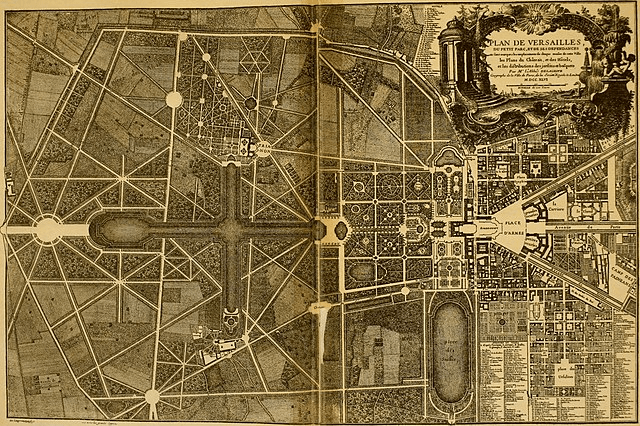

The cartographic representation reveals the rigorous axial planning and territorial geometry that extended the palace’s order into the surrounding landscape, transforming the territory into a symbolic extension of royal power.

The composition reveals the strict axial structure of the complex and its relationship with the surrounding urban fabric: the palace does not stand in isolation; it organises the territory. From this perspective, it becomes clear how architecture and landscape were conceived as a geometric extension of political power.

Living in Splendour: The Everyday Experience

The memoirs of the Duc de Saint-Simon and the letters of Madame de Sévigné describe not only dazzling luxury, but an intense, ritualised and demanding courtly life. Versailles impressed the visitor; living there was another matter entirely.

Unstable thermal comfort. The grand state rooms, conceived to magnify royal power, were difficult to heat in winter and could become stifling in summer. Monumental scale, effective as political symbolism, did not necessarily support thermal wellbeing.

Hygiene challenges. With a vast population and almost non-existent sanitary infrastructure, waste management was precarious, making unpleasant odours, disease, and infestations a constant reality. Indeed, due to lice, many chose to shave their heads so that their wigs could be boiled to eliminate nits.

Noise, continual building works and overcrowding. For decades, Versailles remained under constant expansion. Scaffolding, dust and continuous movement formed part of daily life. High density generated persistent friction.

Lack of privacy. Life at court meant constant exposure. Protocol transformed intimate acts into public events. Proximity to the monarch was a privilege, but also a form of surveillance.

If the Hall multiplies light and the image of power through reflection and repetition, the Chapel lifts the gaze through verticality, allegorical painting and music. Two distinct yet complementary spaces: one horizontal and ceremonial, the other ascending and liturgical. In both, architecture does more than organise space; it directs perception and constructs authority through scale, rhythm and sensory experience.

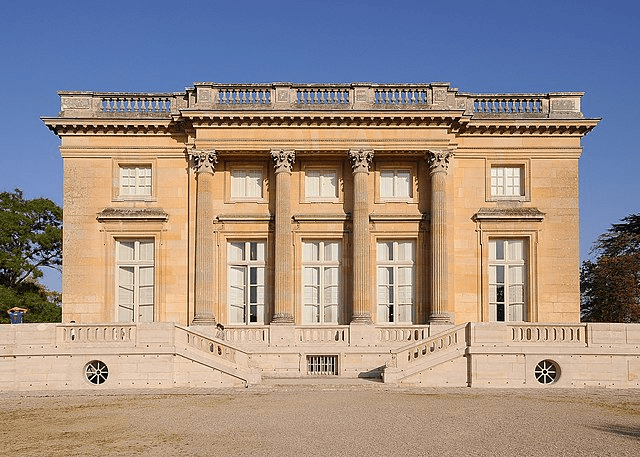

The Petit Trianon: Marie Antoinette’s Retreat

Decades later, Marie Antoinette grasped something profoundly human: she needed an environment different from the grand palace. Magnificence alone was not enough to sustain everyday life.

She chose the Petit Trianon, a small palace set within the gardens of Versailles, where she could withdraw with a reduced circle of ladies and attendants. There, the scale was more contained, the protocol less oppressive and the ceremonial pressure diminished.

The Petit Trianon offered what the main palace could not guarantee: greater privacy, lower social density and a more moderate sensory load. In an environment designed to be seen and judged, that retreat represented a form of regulation.

The gesture reveals a truth that transcends its time: even at the heart of absolute splendour, human beings do not require marble, gold, or mirrors to feel well. They require balance, rest, and connection.

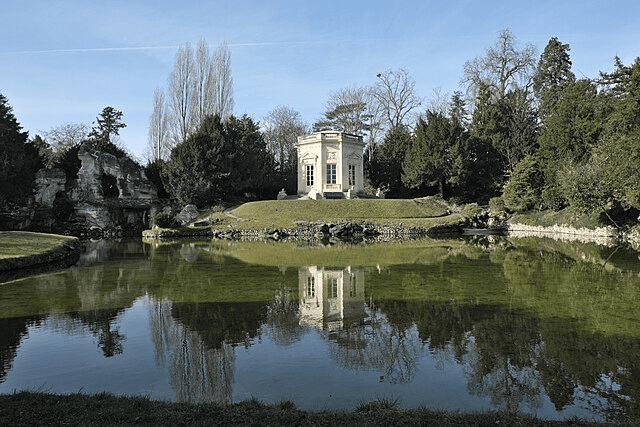

More contained in scale and classical in proportion, this small palace offered a contrast to the monumental character of the main complex. Its symmetrical composition and closer relationship with the gardens suggest an architecture conceived less for public display and more for retreat and intimacy.

More intimate interiors and simpler furnishings stand in contrast to the grandeur of the main palace. The gardens, quieter and allegorical in character, create an environment conceived for retreat and relaxation.

From Monumentality to Human-Centred Design

The Palace of Versailles is an unquestionable historical landmark. It fulfilled its role as a political epicentre and emblem of absolutism. Yet from a contemporary perspective — particularly through the lenses of sustainability and neuroarchitecture — its grandeur requires nuance.

Its construction involved a radical intervention in the landscape. Marshlands were drained, forests reshaped and vast resources mobilised. In the seventeenth century, ecological awareness did not exist as we understand it today; however, we now recognise that disconnection from the natural environment carries physiological and psychological consequences.

Versailles demonstrates that majesty does not necessarily translate into wellbeing. A space can be visually extraordinary and, at the same time, sensorially demanding or even hostile.

Today we understand that design cannot be evaluated solely in terms of aesthetics or symbolic representation, but must also be considered through its environmental, cognitive and emotional effects. When architecture prioritises the ego of power over the health of its occupants, it risks generating chronic tension rather than lasting comfort.

Recommended Readings

Versailles: A Biography of a Palace – Tony Spawforth. https://archive.org/details/versaillesbiogra0000spaw/page/n7/mode/2up

The Fabrication of Louis XIV – Peter Burke https://archive.org/details/fabricationoflou0000bur

The Court Society – Norbert Elias https://archive.org/details/courtsociety00elia/page/n9/mode/2up

Memoirs – Duc de Saint-Simon https://archive.org/details/memoirsofducdesa0000sain_s0f2