Throughout history, architecture has been described in many ways—sometimes as pure art, other times as a fusion of art and technology. But what if we saw it differently? Not just as shelter or infrastructure, but as the creation of realities.

Unlike video games or virtual reality, this is not about digital simulations. It is about tangible, three-dimensional environments. Concrete, glass, timber, and stone become the tools through which architects bring worlds into being.

What’s Reality?

Reality can be defined as the state of things as they exist—encompassing the physical world, its fundamental building blocks, and the social and cultural conditions we live in, regardless of our fantasies or desires.

Yet, our access to this reality is always mediated through perception. Our senses and brains filter, interpret, and construct the world we experience. This blurs the line between what actually exists and what merely appears, making reality both objective in its foundations and subjective in how it is lived.

“The world we experience comes as much from the inside-out as from the outside-in.”

Anil Seth — Professor of Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience

Why Reality Is Not What It Seems

Over two thousand years ago, Plato imagined prisoners chained inside a cave, mistaking shadows for reality. Only when one prisoner stepped into the sunlight did he understand that what they had seen was not the world itself, but a distorted projection of it.

Plato was closer to the truth than he could have known. Our brains receive only a fraction of the world’s signals, leaving most of the real world hidden. Human eyes are tuned to a band of visible light—just 400–700 nanometres—while countless other wavelengths remain invisible.

Each species perceives the world differently through its unique senses: dogs, with millions of olfactory cells, track prey invisible to us; bees detect colours beyond our imagination to navigate and communicate; and bats hear ultrasounds of up to 200 kHz to fly through the dark. All of them far surpass human abilities.

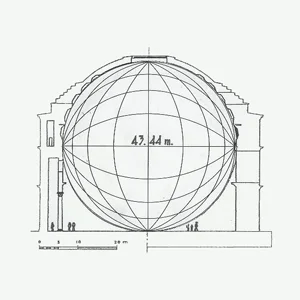

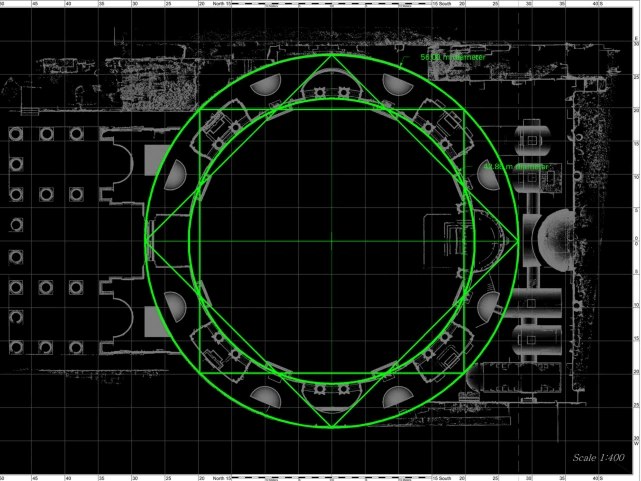

The Pantheon, or temple of all gods, features a vast concrete dome with a central opening, its only source of natural light. The effect of the incoming light functions like a giant sundial, creating dramatic effects within the interior.

Architects have long understood the limits of perception. With only fragments of light and material, they craft illusions of infinity. The Pantheon in Rome is a masterclass in this art. Its vast dome, pierced by a single oculus 24 feet (7.32 m) wide, funnels daylight into the interior like a cosmic clock. As the sun shifts, the beam of light sweeps across the walls and floor, transforming a solid space into a theatre of time itself.

From fragments of illumination, an entire universe is constructed. Visitors often describe being overwhelmed to the point of tears — not by what the Pantheon “is,” but by what it makes them perceive: a reality that feels boundless, sacred, and transcendent.

As Donald Hoffman’s Interface Theory of Perception suggests, our senses did not evolve to reveal truth but to guide survival, offering us a simplified “interface” to reality. Neuroscientist Anil Seth echoes this view, calling perception a “controlled hallucination”: not a passive recording of the world, but the brain’s ongoing best guess—shaped by expectation, memory, and culture—about what lies beyond the senses.

Physics confirms the same: Einstein’s relativity shows that even time and space depend on perspective, while the quantum world reveals particles collapsing into certainty only when observed. Reality, then, is not fixed but emerges through interaction and observation.

When Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum opened on Fifth Avenue, neighbours denounced it as a “monstrosity” clashing with Manhattan’s grid. Today it is celebrated worldwide as a masterpiece and symbol of New York, though its popularity still burdens residents with noise and crowds.

“The whole thing will either throw you off your guard entirely or be just about what you have been dreaming about.”

Frank Lloyd Wright – on the Guggenheim Museum

Multiple Realities

If perception is influenced by biology and experience, a unified reality is unattainable, resulting in diverse interpretations of events and various subjective realities instead of a single truth.

The Guggenheim Museum in New York exemplifies how architecture influences individual experiences, highlighting that elements like the spiral, acoustics, and light are subjectively interpreted by each person.

- A student architect might marvel at the building as a technical masterpiece of form and material, while an art historian could focus on its place in the intellectual history of design.

- A tourist, by contrast, may find its spirals confusing or disorienting, struggling with ramps that feel either playful or exhausting depending on the body that walks them. For some visitors, echoes in the rotunda are a distracting intrusion; for others, barely noticed.

- Meanwhile, residents often see the museum as both a cultural anchor that has revitalised their neighbourhood and a source of nuisance through noise and crowds.

The museum, therefore, is not one monolithic “reality.” It is many, each shaped by the interaction of architecture and perception. This is the essence of why some people love it and others hate it, with both experiences equally valid.

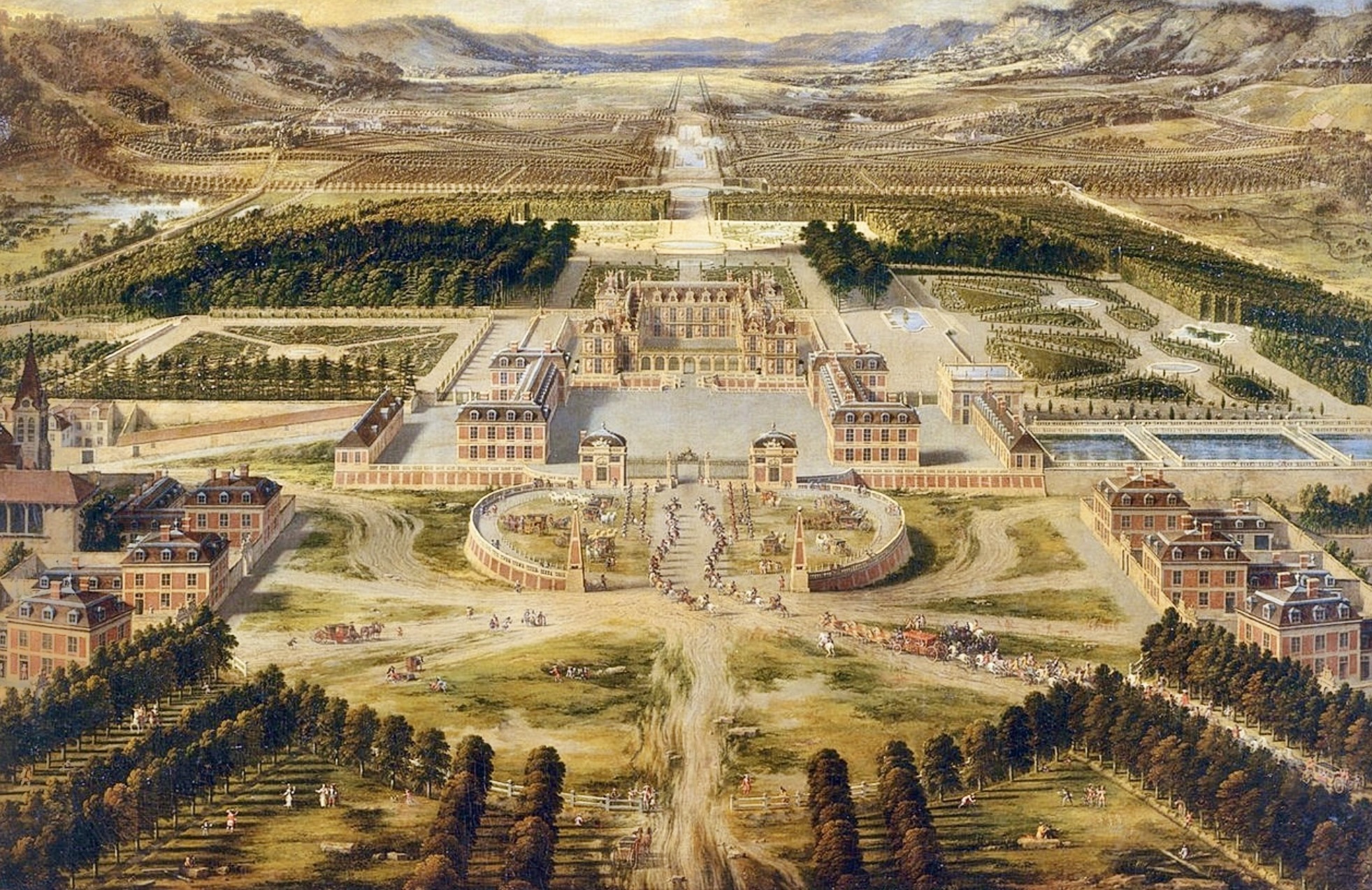

Versailles was more than a royal residence. It was a stage for absolute power. Every axis, vista, and garden path was designed to direct the eye back to the king, shaping a political reality of hierarchy and control that visitors could not escape.

Architecture as the Craft of Realities

If perception creates reality, then architecture—by shaping perception—creates realities too. The built environment is one of the most powerful forces in human experience. Architecture is never neutral: it modulates, filters, and funnels perception.

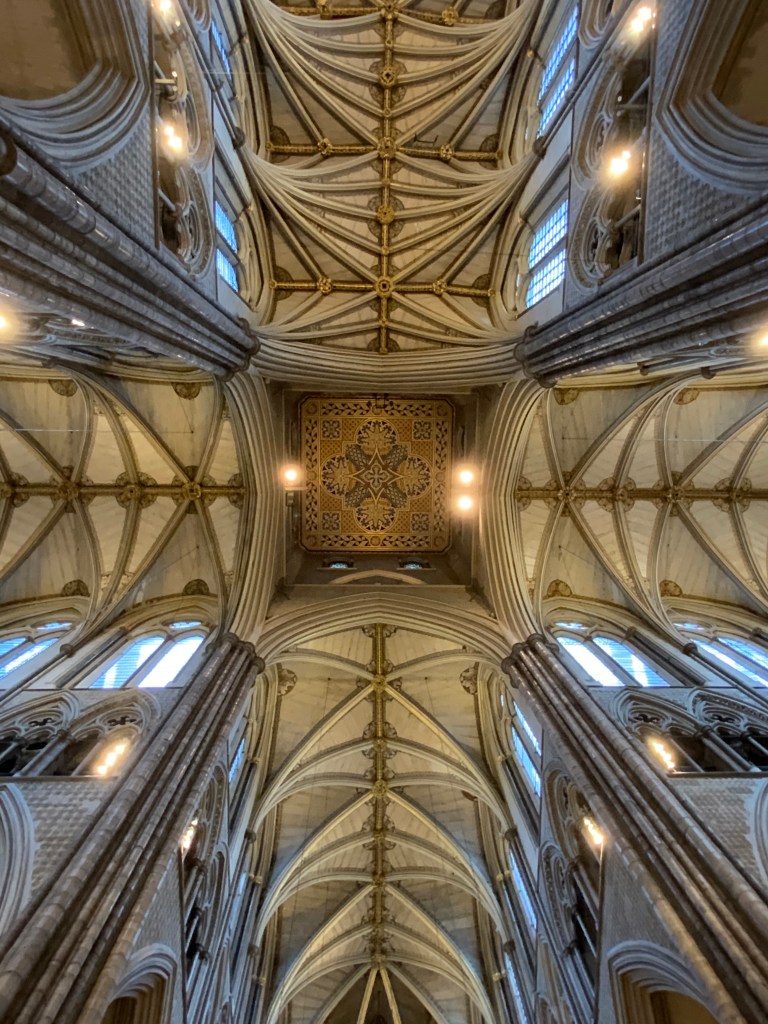

History proves it. The Palace of Versailles imposed political order, Gothic cathedrals inspired awe, the Pantheon conjured the cosmos, and the Guggenheim divides its public. In each case, the architecture scripted perception—and with it, reality.

Commissioned by Henry III, the Abbey became a stage for coronations and burials, a “Bible in stone” for the illiterate, and a monument of civic pride. Its pointed arches lifted the gaze toward heaven, while its cruciform plan embodied the Christian cosmos. Inside and out, it scripted a sacred reality designed to unite, teach, and awe.

Notre Dame’s stained-glass windows were not decoration but doctrine. They cast coloured light as symbols of divine truth and immersed the faithful in a theocentric reality: not the natural world, but the world as revealed by the Church, where saints, kings, and believers alike occupied a divine hierarchy.

The same happens today. In a hospital, a corridor can reassure with daylight and landmarks—or disorient with monotony. In a school, playful spaces can spark collaboration—or rigid partitions can stifle it. In a city, a sunlit square can invite connection, while a dark alley provokes anxiety. Every design decision is a choice about how reality will be lived.

The Responsibility of Creation

From Plato’s cave to modern neuroscience and quantum physics, one lesson is clear: reality is not uncovered — it is co-created.

Psychology shows a strong and consistent link between perceived reality and behaviour — even when those perceptions are partial, biased, or false. In other words: we become what we believe; we are what, we think, is real. Perception is not passive; it is the engine that drives thought, behaviour, and society itself.

This places a profound responsibility on architects. We are not merely builders of objects but shapers of perception, emotion, and meaning. The environments we design can reinforce alienation, anxiety, and hierarchy—or they can cultivate empathy, connection, and dignity.

Some projects already embody this shift. The impersonal, echoing wards of modernist hospitals have given way, in places like the Maggie’s Centres in the UK, to spaces of warmth, intimacy, and light. These centres show that architecture does more than house care — it becomes care, shaping realities of healing rather than despair.

The real question is no longer whether architecture creates realities. The questions we must face are:

What realities are we bringing into being — and for whom?

And how do we design futures that are more inclusive, empathetic, and sustainable?

References

The Neuroscience of Reality https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-neuroscience-of-reality/

How does consciousness happen? Anil Seth speaks at TED2017. https://blog.ted.com/how-does-consciousness-happen-anil-seth-speaks-at-ted2017/

A phenomenological framework for describing architectural

experience. https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/95941/1/Cork%20%28distribute%29.pdf

The Guggenheim: Critical Response https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/frank-lloyd-wright/guggenheim-critics

Psychology today: 3 Ways Your Beliefs Can Shape Your Reality. https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/in-love-and-war/201508/3-ways-your-beliefs-can-shape-your reality