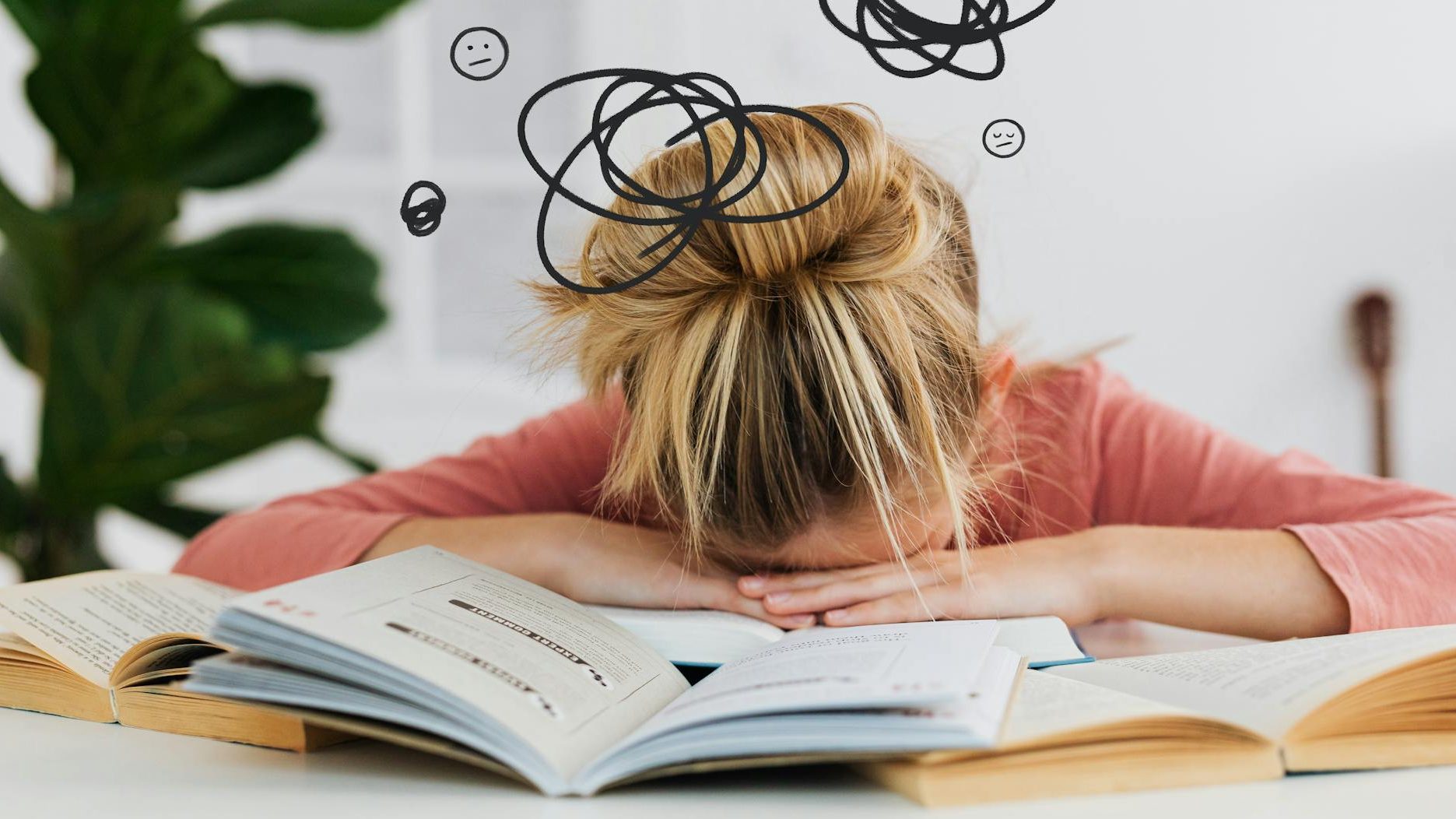

Imagine a typical work morning: you have an urgent report to finish, a list of tasks waiting, and a firm intention to stay focused and make progress. You sit down to work, but a stream of external and internal stimuli begins to interfere: a noise from the street, an intrusive thought, a sudden idea. Nothing seems to let you hold your focus or move forward as you planned.

Tension builds. You get up to fetch some water, check your phone, open an email… and by the time you reach the kitchen, you can no longer remember what you were going to do. Minutes slip by as you leaf through a magazine, trying—unsuccessfully—to pick up the thread again. The day keeps moving, the report remains untouched, and by then you’re already exhausted.

This rollercoaster of distractions is not unusual—it is the daily reality for many people living with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

Left — Chaotic visual overload: Too many competing stimuli pull attention away, making it harder to think clearly. Clutter, unfinished tasks and visual noise create a cycle of distraction and overwhelm.

Right — Visual clarity and sensory calm: An organised space with warm textures and essential items only reduces cognitive load. Natural light, soft materials and functional order create an environment that supports focus and well-being.

What is ADHD?

Put simply, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurobiological condition that affects the brain’s executive functions, such as:

- sustained attention

- emotional regulation

- planning and working memory

- sensory processing

- impulse control

It is not a matter of “trying harder” to concentrate, but of how the brain manages information. In ADHD, the filtering of stimuli is less efficient and the alert network remains more active, meaning that even small details in the environment can become distracting. In addition, differences in dopamine regulation make it harder to start tasks, maintain habits and keep spaces organised.

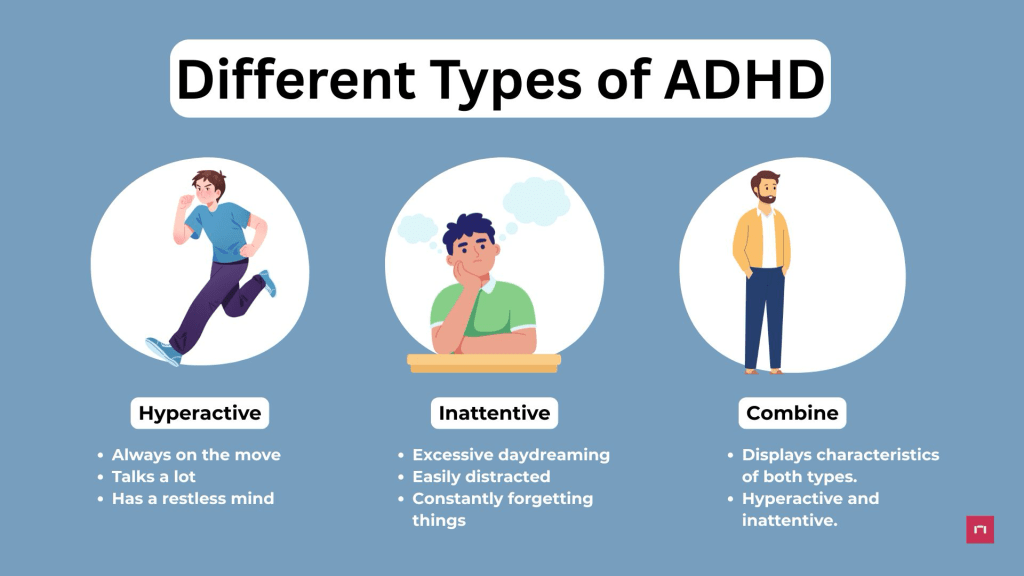

How It Manifests in Children and Adults

Although the core features of ADHD remain the same, its expression changes with age:

In children:

Physical hyperactivity, impulsivity and difficulty staying still or following instructions are more prominent. Disorganisation often appears in schoolwork, backpacks and bedrooms.

In adults:

Hyperactivity becomes internal — mental restlessness, racing thoughts. Executive difficulties show up in everyday responsibilities: bills, deadlines, emails, appointments, household tasks. The disorganisation is more subtle, but just as limiting.

Many people reach adulthood without a diagnosis, navigating a life that never quite seems to fit the way their mind works.

Many live for years with unrecognised ADHD, not fully understanding why their brain works differently or having undergone an assessment that explains it.

Key Statistical Data

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), ADHD is considered persistent when symptoms continue to cause significant impairment in key areas of life —such as academic performance, interpersonal relationships or work— even after environmental adjustments have been made at school, at home or in other relevant settings.

Globally, the most consistent estimates place the prevalence of ADHD at around 8% of children and adolescents, with studies ranging between 5% and 7.6% depending on age group and diagnostic criteria.

In England, recent data from NHS Digital —based on prevalence rates established by NICE— indicate that approximately 2.5 million people may have ADHD, including those who have not received a formal diagnosis. This corresponds to 3–4% of the adult population and around 5% of children and young people, of whom 621,000 are estimated to be under 17. These figures should be interpreted with caution, as they are derived from population-level estimates.

Everyday challenges of ADHD: when daily life becomes a sensory and executive maze

People with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) face constant challenges that have nothing to do with a lack of effort. They arise because the brain processes attention, organisation and emotional regulation differently, making seemingly simple activities feel like an uphill climb.

1. In education

At school, the mind can easily lose the thread:

- listening to instructions,

- focusing on long tasks,

- keeping to schedules or handing in work on time.

All of this, combined with years of corrections and comparisons, can affect self-esteem and academic confidence.

2. In the workplace

In adult life, executive functions play a central role. ADHD can make it difficult to:

- start projects,

- prioritise tasks,

- meet deadlines,

- maintain an organised workspace.

Impulsivity or accumulated frustration can also create tension in meetings and professional relationships.

3. In personal relationships

ADHD impacts close connections as well.

Distraction can appear as disinterest, impulsive speech can lead to misunderstandings, and household disorganisation can create friction with those who share the space. These are not character flaws—they are the effects of a brain that manages information differently.la información de forma diferente.

It is estimated that around 50% of children with ADHD continue to experience significant symptoms in adulthood, highlighting the importance of early identification, ongoing support and environments that respond to their needs.

Why a diagnosis — and the right strategies — make all the difference

Naming what is happening brings clarity and relief. A diagnosis does not “label”; it explains. It helps us understand that these difficulties have a neurobiological basis and opens the door to real solutions.

Recognising ADHD:

- reduces self-blame and chronic stress,

- improves self-esteem by offering a coherent explanation,

- facilitates access to effective treatments and psychoeducation,

- prevents associated difficulties such as anxiety, depression or poor performance,

- allows for practical adjustments at school, work and home that ease the daily load.

Understanding ADHD transforms the relationship one has with oneself and with the environment. And it is precisely here that neuroarchitecture plays a quiet but powerful role: creating spaces that support, regulate and make daily life more manageable.

ADHD and Neuroarchitecture: Strategies to Reduce Mental Overload

The built environment can intensify the challenges of ADHD when it is filled with competing stimuli—noise, clutter, harsh lighting—that saturate attention and disrupt both concentration and emotional regulation. A chaotic space distracts the mind and makes even simple tasks feel overwhelming.

For people with ADHD, an intuitive and supportive interior design can be the difference between a scattered day and one that feels coherent and manageable. Below are six neuroarchitectural strategies that help create spaces of calm and focus, tailoring the environment to the way the ADHD brain processes information.

1. Reduce Visual Load (Balancing Order and Stimulation)

The ADHD brain is particularly sensitive to visual clutter. The aim is not stark minimalism, but functional visual clarity.

Clear Key Surfaces:

Keeping desks and kitchen counters free of excess items reduces the number of stimuli competing for your attention.

Thoughtful Storage:

Opaque boxes, baskets and labelled containers help hide clutter while maintaining easy access.

Visible Task Board:

A central task board or whiteboard offloads working memory and supports planning.

Fewer objects in sight mean fewer demands on attention.

2. Manage Sound Strategically

Sudden or inconsistent noise can be a major barrier to concentration. Neuroarchitecture seeks to soften and regulate the acoustic landscape.

Textile Absorption:

Thick curtains and rugs help dampen noise and reduce echo.

Sealed Openings:

Door and window seals limit intrusive outdoor sounds.

Auditory Anchors:

White noise or natural soundscapes—rain, waves, wind—can mask distractions and enhance focus.

3. Use Lighting Intentionally

Light shapes circadian rhythms and levels of alertness.

Warm Light (2700–3000K):

Soft, warm lighting promotes calm in relaxation areas.

Indirect Illumination:

Floor and side lamps are gentler than overhead lights, which can feel harsh or overstimulating.

Reduce Glare:

Position workstations to minimise reflections and visual fatigue.

4. Create Clearly Defined Zones

The ADHD mind benefits from environments where each area signals a clear purpose. Zoning reduces the sense of “everything happening at once” and helps prevent decision paralysis.

Work Zone:

A desk used exclusively for work.

Rest Zone:

A dedicated space for unwinding, free of work-related cues.

Landing Station:

A fixed spot near the entrance for keys, wallet and documents.

Creative Zone:

A space where creative mess is permitted—but contained.

5. Choose Calming Textures

Textures can soothe or overstimulate. Natural, soft materials help regulate the sensory system.

Soft Layers:

Blankets, cushions and upholstered furniture bring tactile comfort.

Natural Finishes:

Wood, cotton, linen and wool are visually quieter than shiny plastics or cold metals.

6. Support Routines with Spatial and Olfactory Cues

The environment can act as an external memory system—essential for ADHD.

Physical Cues:

- A visible inbox tray for mail and pending items.

- A dedicated container for objects that tend to go missing.

- A chair or hook for everyday clothing (reducing the familiar “chair-floor”).

Olfactory Anchors:

Scents can mark transitions effectively:

- Citrus or mint to initiate tasks and energise focus.

- Lavender or chamomile to signal winding down and prepare for rest.

Spaces with few visual distractions, simple lines and natural materials help reduce cognitive overload. By removing excess and highlighting what is essential, these environments support concentration, emotional regulation and a clearer state of mind.mental.

ADHD is not a matter of lacking effort, but of processing the world differently. This is why the built environment can either intensify challenges or ease much of the daily burden. Applying neuroarchitectural strategies—visual organisation, sensory regulation and intentionally designed spaces—doesn’t “cure” ADHD, but it does create conditions that support focus, emotional balance and a calmer everyday life. A well-designed space may not heal, but it does accompany. It becomes a steady source of support in a life that already demands more energy than most people realise.

Further reading

What is ADHD https://adhduk.co.uk/about-adhd/

ADHD in children and young people https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/adhd-children-teenagers/

ADHD in adults. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/adhd-adults/

17 Books to Help you Understand ADHD in Adulthood: Essential Reads for Support and Empowerment. https://www.lovereading.co.uk/blog/books-to-help-you-understand-adhd-in-adulthood-essential-reads-for-support-and-empowerment-9193