How three disciplines converge to reshape how we live, feel, and design.

A Curious Beginning

Why do some spaces calm us while others make us feel uneasy?

Why does a walk through a forest restore our energy, while a noisy corridor drains it?

For decades, designers and researchers have asked these questions from different angles. In recent years, three fields—neuroarchitecture, environmental psychology, and biophilic design—have emerged as powerful lenses to understand how space shapes the human experience. Their origins are different, their methods distinct, but their conclusions often align. And when we bring them together, something even more meaningful happens.

What they are

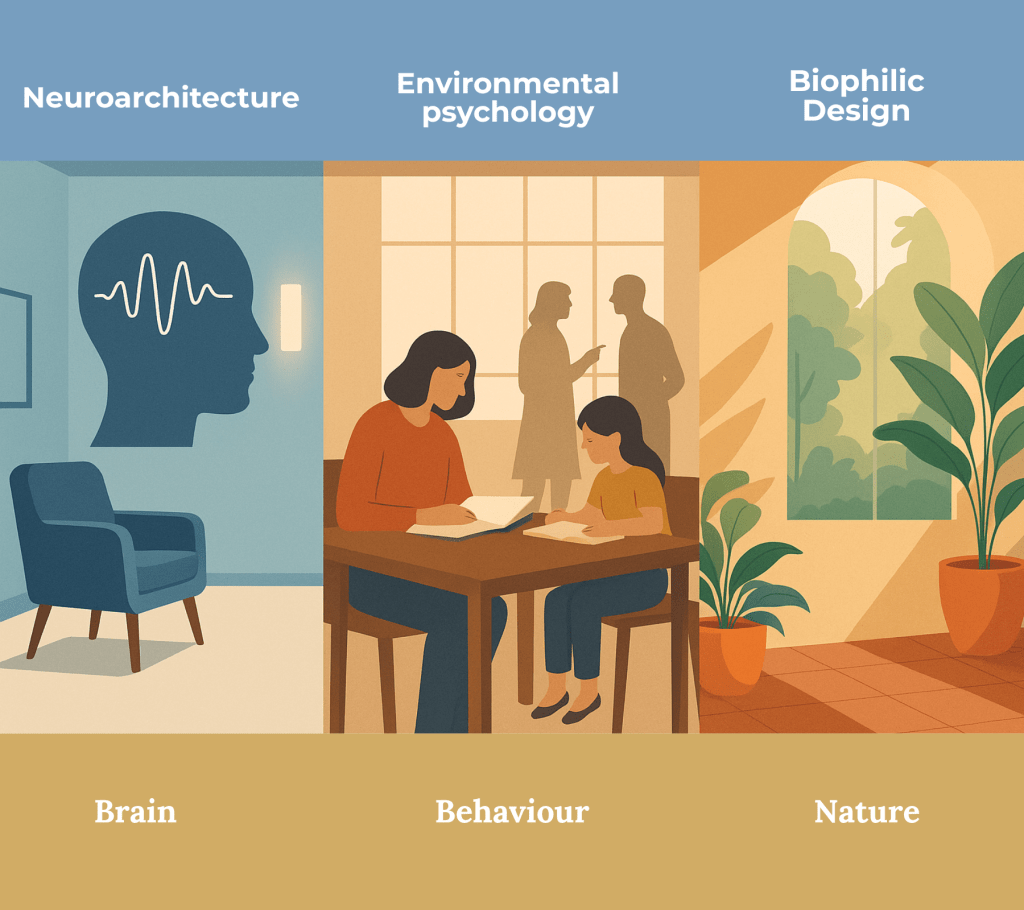

- Neuroarchitecture is the intersection between neuroscience and architecture. It explores how the brain and body respond to spatial qualities such as light, scale, acoustics, and orientation. Grounded in biology, it seeks measurable correlations between design and neurological states—like stress, memory, focus, or spatial anxiety.

- Environmental Psychology looks at the reciprocal relationship between people and their environments. It is less concerned with aesthetics and more with behaviour—how surroundings influence attention, emotion, social interaction, or even ethical decisions. It draws from sociology, psychology, geography, and design studies.

- Biophilic Design is a creative philosophy rooted in our evolutionary connection with nature. It assumes that humans thrive when they are surrounded by elements that mirror natural systems—such as daylight, greenery, water, and organic patterns. It builds on the “biophilia hypothesis” which proposes that humans have an innate need to affiliate with nature.

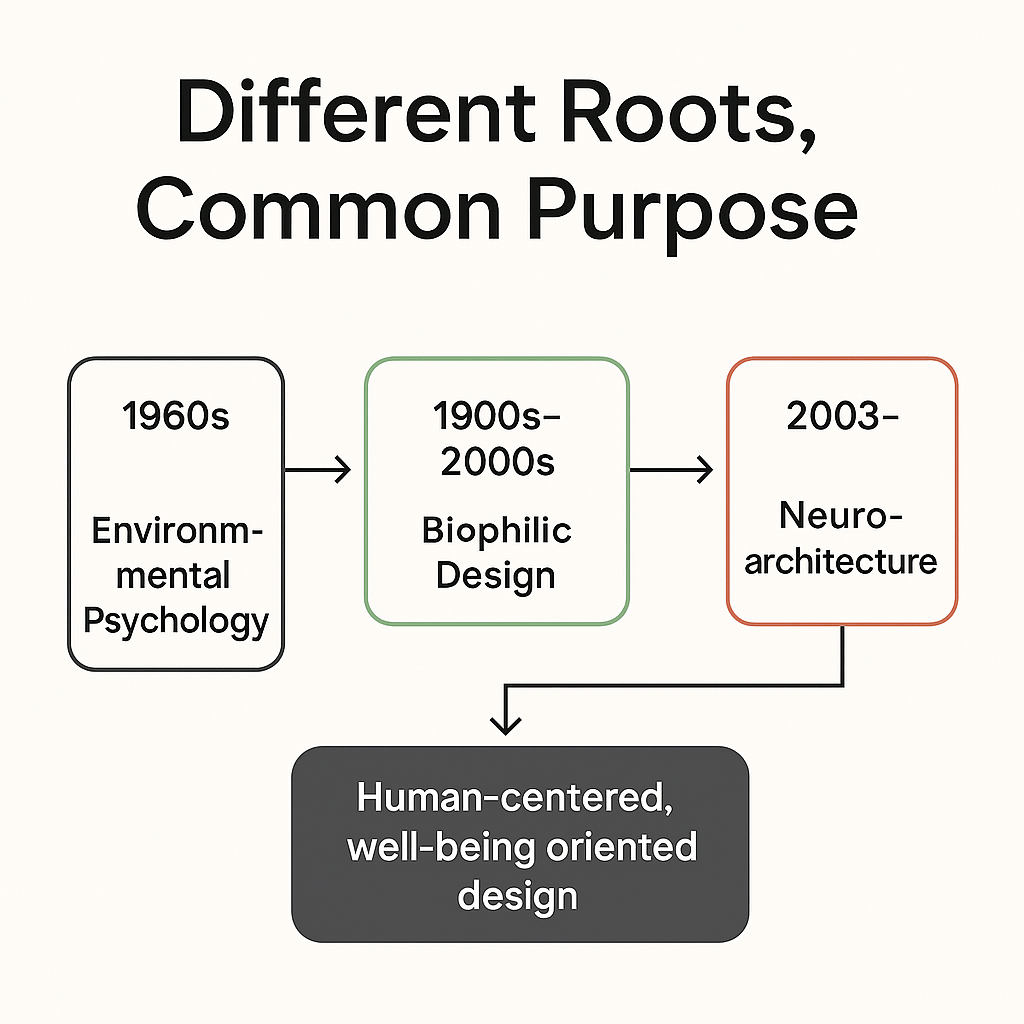

Where They Come From

- Neuroarchitecture arose from advances in neuroscience and cognitive science in the early 2000s. It grew as architects sought to design buildings based not only on function or form, but on how the brain perceives and inhabits space.

- Environmental Psychology emerged in the 1960s and 70s, during the height of urbanisation, pollution, and mass housing. It developed in response to a growing concern for how the built environment affects human health, behaviour, and quality of life.

- Biophilic Design became more prominent in the late 20th and early 21st centuries as part of the sustainability movement. It builds on ecological thinking, health sciences, and design frameworks such as the 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design (Terrapin Bright Green).

How they work

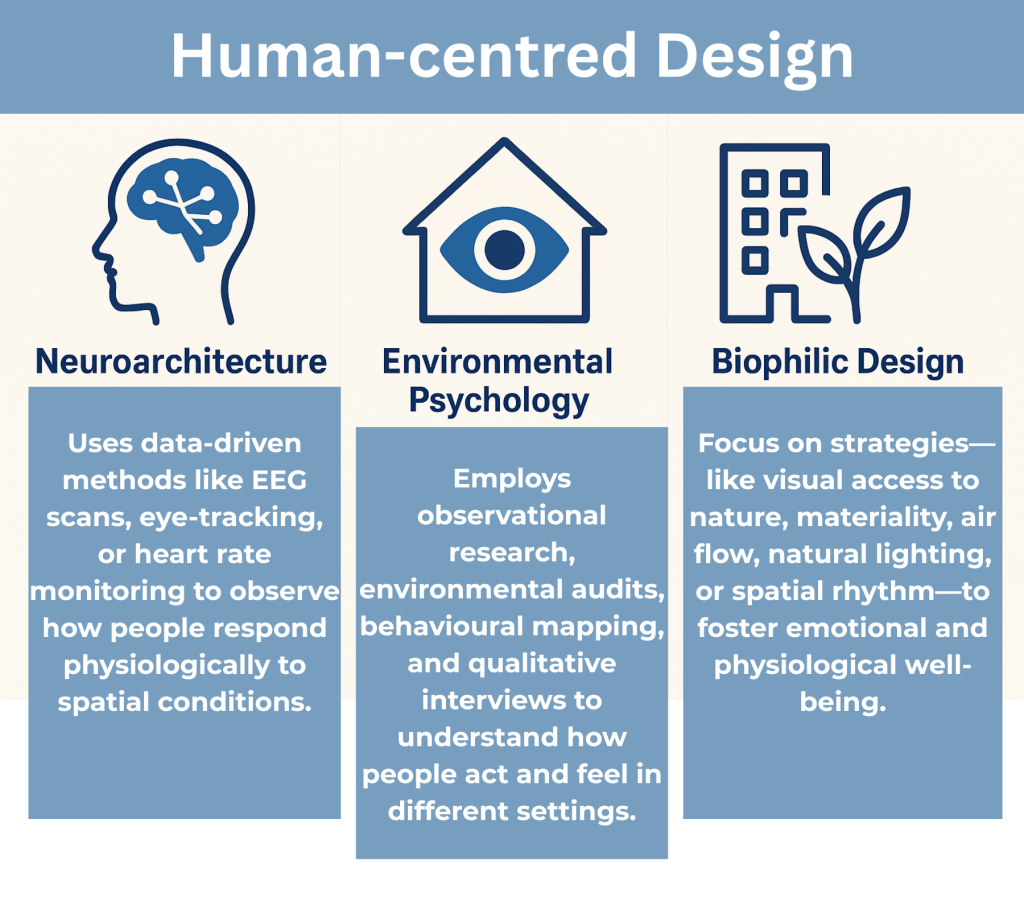

Each of these fields offers different tools:

- Neuroarchitecture uses data-driven methods like EEG scans, eye-tracking, or heart rate monitoring to observe how people respond physiologically to spatial conditions.

- Environmental Psychology often employs observational research, environmental audits, behavioural mapping, and qualitative interviews to understand how people act and feel in different settings.

- Biophilic Design is applied through architectural and interior strategies—like visual access to nature, materiality, air flow, natural lighting, or spatial rhythm—to foster emotional and physiological well-being.

Shared Goals, Different Paths

Despite their differences, all three disciplines share a common aim: to design environments that support human health, cognition, and connection.

Yet, they do so in complementary ways:

Neuroarchitecture focuses on the brain. Environmental psychology focuses on behaviour. Biophilic design focuses on emotion and nature.

They speak in different languages—scientific, social, ecological—but all are responding to the same call: that space matters. Not abstractly, but personally, physiologically, even spiritually.

Why This Matters Now

We live in a time of sensory overload, climate anxiety, and urban fatigue. Many of our cities, schools, hospitals, and homes were not built with neurodiversity, mental health, or ecological balance in mind.

That’s why these disciplines are more urgent than ever.

They remind us that design is not neutral. Every wall, corridor, material or window is influencing how we feel—whether we notice it or not.

When we integrate their insights, we don’t just build better spaces.

We create places that support rest, learning, belonging, and joy.

A Converging Conclusion

Though neuroarchitecture, environmental psychology, and biophilic design have emerged from different worlds, they’ve come to remarkably similar conclusions:

Our environments are not passive backgrounds. They are active participants in our wellbeing.

References

Coburn, A., Vartanian, O., & Chatterjee, A. (2017). Buildings, beauty, and the brain: A neuroscience of architectural experience. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 29(9), 1521–1531. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01146

Eberhard, J. P. (2009). Brain Landscape: The Coexistence of Neuroscience and Architecture. Oxford University Press.

Evans, G. W. (2003). The built environment and mental health. Journal of Urban Health, 80(4), 536–555. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jtg063

Gifford, R. (2014). Environmental psychology matters. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 541–579. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115048

Kellert, S. R., Heerwagen, J. H., & Mador, M. L. (Eds.). (2008). Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Wiley.

Terrapin Bright Green. (2014). 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design: Improving Health and Well-Being in the Built Environment. https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/reports/14-patterns/

One thought on “Integrating Neuroarchitecture, Psychology, and Biophilic Design”