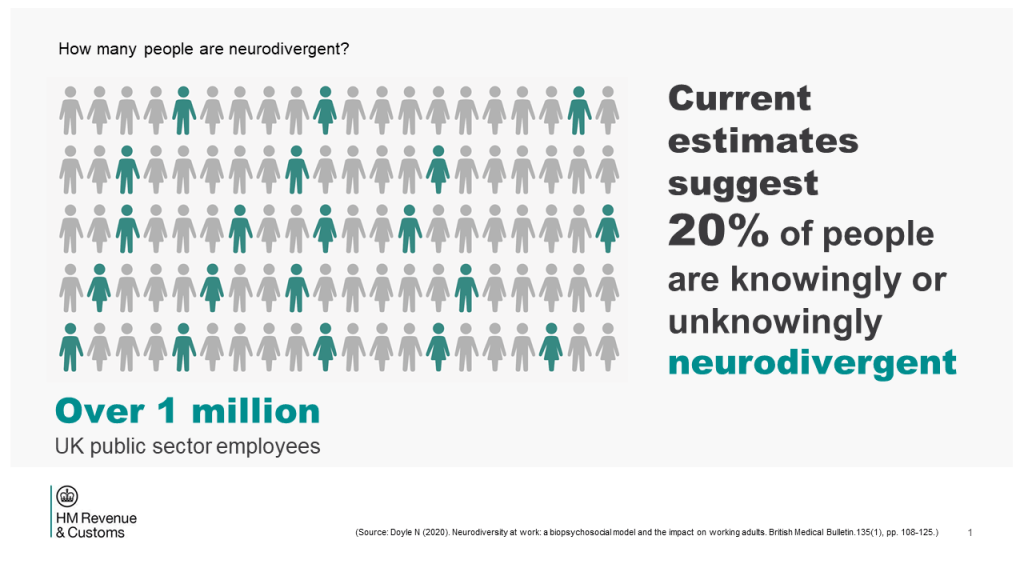

Neurodiversity Celebration Week, observed annually from 17 to 23 March, is a global movement that shifts the perspective on neurological differences. Rather than viewing conditions such as autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and dyspraxia as deficits, neurodiversity recognises them as natural variations in human cognition. This week serves as a powerful reminder to embrace inclusion, foster understanding, and rethink how our environments can support diverse ways of thinking, processing, and interacting with the world.

The term neurodiversity, coined by sociologist Judy Singer in the late 1990s, challenges the traditional view that neurological differences—such as autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and dyspraxia—are deficits. Instead, it recognises them as natural variations in human thinking.

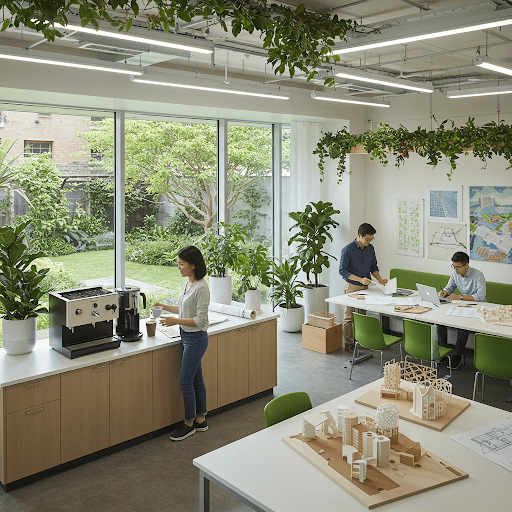

A critical aspect of inclusion lies in how we design our spaces. Neuroarchitecture, an emerging field that applies neuroscience insights to architecture, offers a transformative approach to creating built environments that promote well-being, focus, and accessibility for all cognitive styles.

The Impact of Neuroarchitecture on Inclusion

Traditional architectural designs often prioritise neurotypical experiences, neglecting the sensory, cognitive, and emotional needs of neurodivergent individuals. By integrating neuroarchitectural principles, we can create spaces that:

✅ Reduce stress and anxiety

✅ Enhance wellbeing, concentration, and creativity

✅ Provide adaptable environments that cater to individual sensory needs

Key Strategies for Designing for Neurodiversity

1. Sensory-Friendly Environments

Neurodivergent individuals regularly experience heightened sensory sensitivities, making environmental factors such as lighting, sound, textures, and spatial arrangements either supportive or overwhelming.

Natural Light & Biophilic Design

- Research shows that natural light boosts mood, reduces stress, and enhances cognitive performance.

- Large windows, skylights, and indoor greenery can create a calming atmosphere.

Acoustic Considerations

- Soundproofing, quiet zones, and noise-absorbing materials help individuals sensitive to noise.

- Workspaces and schools should provide areas with varied noise levels, enabling people to choose the setting that best suits them.

2. Flexible & Adaptable Spaces

Rigid environments can be stress-inducing for neurodivergent individuals. Creating flexible spaces empowers individuals to modify their surroundings to fit their needs.

Zoned Workspaces

- Offices and schools should incorporate:

✅ “Quiet zones” for focused tasks

✅ “Collaborative zones” for teamwork - This gives individuals autonomy over their sensory environment.

Modular Design

- Moveable walls, adjustable lighting, and customisable furniture allow users to personalise their space according to their comfort and task requirements.

3. Way finding & Visual Clarity

Navigation can be challenging for individuals with spatial processing differences. Clear and intuitive way finding reduces cognitive load and enhances confidence.

- Simple, well-lit signage with high-contrast colours helps with navigation.

- Distinct landmarks make spaces more intuitive and easier to remember.

- Minimising visual clutter helps individuals with attention-related challenges stay focused.

4. Emotional & Psychological Safety

A well-designed space can foster a sense of security and calm. This is especially important for neurodivergent individuals, who may experience higher levels of anxiety in overstimulating environments.

Soothing Colour Schemes

- Muted tones and natural hues can reduce sensory overload and create a relaxing ambiance.

- Vibrant colours should be used selectively to highlight significant features without overwhelming the senses.

Breakout & Retreat Spaces

- Schools and offices should provide quiet, private spaces where individuals can retreat when feeling overwhelmed.

- These can be designed with soft lighting, comfortable seating, and sound-dampening features.

Case Study: The Sainsbury Wellcome Centre

A powerful example of neuroarchitecture in practice is the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre (SWC) in London. Designed by Ian Ritchie Architects, the project was informed by a full year of research into how the built environment affects the brain. Every element of the design—from natural lighting and spatial flow to social areas and quiet zones—was carefully considered to support cognitive function, reduce stress, and foster creativity.

The building was specifically created to house a neurodiverse community of world-class neuroscientists, providing a space that enhances both individual focus and collaborative interaction. By integrating principles from neuroscience into its architecture, the centre demonstrates how design can actively support brain health, productivity, and well-being.

More than just a research facility, the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre stands as a model for future workplaces and learning environments—one where the design itself becomes a tool for unlocking human potential.

The Wellcome Sainsbury Centre demonstrates how scientific research and architectural design can work together to support different cognitive styles.

Conclusion

As we reflect on Neurodiversity Week, one thing becomes clear: inclusive design isn’t just beneficial for neurodivergent individuals—it enhances the experience for everyone. Neuroarchitecture provides us with the tools to create environments that reduce stress, boost productivity, and foster well-being. By integrating sensory-friendly elements, flexible spaces, intuitive navigation, and calming aesthetics, we can ensure that workplaces, schools, and public spaces support diverse cognitive needs.

Embracing neurodiverse design isn’t just a step toward accessibility—it’s a step toward a more innovative, empathetic, and high-performing society. When we design spaces that work for all minds, we unlock the full potential of every individual.

Call to Action: Shape the Future of Inclusive Design

🌟 For Architects & Designers: Rethink your approach to space—integrate neuroarchitectural principles into your projects. Small changes, like better lighting, adaptable workspaces, and intuitive way finding, can make a profound impact.

🏢 For Employers & Educators: Advocate for neurodiverse-friendly environments. Support policies that allow flexibility, quiet spaces, and choice in work or study settings. A more inclusive space is a more productive one.

👥 For Everyone: Raise awareness. Share the importance of neurodiverse design in your workplace, school, or community. Encourage discussions on how spaces can be improved to support every cognitive style.

This Neurodiversity Week, let’s move beyond awareness into action. Challenge the existing state of affairs, advocate for better environments, and help build a world where every mind thrives.

💡 What’s one change you can make today to support neurodiversity in your space? Let’s start the conversation. Together, we can design a future where everyone belongs. 💙

References

Neuroarchitecture: How the Perception of Our Surroundings Impacts the Brain. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-7737/13/4/220

Ian Ritchie Architects: The Wellcome Sainsbury Centre https://www.ritchie.studio/projects/sainsbury-wellcome-centre/

Sainsbury Wellcome Centre: our building https://www.sainsburywellcome.org/web/content/our-building

The Challenges of Sensory Overload: Successfully Managing Noise Overstimulation in Recovery https://www.intherooms.com/home/iloverecovery/all/the-challenges-of-sensory-overload-successfully-managing-noise-overstimulation-in-recovery/

How To Manage (and Even Overcome) Sensory Overload https://health.clevelandclinic.org/sensory-overload