Over the past decade, tiny houses have shifted from an alternative curiosity to an aspirational symbol. Small, tidy, and carefully photographed, they appear to promise a simpler way of living. But when we move beyond the image and consider the body that inhabits these spaces—the brain, the senses, everyday life—the question changes:

Can a dwelling of minimal dimensions sustain physical and mental balance over the long term?

What is a tiny house?

A tiny house is a dwelling of very small dimensions, typically between 15 and 40 square metres, designed to concentrate the essentials of living into the minimum possible space. While its philosophy aims to reduce environmental impact and financial burden, from a neuroarchitectural perspective this reduction does not always translate into greater wellbeing.

When multiple functions—sleeping, working, cooking, resting—are layered into the same space without clear transitions, the brain is required to process too many stimuli within a confined area. This increases cognitive and sensory load. Such conditions can be demanding for anyone, but they are often particularly challenging for neurodivergent individuals, whose sensory systems tend to be more sensitive to stimulus accumulation and to the lack of spatial separation.

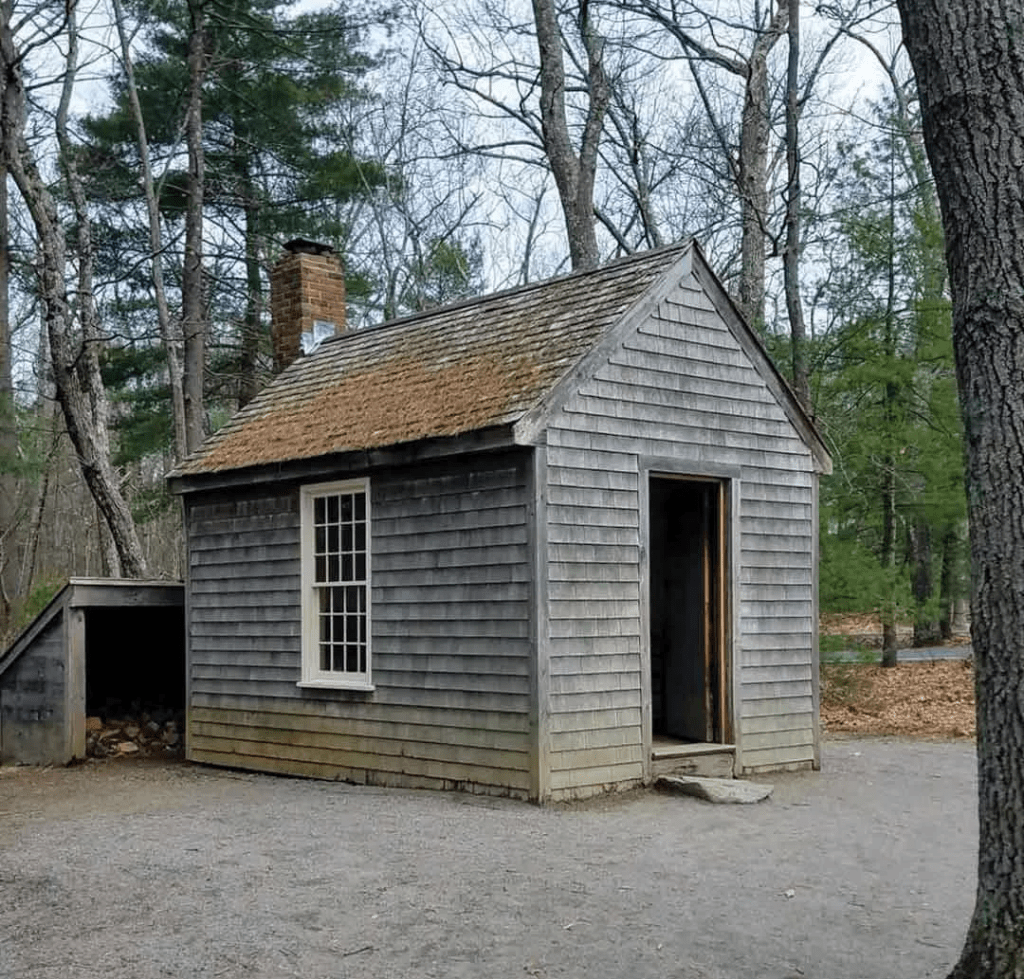

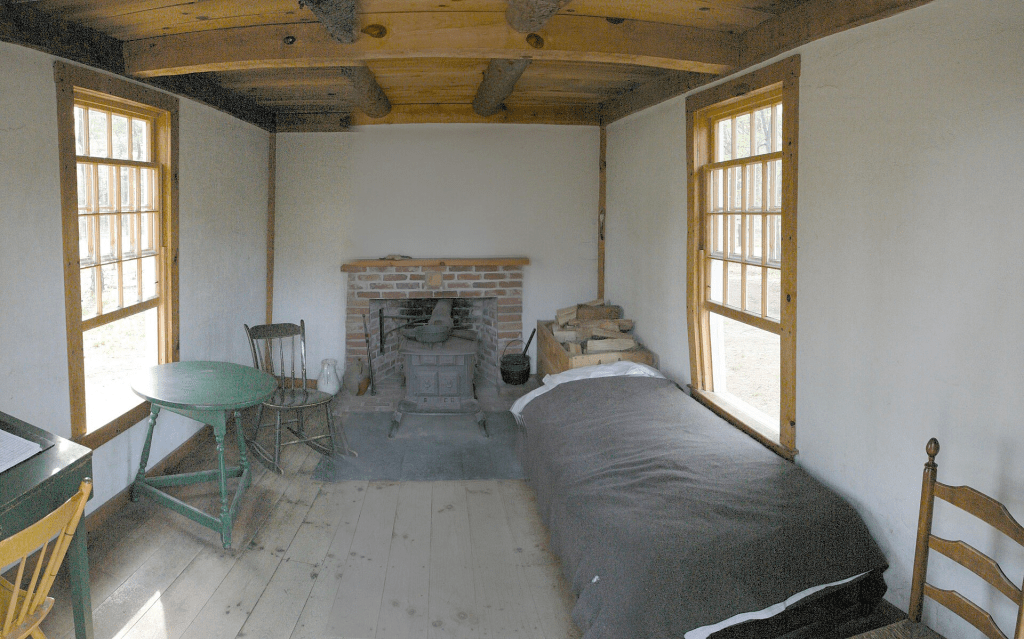

Two views of the same spatial experiment. From the outside, a minimal architecture in direct dialogue with the landscape; from within, a compact yet legible interior, where light, proportion, and connection to the surroundings expand the experience of inhabiting the space. More than a precursor to the tiny house, Walden offers a lesson that remains relevant today: wellbeing depends not on size, but on how space mediates between body, mind and nature.

Origins: an old idea with a new name

Living in minimal spaces is not a contemporary invention. In the nineteenth century, Henry David Thoreau built his cabin at Walden as an experiment in self-sufficiency and personal reflection. It was not about deprivation, but about conscious choice.

From Thoreau’s cabin to the responses that emerged after the 2008 financial crisis, minimal housing has remained a recurring theme. Yet in 2026, after years of consolidated hybrid working and amid a global affordability crisis, the tiny house is no longer merely an experiment. It has become a structural response to an increasingly strained housing market.

Why are tiny houses on the rise today?

Their current popularity stems from a convergence of pressures: rising housing costs worldwide, labour precarity, constant mobility, growing distrust in models of unlimited growth, and a form of psychological fatigue linked to consumption and accumulation—further amplified by the idealisation of minimalism as a lifestyle.

What spatial conditions does the brain need to feel safe and comfortable?

Much of today’s demand reflects this fatigue and the appeal of simplification. But one critical factor often goes unexamined: social-media aesthetics. Images convey order and control, yet the brain does not inhabit photographs—it inhabits volumes, sequences, and sensory conditions over time. What the image leaves out is the prolonged, lived sensory experience of space.

Mobility and close contact with nature can enhance feelings of freedom and autonomy, but they also introduce a key tension: a format designed for temporary use that is increasingly adopted as an everyday dwelling, with clear limits in terms of spatial expansion, privacy, and sensory regulation.

Real advantages

Tiny houses can work—and work very well—in highly specific circumstances: when they are designed for one or two people at most; when they are used as temporary or transitional dwellings; or when they function as a retreat, studio, or place of withdrawal. Their habitability improves significantly when there is a direct relationship with the outdoors and when the design prioritises height, natural light, and spatial flexibility, allowing a small space to feel more open, legible, and breathable.

Among their most tangible benefits are:

A sense of control.

A small space allows for rapid appropriation of the environment, reducing cognitive load when order is functional and intentional.

Biophilic connection.

When there is a direct link to the exterior, the brain does not register the wall as a hard boundary but the horizon beyond it, mitigating the sensation of enclosure.

Voluntary simplicity.

When chosen consciously, simplicity can activate reward pathways, transforming scarcity into containment rather than deprivation.

Spatial clarity and a strong connection to the outdoors expand the perceived sense of space, yet the constant overlap of functions and sustained sensory stimulation can become demanding over time—particularly for individuals with heightened sensory sensitivity.

The limits of the model: the sensory challenge

From a neuroscientific perspective, the primary limitation of tiny houses is not size per se, but the management of peripersonal space—the immediate area surrounding the body that the brain processes as an extension of the self. When this space is constantly encroached upon, the experience of inhabiting can become cognitively and emotionally demanding.

Three factors concentrate the model’s main challenges:

Crowding and allostatic load (accumulated physiological stress).

The absence of clear gradients between public and private zones prevents the brain from entering recovery states. The constant overlap of functions—sleeping, working, cooking—keeps the nervous system in sustained alert.

Sensory saturation.

In extremely compact spaces, sounds, smells, and visual stimuli have little opportunity to dissipate. Without even minimal sensory zoning, the nervous system becomes progressively exhausted.

The normalisation of precarity.

When tiny houses are presented as a structural response to the housing crisis, there is a risk of legitimising insufficient standards of habitability under the label of “simple living”, disproportionately affecting those with the least freedom of choice.

Together, these conditions can translate into sensory overload, sustained stress, and mental fatigue, intensifying conflicts in shared living situations and increasing emotional vulnerability over the long term.

A tiny house works best when it is a conscious choice, not a forced imposition.

A minimal space that expands perceptually through natural light, timber, and direct contact with the landscape. Here, wellbeing does not stem from size, but from sensory control, spatial clarity, and the ability to “step outside without leaving”—living small without feeling enclosed.n sentirse encerrado.

Between opportunity and risk: a critical reading

A tiny house works best when it is situated within an open and generous setting, where outdoor space can be integrated as a genuine extension of the interior. The presence of a porch, terrace, or intermediate outdoor area is not an optional amenity but a meaningful neurophysiological regulator: it expands the perceived living space, supports biophilic affiliation, and helps reduce stress by enabling ongoing contact with natural light, fresh air, and environmental rhythms.

Equally important is the way design supports circadian rhythms. The admission of natural light, its progression throughout the day, and the vertical dimension of the space all shape how the brain evaluates an environment. A compact volume that is tall, well ventilated, and properly oriented is typically perceived as breathable and safe; by contrast, a low, dark, or poorly lit space can intensify physiological arousal and feelings of claustrophobia, even when it is aesthetically refined.

Finally, spatial legibility plays a crucial role. In minimal dwellings, clear zoning helps reduce cognitive load and allows the brain to distinguish between states of activity and rest. This does not require additional walls, but rather perceptible transitions achieved through light, height, materiality, or proximity to the exterior. When these strategies are consciously integrated, a tiny house can mitigate many of its inherent limitations and become a more regulating and sustainable living environment over time.

A model that promises energy independence and low environmental impact, yet continues to raise critical questions about habitability, wellbeing, and long-term living in minimal spaces.

Conclusion: it’s not the size, it’s the relationship with space

Tiny houses are not a universal solution, but neither are they inherently flawed. Like any housing typology, they succeed—or fail—depending on context, degree of choice, and the way space engages with those who inhabit it.

From this model emerges a key lesson: we may not need as much space as we think, but we do need design that is more attuned to how the body and brain actually function. Wellbeing depends less on square metres than on spatial quality—on a meaningful relationship with the outdoors, clear transitions between uses, sensory regulation, and layouts that respond to daily rhythms.

For some people, this form of dwelling represents freedom: mobility, direct contact with nature, reduced financial burden, and a lighter relationship with living itself. In such cases, a tiny house can become a consciously chosen refuge rather than a forced compromise.

In 2026, the real challenge for architecture is not how much space we can strip away, but how much mental health we are able to embed within the spaces we inhabit.

Suggested Readings

University of Kent Sustainability at Kent

All buildings great and small: the spectacular rise of tiny homes https://www.ube.ac.uk/whats-happening/articles/tiny-homes/

Why the tiny house is perfect for now https://www.bbc.co.uk/culture/article/20211215-why-the-tiny-house-movement-is-big