For many people, searching for a home for the first time is an emotional shock. It is not just a financial decision: it is an unexpected test of what “home” means today.

At some point in the process, almost all of us have lived through the same scene. We step into a new flat, follow the estate agent down a narrow corridor, and suddenly find ourselves in the “living–dining area”. On the floor plan it seemed reasonable. In reality, it is barely a rectangle that fits a small sofa and, if we are lucky, a table for two. The bedroom fares no better: a double bed might fit… if we give up the wardrobe.

What surprises us most is not only the scale, but the price. The square metres shrink; the cost soars. And then the inevitable comparison arises:

How is it possible that our parents lived in homes three times larger, on proportionally lower incomes?

Between the home we imagine and the one we can afford, there is often a quiet gap that reshapes how we experience and inhabit space.

Why are new homes getting smaller?

The reduction of domestic space is no accident. It is the result of a combination of urban, economic, and social transformations that have progressively compressed everyday life.

Rising land prices

In cities such as London, Bogotá, New York, or Madrid, urban land has become steadily more expensive. To keep projects financially viable, developers reduce the size of individual units: fewer square metres per home, higher density, and higher prices.

Urban densification without spatial quality

Many cities are encouraging inward growth to improve transport efficiency and access to services. However, when densification is not accompanied by green areas, shared spaces, or social infrastructure, the result is smaller homes without the spatial support needed for balanced daily life.

Changes in household structure

The rise of single-person households and couples without children has driven the construction of compact units. The problem arises when this trend is used to justify extreme reductions in space, even though emotional, cognitive, and physical needs remain complex.

The rise of the micro-apartment

What began as a specific response in highly dense cities such as Tokyo or Hong Kong has become a global trend: studios of 15 to 28 square metres marketed as solutions to the housing crisis, often without considering their long-term effects on mental health.

Market optimisation, not wellbeing

The real estate logic prioritises return per square metre. Housing is designed to maximise profit, not to support bodies, emotions, and relationships. Spatial efficiency replaces wellbeing.

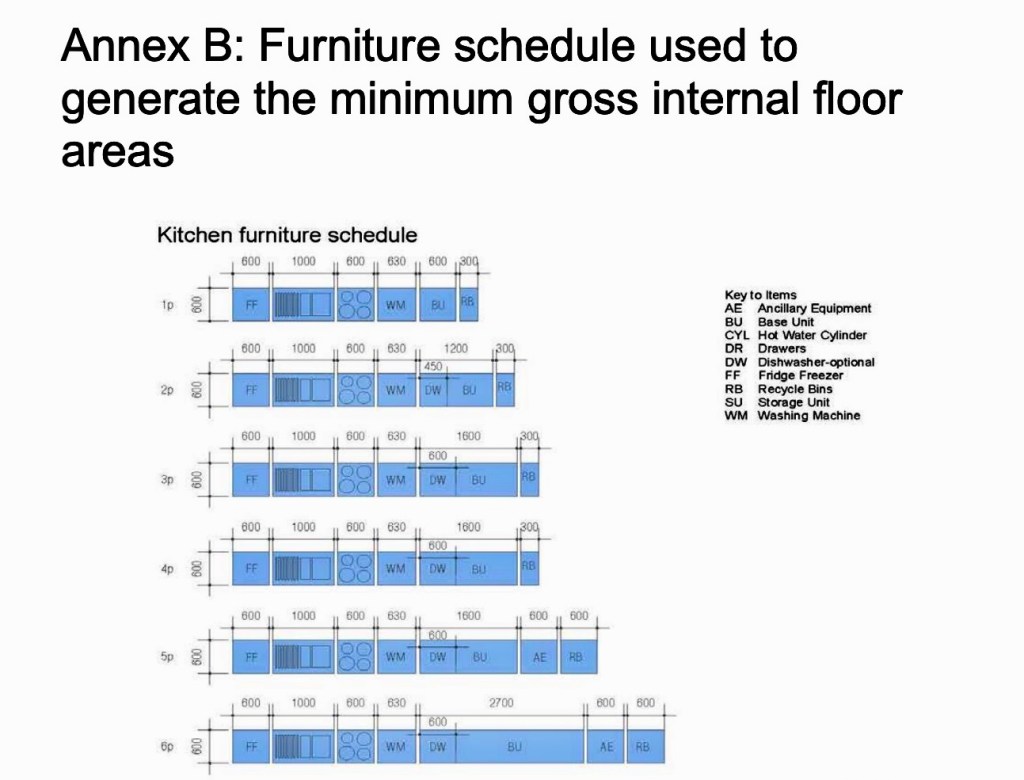

This table, derived from the UK Nationally Described Space Standard, outlines the habitability requirements for new residential developments. It specifies the minimum space required (in millimetres) for mandatory appliances and storage units in homes designed for one to six occupants, including a fridge–freezer (FF) and washing machine (WM), ensuring compliance with the minimum gross internal area standards.

What do regulations say about the minimum size of a home?

Housing standards aim to define what is “minimally habitable” from a functional standpoint, but they rarely address what the human brain actually needs to feel well.

The United States remains among the countries with the largest homes in the world, second only to Australia. The average size of a single-family house is around 201 m², and in states such as Utah it exceeds this figure by a wide margin—reflecting a strong cultural preference for space, scale, and domestic abundance.

In the United Kingdom, the Nationally Described Space Standards set a minimum of 37 m² for one person and 50 m² for two. Although homes of 20–25 m² are often mentioned in public debate, they do not represent the mainstream housing market. These are typically exceptions, conversions, or pilot projects approved under extreme housing pressure, rather than a generalised housing solution.

In Colombia, Social Interest Housing has traditionally ranged between 36 and 42 m², but in recent years even smaller units—28–32 m²—have emerged, driven largely by market pressures rather than by evidence related to wellbeing or mental health.

Meeting a regulatory minimum does not guarantee a healthy life. Wellbeing depends far more on how spaces are designed, experienced, and adapted over time than on their surface area alone.

Beyond the architectural grandeur lies the paradox of the oversized home: loneliness, high maintenance costs, and an ongoing debate about environmental sustainability.

The seduction of spatial excess

If minimal space poses an obvious problem, excess space is not without its consequences either.

Although many cultures associate size with success and quality of life, the relationship between space and wellbeing is far more complex. Large homes can offer comfort and flexibility, but they can also bring isolation, high maintenance costs, and a sense of emptiness when not fully inhabited. This contrast becomes particularly evident over time.

The “aging in place” phenomenon reveals the problem

In the United States, one of the biggest issues associated with excessively large homes emerges in later life. Many of these houses were designed for young, large families rather than older adults living alone.

While most people wish to age in their own homes, a substantial proportion of older adults remain in homes that are difficult to maintain, costly, and poorly adapted to physical and cognitive changes. What once represented stability can turn into an emotional, physical, and financial burden. Loneliness, shrinking social networks, and a lack of spatial adaptability directly impact mental health.

Organisations such as the CDC, the US’s leading public health agency, and AARP, dedicated to studying and advocating for older adults’ quality of life, have identified this as a growing challenge of the built environment.

Main problems of excessively large homes in the US when ageing

- Higher risk of falls and accidents

In the United States, falls are the leading cause of serious injuries among older adults. Stairs and level changes increase risk, yet only around 10% of homes are adapted for ageing. - Isolation and loneliness

Large houses fragment space and reduce daily contact. Many older adults live alone in homes designed for families, intensifying feelings of isolation and affecting mental health. - Physical and cognitive overload

Maintaining and moving through large areas requires constant effort, generating fatigue and stress, particularly for those with cognitive decline or dementia. - Difficulty adapting to health changes

Most of these homes do not allow simple adjustments such as ground-floor bedrooms, accessible bathrooms, or clear pathways. This limits autonomy and accelerates dependence. - Economic and emotional burden

High costs for maintenance, heating, and cooling make the home a constant source of concern, affecting its perception as a safe and restorative space.

Houses in distant suburbs and less walkable neighbourhoods increase car dependency and decrease social interaction.

The Effects of Living in Minuscule Spaces

Although reducing housing size is often associated with efficiency or sustainability, when space falls below certain thresholds, the effects on the brain and mental health can be profound.

- Crowding and overcrowding This is linked to increased psychological stress. In such cases, the brain activates threat responses, raising cortisol levels and reducing the sense of safety. A lack of visual and acoustic privacy generates conflicts and increases the risk of anxiety and depression. It is not the number of people living together that matters, but the inability to create distance.

- Cognitive fatigue Visual overload and insufficient storage create a cognitively demanding environment. The brain must constantly filter stimuli, exhausting attentional resources. This reduces concentration and disrupts rest, diminishing the sense of mental recovery even at home. The space becomes a continuous stimulus.

- Sense of lost control One of the deepest—and least visible—effects of living in overcrowded spaces is the loss of agency. When it is impossible to reorganise the environment, adjust light, noise, or space usage, a sense of environmental helplessness emerges.

Between excess and deficiency

Ultimately, the square footage crisis has taught us that wellbeing cannot be measured with a tape measure—it is reflected in how our nervous system responds to the environment. Meeting legal minimums is not enough if a space suffocates our mental health or isolates us in later life.

So, if size alone is not the answer, how can we reclaim the sense of home in an ever-shrinking world? The key may lie in what plans cannot show but our senses perceive instantly: the management of light, the effect of ceiling height, our connection with living elements, and the way the brain interprets spaciousness.

In my next article, I will explore these pillars of sensory design and how we can “hack” our perception to live better—whether in more space or less.

Recommended Readings

WHO – Housing and Health Guidelines. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550376

Environmental Psychology: Principles and Practice – Robert Gifford

Obra clave para comprender cómo el espacio, la densidad, el control ambiental y el diseño influyen en el comportamiento y la salud mental.

Evans, G. W. (2003). The Built Environment and Mental Health

Revisión clásica sobre hacinamiento, estrés ambiental y efectos psicológicos de la vivienda.

UN-Habitat – Adequate Housing

Análisis sobre densificación, vivienda mínima y sus implicaciones sociales y psicológicas a largo plazo.

Kellert, S. & Calabrese, E. – The Practice of Biophilic Design

Para profundizar en cómo la luz, las vistas y la conexión con lo natural pueden compensar —hasta cierto punto— la reducción del espacio.