According to the World Health Organization (WHO), mental health conditions include mental disorders, psychosocial disabilities, and other emotional states that significantly impair daily functioning or increase the risk of self-harm.

The Crisis: Anxiety, Disconnection, and Isolation

Alfred, a 90-year-old widower from Wakefield, spent six months in near-total isolation. After losing his wife, his only human contact came from brief moments—taking out the bins or attending medical appointments. Loneliness is a major risk factor for mental health decline. It’s associated with depression, anxiety, cognitive deterioration, and cardiovascular disease.

In the UK, Age UK reports that nearly one million older adults often feel lonely—with more than 270,000 going a full week without speaking to anyone.

Mary experienced her first severe anxiety episode at 15. With counselling, she developed coping strategies and regained her confidence. But during her master’s degree at 21, a heavy academic workload, unfamiliar surroundings, and a painful breakup left her overwhelmed. The strategies that once helped her no longer worked. She became withdrawn and ashamed of needing support again.

In 2022/23, an average of 37.1% of women and 29.9% of men in the UK reported high anxiety levels—marking a rise from previous years.

Mental health is no longer a secondary concern—it’s a pressing issue that should influence how we structure our systems, shape our policies, and support one another. According to Mind UK, one in four people in the UK experiences a mental health condition each year, with anxiety and depression being the most common.

A Holistic Approach

The responsibility for mental health cannot rest solely on individuals. It requires systemic responses across health, education, and the built environment. Important organizations and professionals advocate for holistic care—supporting the emotional, physical, social, and even spiritual needs of people.

Essential practices include:

- Regular physical activity

- Sleep hygiene and good nutrition

- Meaningful hobbies and community engagement

- Mindfulness and stress regulation

- Strong interpersonal relationships

These are often discussed as lifestyle changes, but they depend deeply on the spaces that enable—or block—them. Designing for mental well-being means shaping environments that make these habits natural and accessible.

Globally, mental health disorders account for 1 in 6 years lived with disability. People with severe conditions die 10 to 20 years earlier than the general population. They also face a greater risk of suicide and human rights violations.

Mental Health: Urbanism, and Architecture

Although access to clinical services is fundamental, the NHS has identified some aspects that affect the quality of life and mental health of individuals. Here, we highlight those relate to the built environment, such as people who experience homelessness, insecure, and inadequate housing.

Organizations such as Public Health England and the World Health Organization (WHO) agree that factors such as social support, safe housing, contact with nature, and tranquil environments play an essential role in protecting psychological well-being.

But many of the places we inhabit—from classrooms and hospitals to housing estates—undermine mental well-being. They overstimulate, isolate, and add to emotional strain. Architecture, urbanism and mental health must be addressed together.

What was once an industrial warehouse is now a vibrant public space—a testament to how thoughtful renovation and placemaking can transform disconnection into community. Architecture has the power to either reinforce that silence—or offer new paths to connection.

Design for empathy

Architecture is not neutral. It shapes how we feel, how we heal, and how we connect. From hospitals and schools to homes and public parks, every space carries psychological weight.

Designers—whether architects, urbanists, or planners—are not just building structures. They are shaping perception, emotion, and community. In the context of a mental health crisis, their role is more urgent than ever.

The good news? Design doesn’t need to rely on guesswork. Three well-established fields provide a foundation for evidence-based design that improves mental health outcomes:

1. Environmental Psychology: Design and Human Behaviour

Environmental psychology studies how our surroundings affect human thoughts, emotions, and behaviours. Originally developed in response to urbanisation’s negative effects, this field explores how noise, pollution, and spatial layout affect mood and interaction.

Pioneers like Kurt Lewin and Roger Barker revealed how physical settings shape behaviour. Today, this science informs architectural strategies such as:

- Sociopetal spaces that encourage connection

- Defensible space to increase perceived safety

- Community-centred layouts

One powerful case: New York’s High Line. Once a derelict rail line, it was transformed into a green urban corridor that supports biodiversity, reduces stress, and restores public life—proving how mental health and architecture can be positively linked.

Once an abandoned railway, the High Line in New York is now a vibrant green corridor that reconnects people with nature and each other. It’s a powerful reminder that thoughtful urban design can transform disused infrastructure into spaces that promote well-being, social connection, and collective renewal.

2. Biophilic Design: Nature as a Healing Element

Biophilic design builds on our natural affinity for the outdoors. By reintroducing nature into the built environment, it fosters psychological restoration, emotional regulation, and cognitive clarity.

It offers measurable benefits:

- Reduces cortisol and heart rate

- Improves mood and concentration

- Activates the parasympathetic nervous system

Core biophilic elements include:

- Visual nature: windows, plants, water features

- Natural materials: wood, stone, organic forms

- Biomorphic patterns: shapes found in trees or shells

- Light and airflow: mimicking circadian rhythms

- Refuge and prospect: areas that feel both sheltered and open

Research from Stephen Kellert, Judith Heerwagen, and Terrapin Bright Green shows that biophilic design fosters long-term mental well-being, especially in dense urban environments.

A vibrant riverside promenade in London, showcasing the interaction of people with nature and urban architecture, highlighting the importance of public spaces for mental well-being.

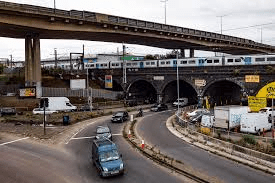

Prime example of infrastructure designed for cars, not people. It severs neighbourhoods, discourages walking, and fosters disconnection. Spaces like this highlight how urban design can undermine community, well-being, safety and mental health.

3. Neuroarchitecture: Designing with the Brain in Mind

Neuroarchitecture connects architectural form with neuroscience. It studies how factors like spatial geometry, lighting, sound, and materiality influence brain function, mood, and behaviour.

Thanks to advances in brain imaging, we now know that built environments can either support or undermine neurological health. For example:

- Poor way finding increases stress

- Harsh lighting triggers discomfort

- Certain spaces activate fear or confusion

- Calm, regulated environments improve emotional stability

Pioneers like J.P. Eberhard and Fred Gage, along with the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture (ANFA), are leading this field.

Designs grounded in neuroarchitecture can:

- Reduce cognitive load

- Soothe anxiety through sensory regulation

- Support neurodivergent users

- Reinforce memory, pleasure, and social bonding

This isn’t speculative design—it’s architecture aligned with the brain.

Neurotectura’s Commitment to Mental Health in Architecture

If we truly aim to improve mental health, we must take our environments seriously.

From homes and hospitals to schools and streets, every built space has the power to either burden or elevate us. Mental health in architecture is not a luxury—it’s a responsibility.

At Neurotectura, our central mission is to contribute to mental well-being through design. We lead with the science of neuroarchitecture, while integrating the wisdom of environmental psychology and biophilic design. Together, these disciplines help us craft spaces that are not only functional—but healing, inclusive, and life-enhancing.

We believe architecture should do more than shelter—it should support. That’s why we’re committed to sharing knowledge, building community, and advancing design that makes people feel safe, calm, and connected.

Because when we design with empathy, evidence, and imagination, we don’t just build better spaces—we build better futures.

What could your home, school, or street look like if it were truly designed for emotional well-being?

References

- Age UK. (n.d.). Loneliness—Facts and statistics. Retrieved from https://www.ageuk.org.uk

- Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture (ANFA). (n.d.). Homepage. Retrieved from https://www.anfarch.org

- Eberhard, J. P. (2009). Brain Landscape: The Coexistence of Neuroscience and Architecture. Oxford University Press.

- Gage, F. H. (2003). Neurogenesis in the adult brain: Human brain architecture and new neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(19), 10809–10811. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1934518100

- Kellert, S. R., Heerwagen, J. H., & Mador, M. L. (Eds.). (2008). Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Wiley.

- Lewin, K. (1936). Principles of Topological Psychology. McGraw-Hill.

- Mind. (n.d.). Mental health facts and statistics. Retrieved from https://www.mind.org.uk

- National Health Service (NHS). (n.d.). Mental health services. Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2023). Anxiety levels in the UK: 2022 to 2023. Retrieved from https://www.ons.gov.uk

- Public Health England. (2019). Mental health: Prevention and promotion. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/mental-health-prevention-and-promotion

- Terrapin Bright Green. (2014). 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design: Improving Health and Well-Being in the Built Environment. Retrieved from https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/reports/14-patterns

- World Health Organization. (2022). Mental health. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health

- Understanding the crisis in young people’s mental health https://www.health.org.uk/features-and-opinion/blogs/understanding-the-crisis-in-young-people-s-mental-health#:~:text=More%20recently%2C%20the%20COVID%2D19,transition%20from%20education%20to%20employment.