If someone were to ask us to imagine paradise, we would probably picture a place filled with trees, flowers, waterfalls, and beaches. Hardly anyone would think of a concrete jungle.

That preference is not accidental: it has deep roots in our brains. Neuroscience shows that our connection with nature stems from a biological need, not a mere aesthetic taste. Our nervous system evolved over millions of years in natural environments, and even today, it continues to seek in them signs of safety, balance, and well-being.

The human eye is designed to process fractal patterns. When it encounters them, the body responds by reducing physiological stress.

However, most of us live in cities surrounded by asphalt, noise, and gray surfaces. This distancing from the natural environment affects not only our physical health but also our mental health.

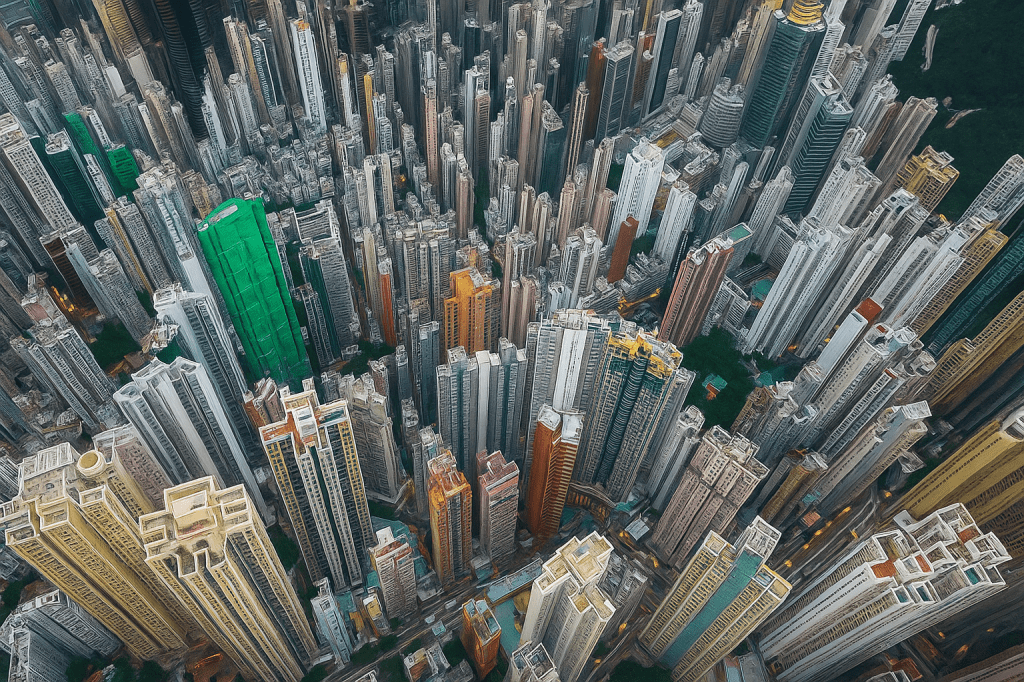

The extreme density of Hong Kong reveals the limits of urban life when natural space disappears. Among horizonless towers, the human brain loses its biological references: stress, anxiety, and cognitive fatigue rise. What optimises urban land often erodes mental wellbeing and environmental balance.

The profound impact on the brain and mood

Contact with natural environments is not only relaxing—it is actively restorative. Nature allows us to disconnect from the constant demands of daily life and immerse ourselves in tranquillity. This interaction enhances our mental well-being and strengthens our connection with the world around us, helping us recover energy and mental clarity.

1. The antidote to stress: cortisol and the heart

- Scientific evidence: Numerous studies, including those that measure physiological biomarkers, have found that interacting with plants or gardening significantly reduces levels of cortisol, the main stress hormone.

- In practice: This translates to a decrease in heart rate and blood pressure. The brain interprets natural environments (fractal patterns, green colours) as safe and low danger, which immediately activates a relaxation response.

2. Mental Recovery: The Attention Restoration Theory (ART)

- Scientific Evidence: Research in environmental psychology supports the Attention Restoration Theory (ART). Directed attention (the type we use to work or concentrate on complex tasks) becomes depleted. Nature, on the other hand, activates our involuntary attention (captivating and effortless).

- In practice: A simple view of a garden or a brief walk in a park allows our brain to recover, like recharging a mental battery. This results in an improvement in concentration, memory, and overall cognitive function.

3. Boosting the Mood: From Earth to Brain

- Scientific evidence: Gardening and contact with the soil have been linked to the release of serotonin, a key neurotransmitter for well-being. This effect has even been attributed to a natural soil bacterium, Mycobacterium vaccae, which may have antidepressant properties.

- In practice: Nature acts as a mood stabilizer, helping to mitigate mild symptoms of depression and anxiety, and fostering feelings of calm and satisfaction.

The urban landscape as a biological activator.

In dense cities, noise, lack of greenery, and visual overstimulation raise cortisol levels —the stress hormone— reminding us that architecture also shapes our hormonal responses.

Beyond Wellbeing: Environmental Benefits of Control

The integration of nature into architecture also provides essential functional benefits for creating healthier and more efficient environments:

- Improvement of indoor air quality (evidence from houseplants):

- Houseplants can help filter common indoor air pollutants (such as benzene and formaldehyde), a finding supported by studies from NASA and environmental agencies.

- Thermal and acoustic control (green walls and roofs):

- Green roofs and walls reduce the “urban heat island” effect by providing shade and cooling through evaporation. Furthermore, they act as natural acoustic insulators, creating quieter and more comfortable indoor environments.

Left: Hyde Park (London), a green oasis amid urban noise. Right: Villa Borghese (Rome), where nature and classical architecture meet in harmony.

The contemplation of nature is a form of collective meditation: the cherry blossoms and tulip fields offer a visual respite that reduces stress, enhances attention, and awakens emotions of calm and shared wonder.

Integrating Green: Biophilia-Based Recommendations

To design or redesign spaces aligned with scientific evidence, we must go beyond the decorative use of plants. Biophilic design, supported by neuroarchitectural research, transforms nature into an active health strategy.

| Neuroarchitectural Principle | Design Recommendation | Scientific Basis |

| Views of Nature | Maximise views of vegetation (parks, trees, or indoor gardens) from work, rest, and healthcare areas. | The simple sight of nature accelerates recovery and reduces stress (Ulrich, R.S.). |

| Natural Patterns | Incorporate patterns inspired by nature, such as wood textures or fractal designs (repetitive forms found in nature) in materials. | Exposure to fractal patterns reduces physiological stress by 60% (Taylor & Speckman). |

| Presence of Living Elements | Include green walls, vertical gardens, accessible inner courtyards, or a dense number of indoor plants. | The physical presence of plants improves concentration and reduces discomfort (Bringslimark et al.). |

| Access to Natural Light | Ensure that indoor and outdoor green spaces receive adequate sunlight, which has been shown to be vital for mood regulation (circadian rhythm). | Natural light has a positive influence on mood and socioemotional wellbeing. |

Final Reflection

The integration of nature into architectural design is not an aesthetic luxury but a strategic investment in health, productivity, and mental balance. Applying neuroarchitectural principles grounded in biophilia enables us to create spaces that not only shelter us, but also heal and inspire.

Spaces rich in natural light, vegetation, and sustainable materials nurture a profound bond between people and place, enhancing creativity and reducing stress. Moreover, natural elements improve air quality, thermal comfort, and encourage healthier lifestyles by inviting interaction with the environment.

Ultimately, architecture must not only serve function—it must restore the human spirit. In reconnecting design with nature, we design not just for the body, but for the brain and the soul.

References

Roger S. Ulrich, “Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments,” Journal of Environmental Psychology, 11 (1991), pp. 201–230. A key study that shows how natural environments promote stress recovery, while urban ones hinder it. sciencedirect.com+2ResearchGate+2

R. Berto, “The Role of Nature in Coping with Psycho-Physiological Stress”, Frontiers in Psychology, 5 (2014). A review that links exposure to nature with the reduction of negative mood and improvement in emotional well-being. PMC

M. Hedblom et al., “Reduction of physiological stress by urban green space in a multisite study”, Scientific Reports, 9 (2019). A study that demonstrates physiological benefits (including restored attention) of urban green spaces. Nature

Mycobacterium vaccae: Exposure to this soil bacterium has been associated with increased serotonin and positive effects on mood. For example, “Soil Bacteria Work in a Similar Way To Antidepressants,” Medical News Today (2007). Medical News Today

Recent studies: “Effects of Immunization With the Soil-Derived Bacterium M. vaccae on Stress Coping Behaviours and Cognitive Performance…” (Frontiers in Physiology, 2021) delve into the mechanism of action. PMC+1

Taylor, R. P. (2006). Reduction of physiological stress using fractal art and architecture. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 10(4), 405–419. Project Muse