The spaces we inhabit subtly shape our thoughts, emotions, and behaviours in ways we may not fully realize. From the way we navigate a city to the emotions evoked by a room, the built environment profoundly influences brain development, cognitive functions like memory, reasoning, and planning, and overall well-being.

Neuroscience and architecture are increasingly intertwined, with growing evidence that our brains respond dynamically to spatial configurations, sensory stimuli, and environmental cues. Understanding these connections is essential for architects, designers, and urban planners seeking to create spaces that enhance cognitive function, emotional balance, and overall quality of life.

The Neuroscience of Space

Our perception of space is largely dictated by brain processes that involve the parietal lobe, which integrates sensory inputs to form spatial awareness, and the prefrontal cortex, responsible for decision-making and navigation. The way we interact with our environment influences our cognitive load, memory, and emotional state.

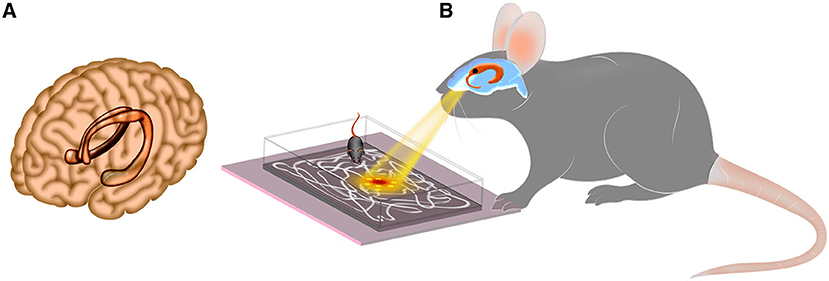

(B) When an animal moves in the space around it (gray lines in the box), a specific place cell in its hippocampus (black dot in the mouse’s hippocampus) becomes electrically active when the animal is in a specific location in the environment (orange spot in the box). This cellular activity helps the animal to build a mental map of the environment, allowing it to flexibly navigate in the world

The Role of the Hippocampus in Spatial Navigation and Memory

The hippocampus contains the place cells that play a fundamental role in spatial memory and navigation, housing place cells that help us create internal maps of our surroundings. Poorly designed spaces that lack differentiation or clear way to find cues can impair this function, causing stress and disorientation. In contrast, environments with distinct landmarks and varied spatial layouts support better memory retention and ease of movement.

A significant study on this subject involved London taxi drivers. Conducted by neuroscientist Eleanor Maguire and her team, the research found that London cab drivers, who undergo rigorous training to memorise the city’s complex layout known as “The Knowledge”, have developed a larger hippocampus than the average person.

Brain scans revealed that their posterior hippocampus—associated with spatial navigation—grew over time in response to their experience. This provided one of the first clear pieces of evidence that the human brain physically adapts to the demands of the environment, demonstrating the profound impact that way finding and navigation can have on brain structure.

The hippocampus plays a critical role in spatial navigation and memory, adapting structurally in response to experience, as seen in London taxi drivers. This insight is particularly relevant in understanding Alzheimer’s disease, where hippocampal damage leads to severe disorientation and difficulties with navigation. As the disease progresses, individuals struggle with spatial awareness, getting lost even in familiar environments, highlighting the importance of the hippocampus in maintaining cognitive maps.

When drunk, the hippocampus becomes less efficient, resulting in memory lapses, confusion, difficulty navigating, and impaired decision-making. The more alcohol consumed, the greater the level of impairment.

Neuroplasticity: How the Environment Shapes the Brain

Neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to reorganise itself in response to experiences—demonstrates that our surroundings have long-term impacts on cognitive abilities. Enriched environments with ample natural light, diverse textures, and adaptable spaces enhance mental stimulation, whereas deprived environments can lead to cognitive stagnation and stress.

How Architecture Affects the Brain

Sensory processing in built environments is fundamental to how our brain interprets and responds to our surroundings, shaping our emotions, behaviours, and cognitive functions. Our senses—sight, sound, touch, smell, and proprioception—constantly gather information, allowing the brain to assess safety, comfort, and usability. A well-balanced environment that regulates sensory stimuli enhances focus, reduces stress, and promotes overall well-being. Conversely, spaces with excessive noise, harsh lighting, or overwhelming stimuli can lead to cognitive fatigue, anxiety, and difficulty concentrating.

Beyond influencing our mental state, sensory processing also helps us navigate spaces effectively. Our brain integrates sensory cues to understand spatial orientation, recognize landmarks, and move efficiently within an environment. However, for neurodivergent individuals, such as those with autism or ADHD, sensory input may be heightened or diminished, making navigation challenging in overstimulating or poorly designed spaces. Thoughtful design—incorporating clear way finding, acoustic control, and sensory-friendly materials—supports intuitive navigation, enhances comfort, and creates inclusive environments that accommodate diverse cognitive needs.

Sensory Processing and Built Environments

1. The Effect of Light, Colour, and Texture on Cognition

Natural light regulates circadian rhythms, improving mood and cognitive performance. Colour psychology suggests that warm hues stimulate energy, while cooler tones encourage relaxation. Texture and materiality, such as soft furnishings or natural wood, contribute to sensory comfort and well-being.

Neurodivergent individuals, such as those with autism or ADHD, often process sensory information differently. An overly stimulating environment—through excessive noise, clutter, or harsh lighting—can be distressing for them. Conversely, spaces that are too sterile or monotonous may lack the necessary engagement to support cognitive function.

2. The Role of Acoustics, Lighting, and Materiality

Acoustic design helps reduce noise pollution, which can otherwise contribute to stress and distraction. Adjustable lighting allows for individual sensory preferences, while materials with varied textures create a more engaging and comfortable environment.

Designing inclusive spaces enhances well-being and functionality for neurodivergent individuals. Autism-friendly schools benefit from quiet zones, clear way finding, and soft lighting to reduce sensory overload. ADHD-supportive workspaces thrive with flexible seating, movement-friendly layouts, and fidget-friendly elements that promote focus. For dementia-inclusive design, familiar spatial layouts, high-contrast elements, and easy-to-navigate paths improve orientation and independence. Thoughtful architectural choices can create environments that support diverse cognitive needs, fostering comfort, accessibility, and productivity for all.

3. The Role of Natural Elements to Support Cognitive Function and Reduce Stress

Research shows that exposure to nature within spaces can lower cortisol levels, enhance creativity, and improve cognitive function, contributing to overall well-being. Biophilic design is an approach that incorporates natural elements—such as plants, water, and sunlight—into built environments to strengthen the human-nature connection.

Key natural elements play distinct roles in shaping our mental and emotional state. Greenery boosts focus, reduces stress, and uplifts mood, while water features promote relaxation and mental clarity. Natural light regulates circadian rhythms, increasing alertness and productivity throughout the day.

Biophilic design enhances environments for neurodivergent individuals by incorporating nature, such as indoor gardens in offices that aid focus for those with ADHD and sensory sensitivities, and hospital views that accelerate recovery and lower anxiety for autistic individuals. Urban parks and rooftop gardens also promote community well-being, reduce stress, support emotional regulation, and encourage social connections among diverse neurological populations.

How Urban Spaces affect Mental Health

Urban spaces play a crucial role in shaping mental health by influencing stress levels, cognitive function, and overall emotional well-being. Well-designed cities that integrate green spaces, accessible public areas, and pedestrian-friendly layouts encourage relaxation, social interaction, and physical activity, all of which are essential for maintaining mental health. Access to nature within urban environments has been shown to reduce cortisol levels, improve mood, and enhance concentration, benefiting neurodivergent individuals and the broader population alike.

On the other hand, poorly designed urban spaces can contribute to mental distress. Overcrowding, noise pollution, and a lack of natural elements often lead to increased anxiety, depression, and cognitive fatigue. Environments that lack sensory-friendly spaces can be overwhelming for neurodivergent individuals, exacerbating stress and social isolation. Thoughtful urban planning that incorporates biophilic design, quiet zones, and accessible infrastructure can create inclusive, supportive cities that foster psychological resilience and enhance overall well-being for all residents.

The Importance of Inclusive and Restorative Urban Spaces

1. Walkable cities

Walkable cities with intuitive way finding reduce stress by providing residents and visitors with clear navigation paths, ensuring a more pleasant and efficient travel experience while promoting physical activity and enhancing community interaction.

2. Sensory-friendly public spaces

Sensory-friendly public spaces accommodate neurodivergent individuals, providing soothing environments with reduced sensory overload, such as soft lighting, quiet areas, and minimal distractions, which allow for greater comfort and inclusivity for all visitors.

3. Community-driven spaces

Community-driven design fosters a profound sense of belonging and safety, encouraging individuals to connect and collaborate with one another in meaningful ways, ultimately creating a supportive environment that nurtures growth and resilience.

Possibly in the future, smart spaces will adjust to our thoughts and feelings using AI for lighting, sound, and design. By reacting to real-time input, they will help us concentrate, lower stress, and combine technology with human experience.

Future Directions: Designing for Cognitive Well-being

With advances in AI, architects can now analyse cognitive and emotional responses to spaces, optimising environments for better well-being. Neuro-architecture integrates EEG and biometric feedback to refine spatial designs that enhance focus, relaxation, or social engagement.

Smart Spaces That Adapt to Cognitive and Emotional Needs

Smart spaces are revolutionizing how environments adapt to cognitive and emotional needs, enhancing comfort and well-being. Adaptive lighting and acoustics respond to user preferences, reducing sensory overload and improving focus. AI-powered environments dynamically adjust layouts based on cognitive workload, optimizing productivity and reducing stress. Wearable technology provides real-time feedback on environmental stressors, allowing spaces to personalize settings for individual needs. By integrating these innovations, smart spaces create more inclusive, responsive environments that support diverse cognitive and emotional experiences.

The Importance of Participatory Design

User-centred design ensures that people of all cognitive and sensory backgrounds are considered, fostering inclusivity and accessibility. By prioritizing the needs and preferences of diverse user groups, designers can create environments that accommodate various abilities and enhance the overall experience.

Engaging communities in design processes not only results in spaces that are both functional and emotionally enriching, but also empowers individuals by giving them a voice in shaping their surroundings, cultivating a sense of ownership and belonging. This collaborative approach leads to innovative solutions that reflect the unique characteristics of each community, ultimately promoting well-being and social interaction among users.

Conclusion

Architecture is not merely about aesthetics; it fundamentally shapes human cognition, behaviour, and well-being. By integrating neuroscience, sensory design, and biophilic principles, architects and urban planners can create spaces that support mental clarity, emotional regulation, and social harmony. The future of design must prioritize inclusivity, adaptability, and evidence-based strategies to ensure environments that enhance—not hinder—human potential.

Call to Action: How can we make our homes, workplaces, and cities more cognitively supportive? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments below!

References

Tribute to pioneering cognitive neuroscientist Professor Eleanor Maguire https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2025/jan/tribute-pioneering-cognitive-neuroscientist-professor-eleanor-maguire

Operability of Smart Spaces in Urban Environments: A Systematic Review on Enhancing Functionality and User Experience https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/23/15/6938?utm_source=chatgpt.com

A sense of place https://thebiologist.rsb.org.uk/biologist-features/what-when-and-where

Place Cells: The Brain Cells That Help us Navigate the World https://kids.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frym.2023.1022498

How BEER damages the brains of teenagers: Alcohol ‘impairs spatial awareness and memory’ https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-3416251/How-BEER-damages-brains-teenagers-Alcohol-impairs-spatial-awareness-memory.html

Neuroarchitecture: How Your Brain Responds to Different Spaces https://www.archdaily.com/982248/neuroarchitecture-how-your-brain-responds-to-different-spaces#:~:text=Articles,Brain%20Responds%20to%20Different%20Spaces

Neuroarchitecture: When the Mind Meets the Built Form. https://www.rockfon.co.uk/about-us/blog/2023/neuroarchitecture/#:~:text=What%20is%20Neuroarchitecture?,Access%20to%20art%20and%20nature

The Embodiment of Architectural Experience: A Methodological Perspective on Neuro-Architecture https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/human-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2022.833528/full

Designing for human wellbeing: The integration of neuroarchitecture in design – A systematic review https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2090447922004130

Learn the Knowledge of London. https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/taxis-and-private-hire/licensing/learn-the-knowledge-of-london

How Does the Brain Know Where We Are? https://kids.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frym.2020.00059

London taxi drivers: A review of neurocognitive studies and an exploration of how they build their cognitive map of London. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/hipo.23395#:~:text=Licensed%20London%20taxi%20drivers%20have,to%20efficiently%20learn%20new%20environments.