“Walking is man’s best medicine.”

Hippocrates

As a tourist on the island of Mykonos, I hold a vivid memory of its narrow alleyways, whitewashed buildings, and cascading bougainvillea. The absence of cars turns every stroll into a true delight, fostering an intimate connection with the architecture and local life. A rich sensory experience that leaves a lasting impression on the memory.

Now picture yourself in a lively town square: children laughing as they play, elders chatting on benches, the scent of fresh bread wafting from a nearby bakery. The pace is gentle. The air is clean. Everything you need is just a short walk away.

Now contrast that with the reality of a six-lane highway cutting through a modern suburb—filled with noise, danger, and disconnection. In many cities, walking has become not just inconvenient, but unsafe.

Reclaiming walkability isn’t about nostalgia or charm. It’s a global necessity—for public health, safety, equity, and sustainability. In an era marked by climate crisis and social fragmentation, the walkable city isn’t just possible. It’s essential.

The Power of Walking: A Natural Human Need

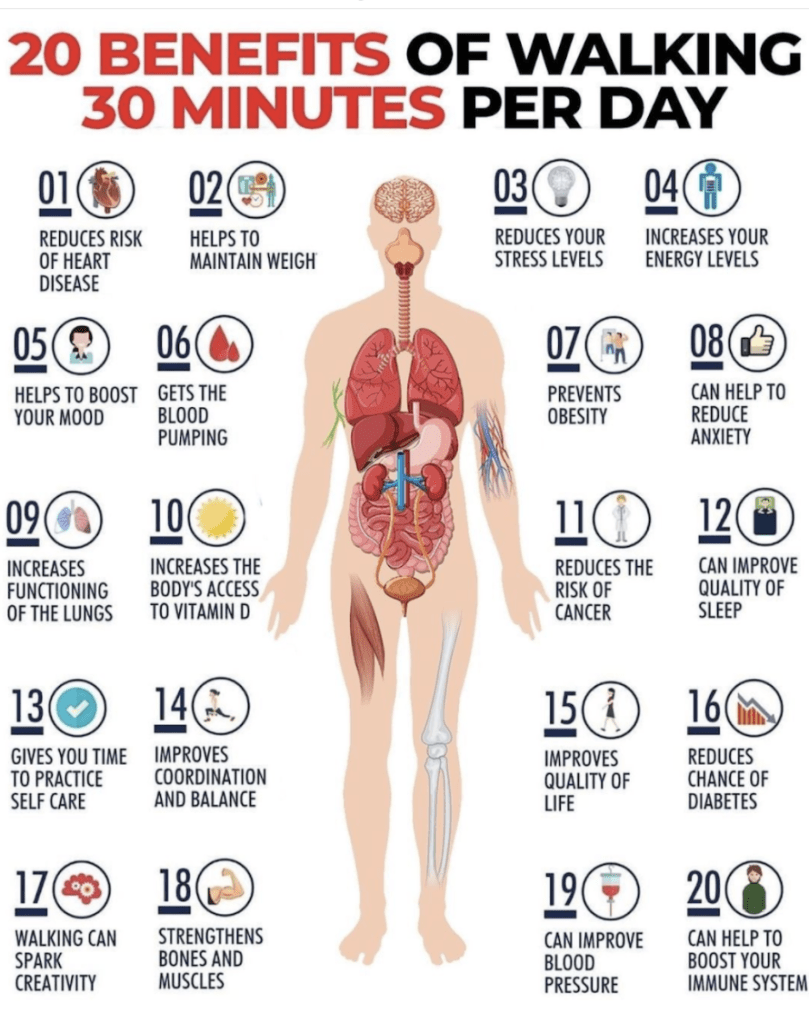

Walking is one of the most accessible and beneficial forms of physical activity. It helps prevent chronic diseases, improves cardiovascular health, and supports healthy ageing. Just as importantly, walking supports mental wellbeing—reducing stress, easing anxiety, and offering space for reflection or social connection.

When we walk through vibrant, human-scaled environments, our senses engage. We notice the seasons changing, we greet neighbours, we feel part of a place. This natural rhythm of movement helps ground us in the present, in community, and in the physical world.

A Brief Stroll Through History

In ancient cities, life was organised around the pedestrian. Markets, temples, forums, and public baths were all accessible by foot. The streets were places of commerce, dialogue, and civic life.

In Ancient Greece, Aristotle, following the tradition of his teacher Plato, founded the Peripatetic School of philosophy, named after the Greek word peripatetic, meaning “to walk about.” Lessons and dialogues often took place while walking through shaded colonnades. This tradition illustrates how physical movement and intellectual exploration have long been intertwined.

On the right, a recreation of a plaza in Ancient Rome, reflecting public life and commerce in walkable settings.

Medieval towns, with their narrow winding lanes and central plazas, continued this tradition of walkable urbanism. These cities were built before the car and are still celebrated for their human scale, charm, and spatial intimacy. The public spaces, like market squares, were vital for commerce and community life, fostering a strong sense of belonging.

These historical models show that urban life once prioritized proximity, community, and experience—values we can and should reclaim. By embracing the lessons of the past, we can create rich urban landscapes.

The Decline of the Walkable City

The 20th century saw a dramatic shift. The rise of the automobile, suburbanisation, and zoning policies fragmented cities. Functions were separated: homes in one zone, schools, and shops in another, workplaces far away. Roads widened, pavements shrank, and cars took over.

In car-oriented cities, walking is often seen negatively, associated with poverty and neglect, especially in areas lacking pedestrian infrastructure. This detrimental perception fosters social divides, creating a rift between those who can afford to drive and those who must rely on their feet. Such attitudes diminish the social status of pedestrians and undermine the development of healthier lifestyles, as people are discouraged from engaging in physical activity due to the stigma attached to walking.

Reframing walking as a dignified choice is essential for promoting inclusion and equity in urban culture.

Additionally, the absence of safe, well-maintained pavements and pedestrian-friendly spaces deters individuals from choosing walking as a viable mode of transportation, further entrenching the reliance on cars and perpetuating cycles of exclusion and health disparities. By failing to recognize walking as a legitimate and valuable means of mobility, cities risk losing the opportunity to cultivate inclusive environments that promote the well-being of all citizens.

Walkable vs. Car-Oriented Cities: Why the Shift Matters

Health & Wellbeing

Car-dominated cities lead to sedentary lives, stress from traffic, and constant exposure to pollution and noise. In contrast, walkable environments promote daily activity, cleaner air, safer streets, and healthier communities.

Environmental Impact

Walkable cities reduce emissions, decrease the urban heat island effect, and consume less land. They offer a direct response to the climate crisis by lowering our dependence on fossil fuels.

Climate Resilience

Walkable cities are better equipped to adapt to extreme weather and energy disruptions. Their compact, green design helps reduce heat, manage flooding, and maintain mobility during crises.

Equity & Inclusion

Car-oriented planning disproportionately affects the most vulnerable—children, the elderly, people with disabilities, and low-income communities. Walkable cities ensure access and dignity for all.

Economic Vitality

Foot traffic fuels small businesses. Walkable neighbourhoods see higher property values, increased tourism, and more vibrant local economies.

“Streets and their sidewalks, the main public places of a city, are its most vital organs.”

Jane Jacobs

On the right, A vibrant pedestrian-friendly space in Poblenou Superblock in Barcelona, showcasing the benefits of walkable urban design.

Case Studies: Designing Walkability Back into Cities

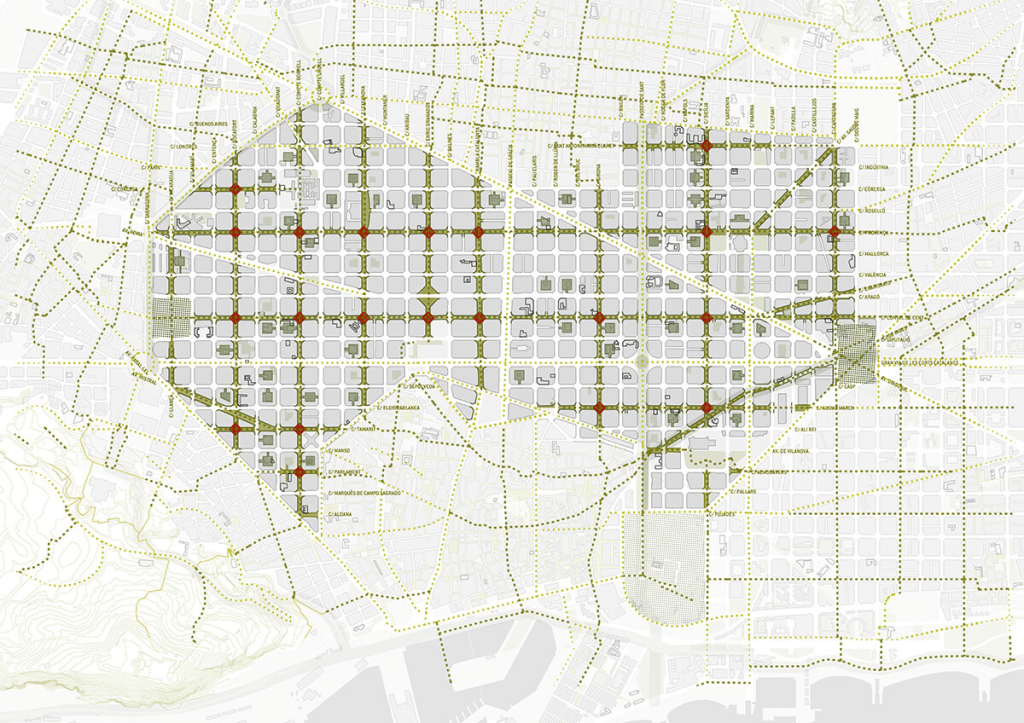

Barcelona, Spain – Superblocks (Superilles)

Barcelona’s Superblocks reroute traffic around clusters of streets, creating interior zones for pedestrians, cyclists, play, and greenery. This model has reduced air pollution, increased public space, and revitalised neighbourhood life.

On the right, A vibrant street scene in Paris featuring quaint cafés, shops, and bicycle stands, exemplifying a pedestrian-friendly environment.

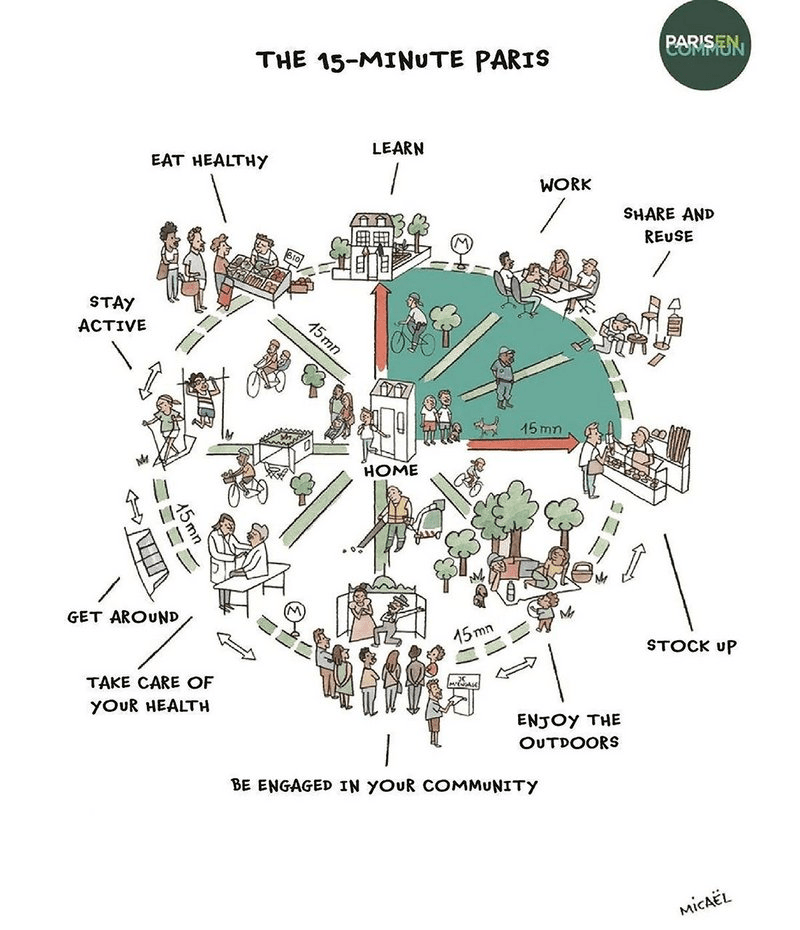

Paris, France – The 15-Minute City

In Paris, the 15-minute city concept ensures that all essential services—schools, shops, clinics, parks—are within a 15-minute walk or cycle ride. Car lanes have been converted into bike lanes, and public spaces have been reimagined to serve communities.

Principles of a Walkable City

- Proximity: Mixed-use neighbourhoods where daily needs are nearby.

- Connectivity: Safe, continuous pedestrian paths linked to public transport.

- Safety: Traffic calming, clear crossings, lighting, and surveillance.

- Comfort & Beauty: Shaded pavements, benches, greenery, and aesthetic street scapes.

- Equity: Universal design for all ages and abilities.

- Participation: Involving residents in co-designing public space.

Urban Tactics for Transformation

- Tactical urbanism: quick, low-cost street improvements like pop-up bike lanes and parklets.

- Car-free days and pedestrian zones.

- Zoning reforms to allow for mixed-use development.

- Community-led walkability audits.

This isn’t utopia—it’s the logical result of designing for people over cars.

Walkable cities connect us—to our bodies, to each other, and to the Earth. They heal the fractures caused by car dependence, creating healthier, more equitable, and more vibrant communities.

The walkable city is not a utopia of the past—it is a blueprint for the future. And it’s a future we can start building today, one step at a time.

Let’s reclaim our streets. Let’s walk into a better world.

References

Sustainable cities: The Daunting Challenge of Unwalkable America https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/ex/sustainablecitiescollective/daunting-challenge-unwalkable-america-excerpted-people-habitat/333351/

Planning for walkable cities in Africa: Co-producing knowledge on

conditions, practices, and strategies. https://www.walkingcitieslab.com/_files/ugd/b4aba8_838848828b4c43e8951bba5a9fe6b035.pdf

Barcelona’s Superblocks and Green Axes, a Pathway Towards a More Sustainable City https://www.gabarcelona.com/blog/superblocks/

The Negative Consequences of Car Dependency https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2015/1/20/the-negative-consequences-of-car-dependency

Car-Free Livability Program in Oslo https://pedestrianspace.org/car-free-livability-program-in-oslo/

UN Sustainable Development Goals: Goal 11: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/

Walking for health https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise/walking-for-health/

The “15-minute city”: how Paris is turning density and lack of space into a strength. https://sustainableurbandelta.com/15-minute-city-paris-urban-farms/

Why has the ‘15-minute city’ taken off in Paris but become a controversial idea in the UK? https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2024/apr/06/why-has-15-minute-city-taken-off-paris-toxic-idea-uk-carlos-moreno

Carlos Moreno: 15 minutes to save the world https://www.ribaj.com/culture/profile-carlos-moreno-15-minute-city-obel-award-planning

One thought on “Streets for People: The Case for Walkable Cities”