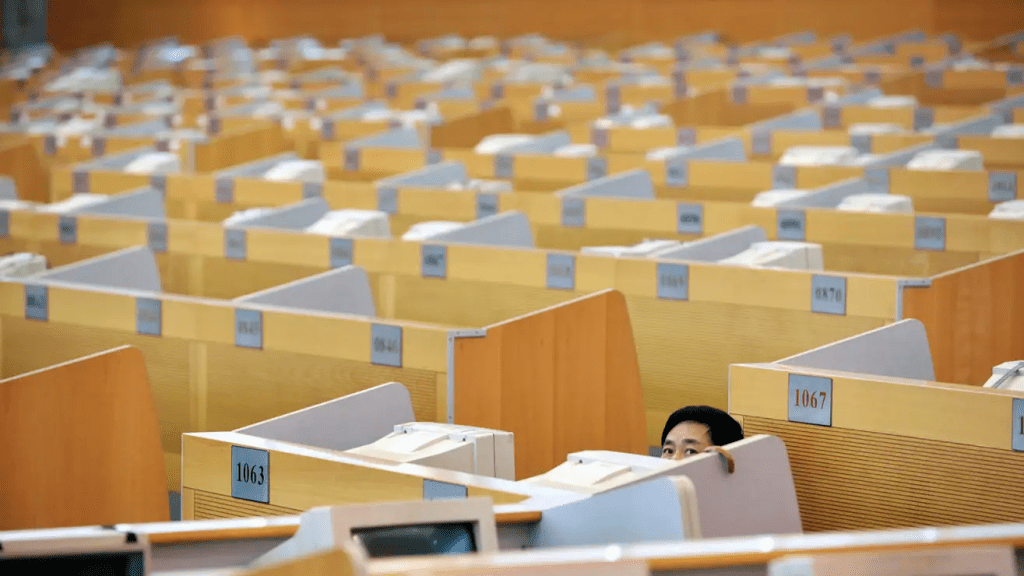

Imagine you’re a young creative professional starting your first job. You’re full of ideas, eager to collaborate, ready to grow. But the moment you step into the office, you feel it—a grid of identical cubicles, harsh lighting overhead, no windows, no space to breathe.

The atmosphere is oddly quiet, yet not private. Conversations are muffled but audible. Your colleagues glance up, but no one makes eye contact. There’s little sense of community, yet no sense of solitude either. It’s as though you’re both too visible and completely unseen.

You can’t work comfortably, nor can you strike up conversations that feel genuine. Collaboration feels forced, and deep focus impossible. As the hours pass, you begin to wonder—not just how you’ll finish your tasks, but whether you can really see yourself staying in this place for long.

Environment and the Brain

Our surroundings significantly influence our inner world and mental state, impacting emotions, thoughts, and behaviours. Neuroscience supports the idea that environments —whether at home, work, or school—can enhance or diminish feelings of comfort, focus, and productivity.

Neuroscience confirms what many designers have long sensed: the environment around us affects our brain chemistry—which in turn shapes our emotions, thoughts, and behaviours.

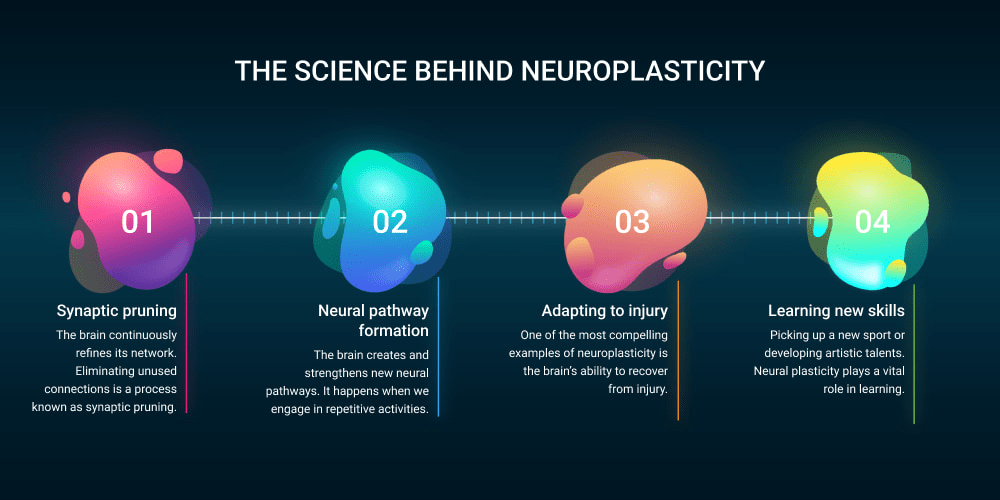

One of the key mechanisms behind this is neuroplasticity, the brain’s remarkable ability to reorganise itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. When we spend time in calming, stimulating, or disorienting environments, our brains adapt accordingly.

Spaces that support learning, restoration, or creativity do so not accidentally, but by actively shaping our neural pathways over time, which in turn shapes our emotions, thoughts, and behaviours.

“Every man can, if he so desires, become the sculptor of his brain.”

Santiago Ramón y Cajal

The Science of Neuroplasticity

More than a century ago, Nobel laureate Santiago Ramón y Cajal laid the foundations of modern neuroscience with his Neuron Doctrine—but he also planted the seeds of an idea that remains central to neuroarchitecture today: the brain is malleable.

In his observations, Ramón y Cajal recognised that the nervous system could adapt and reconfigure itself in response to experience. This concept, now widely validated by contemporary research, reinforces the truth that we can shape our brains—and that our environments are active participants in that process.

An office space design to promote creativity and collaboration, featuring wooden furniture and natural light.

Jonas Salk: A Vision for Creative Space

Before developing the first safe and effective polio vaccine, Dr. Jonas Salk felt immense pressure and creative block. Retreating to Assisi, Italy, he discovered that the serenity and beauty of the monastic environment sparked some of his most profound insights.

This experience inspired him to create a research facility that would do the same for others—spaces that would foster scientific rigour and spiritual reflection. Salk believed that well-designed architecture could actively enhance creativity, productivity, and collaboration.

In 1957, he invited architect Louis Kahn to bring this vision to life. The result was the Salk Institute for Biological Studies: a masterpiece of minimalist design and symmetrical harmony, overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Its central courtyard serves not only as a gathering space, but as a contemplative void—clearing mental space for ideas to emerge.

Salk’s philosophy positioned architecture not merely as shelter but as a catalyst for human flourishing. He envisioned the Salk Institute as both a hub for scientific discovery and a space where the environment would nurture intellectual breakthroughs. Beyond advancing research, he hoped the building itself would spark inquiry into how our surroundings affect the mind.

Architectural design, then, can change our brains and behaviour.

Fred Rusty Gage

What Is Neuroarchitecture?

Neuroarchitecture is an emerging interdisciplinary field that explores how the built environment affects our brain and behaviour. It combines insights from neuroscience, psychology, and architecture to understand how elements like light, space, colour, acoustics, and layout influence our emotions, cognition, and wellbeing. The goal is to design spaces that support mental health, focus, creativity, and human connection—spaces that not only look good, but feel right.

The Rise of Neuroarchitecture

In 2002, Salk’s vision took a formal step forward with the founding of the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture (ANFA) on the very grounds of the Salk Institute.

In his 2003 keynote for the American Institute of Architects (AIA), neuroscientist Fred “Rusty” Gage, then president of the Salk Institute, outlined the core principles of neuroarchitecture:

- The brain controls behaviour.

- Genes shape the structure and design of the brain.

- The environment influences gene expression and, ultimately, brain structure.

- Environmental change changes the brain.

- Therefore, a change in the environment changes behaviour.

- Architectural design, then, can change our brain and behaviour.

Architectural design, then, becomes a tool not just for spatial planning, but for behavioural and neurological transformation.

A Legacy of Healing Spaces

The link between the environment and mental health isn’t entirely new. Finnish architect Alvar Aalto (1898–1976) believed architecture should provide a sensitive structure aligned with nature and biology.

Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium (1929–1933) in Finland exemplified this belief. Built to treat tuberculosis patients, it maximised access to sunlight, fresh air, and nature. Rooms had large windows; balconies invited patients to rest outdoors. Interior elements—from lighting to acoustics to materials—were designed with psychological and sensory wellbeing in mind.

Situated amidst a serene pine forest in southwestern Finland, the sanatorium’s layout was meticulously planned to maximise exposure to sunlight and fresh air—key elements in tuberculosis treatment at the time. Patient rooms featured large windows, and each floor included sun balconies where patients could rest and recuperate.

In 1984, Roger S. Ulrich provided scientific backing for this approach. In his study “View Through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery”, he demonstrated that patients with views of nature recovered faster and required less medication than those facing a brick wall. His work became a cornerstone in evidence-based hospital design.

One of the most compelling contemporary examples of healing-oriented design is Maggie’s Centres in the UK. Founded by Maggie Keswick Jencks and designed by leading architects including Zaha Hadid, Norman Foster, and Thomas Heatherwick, these centres offer non-clinical environments for cancer patients and their families.

Every Centre is original and surprising, yet they all feel like part of the same family. They are calm, friendly and welcoming places, full of light and warmth. At the heart of each is a kitchen table, surrounded by thoughtful spaces that offer glimpses of nature and allow for both privacy and community.

Each space is intentionally crafted to reduce stress and promote dignity, with an emphasis on natural light, calming materials, gardens, and communal areas that encourage social connection. The design reflects a core belief: that architecture can contribute meaningfully to emotional resilience and quality of life during treatment.

What’s Next for Neuroarchitecture?

The field continues to evolve as researchers deepen our understanding of how built environments influence brain function. From how layout impacts social interaction, to how lighting and colour affect attention and mood, neuroscience now offers designers concrete insights to support better outcomes.

What once relied on intuition is now bolstered by data. Architects and neuroscientists—though guided by different methods—share a focus on creating environments that support cognitive performance, emotional regulation, and mental health.

That’s why architecture must go beyond function and form. It must consider how space feels, how it moves us, and how it supports—or undermines—our wellbeing.

Designing with the brain in mind means crafting environments that not only function well, but also feel right—spaces that nurture clarity, empathy, and human potential.

As we uncover more about how architecture influences our psychological states, the opportunity grows to shape spaces that heal, empower, and connect.

One building. One room. One detail at a time.

References

Cajal, the neuronal theory and the idea of brain plasticity. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10910026/

Workplace Woes: The ‘Open’ Office Is a Hotbed of Stress. https://ideas.time.com/2012/08/15/why-the-open-office-is-a-hotbed-of-stress/

New Research: Workers Hate Their Cubicles https://www.forbes.com/sites/susanadams/2013/11/25/new-research-workers-hate-their-cubicles/

History of Salk https://www.salk.edu/about/history-of-salk/

Revisit: ‘Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium continues to radiate a profound sense of human empathy’ https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/revisit-aaltos-paimio-sanatorium-continues-to-radiate-a-profound-sense-of-human-empathy

Ramón y Cajal, S. (1894). Neuron Theory or Reticular Theory? Translated and republished in Shepherd, G. M. (1991). Foundations of the Neuron Doctrine. Oxford University Press.

Ulrich, R. S. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224(4647), 420–421. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6143402

Salk Institute for Biological Studies. (n.d.). History and architecture. Retrieved from https://www.salk.edu/about/history/

One thought on “Neuroarchitecture: How Space Affects Your Mind”