Brutalism was more than a style of raw concrete and bold forms—it was an experiment in shaping society through design. Emerging from the devastation of the Second World War, it promised dignity, efficiency, and fairness in housing and public life. Buildings were stripped back to their essentials, constructed in béton brut—raw concrete—without ornament or disguise.

From the perspective of neuroarchitecture, Brutalism is especially revealing. It shows how scale and materiality affect human experience: in theatres, museums, and universities, monumentality inspired awe and civic pride; in housing estates, the same monumentality often became a burden, overwhelming daily life and disrupting familiar routines.

Brutalism, therefore, should not be understood only as an architectural movement, but as a case study of how environments shape perception, emotion, wellbeing, and the sense of acceptance among those who inhabit them.

What uplifts in a theatre can overwhelm in a dwelling.

Brutalist housing estates were built with the promise of dignity and community, yet in many cases they failed residents. Monumentality that inspired awe in public buildings became a pitfall in housing—disrupting daily rituals, isolating neighbours, and leaving people feeling overwhelmed rather than at home.

1. Honesty in Materials

The term Brutalism comes from Le Corbusier’s expression béton brut. Concrete was not chosen to provoke controversy, but because it was affordable, durable, and expressive. Architects employed techniques such as board-marking, which left the imprint of timber on the surface, or hammering that revealed the material’s texture. By leaving the structure exposed, these marks recorded the very act of building, transforming the construction into tangible memory.

Lesson: Materials can tell the truth. When architects allow structure and process to remain visible, buildings become more than shelters—they become narratives of how things are made.

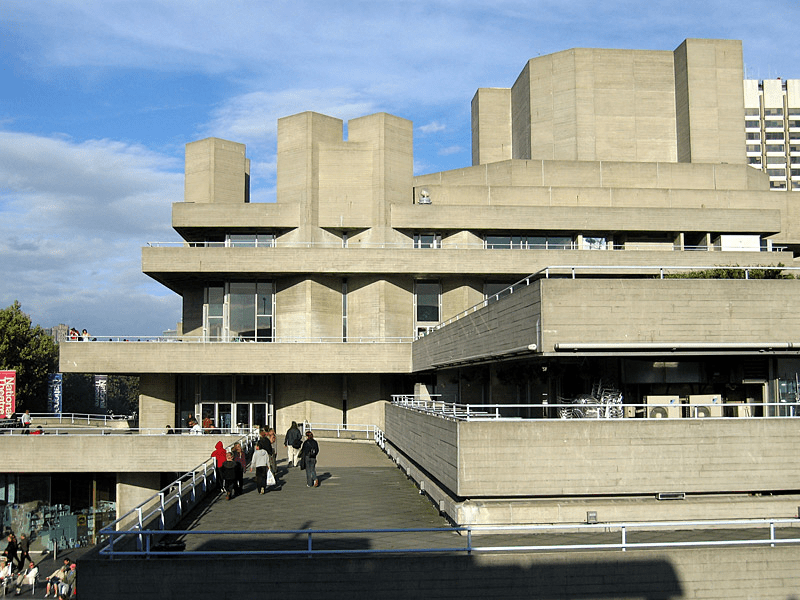

In this landmark, large scale feels inviting rather than overwhelming—its layered terraces and open foyers connect seamlessly with public space and the river Thames, transforming monumentality into one of London’s most iconic and cherished public places.

From the outside, its bold terraces rise in sculptural layers; inside, warm foyers and open circulation areas reveal how monumentality can also feel human and welcoming. Photo by Philip Vile.

2. Architecture for Community

Brutalism was conceived as social modernism in concrete. Its most ambitious projects were not luxury developments, but housing estates, schools, universities, and libraries. The Barbican in London, Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre, and Basil Spence’s University of Sussex halls aimed to create environments where people could live, learn, and gather. Many integrated gardens, kindergartens, or cultural spaces.

But here, scale became decisive.

- In civic buildings, monumentality worked: dramatic terraces and sculptural masses inspired collective pride.

- In housing, monumentality often failed: towers and vast blocks replaced the intimacy of streets and doorsteps with lifts, corridors, and communal areas far from daily life.

For many families, used to low-rise homes where neighbours greeted one another outside, the sudden move to high-rise towers felt disorienting. Everyday rituals were lost. Residents felt less in control of their environment—and less at home.

Lesson: Community architecture must balance the monumental with the human.

3. Facing Criticism

By the 1970s, Brutalism was under attack:

- Harsh aesthetics: grey façades and rough surfaces were considered cold and alien.

- Decay and neglect: without maintenance, concrete stained, cracked, and weathered badly.

- Associations with failure: underfunded estates became linked with poverty and crime, and the buildings were blamed.

- Loss of control: residents felt dwarfed by towers, trapped in lifts, and disconnected from street life.

These criticisms reveal not only material shortcomings, but psychological ones. Scale, circulation, and sensory cues directly affect how safe, comfortable, and empowered people feel.

Lesson: Architecture cannot succeed without social and psychological care. Design, maintenance, and context matter as much as structure.

Le Corbusier’s sculptural chapel, where thick concrete walls, sweeping rooflines, and dramatic light turn monumentality into a deeply human and spiritual experience.

Designed by Oscar Niemeyer, this landmark of modernist Brutalism unites efficiency and sculpture—twin towers flanked by a concave and a convex dome, where concrete becomes both monument and symbol of democracy.

4. Preservation and Reappraisal

Decades later, Brutalism is being reassessed. The Barbican Estate is now celebrated as a cultural landmark; the National Theatre is admired for its sculptural honesty; Trellick Tower has become a protected icon. Campaigns around the world fight to preserve endangered Brutalist structures such as Robin Hood Gardens.

Cultural attitudes have also shifted. Today, high-rise living is far more common than in the 1950s, and younger generations—raised in dense cities—often see these buildings as bold rather than alienating. On social media, Brutalist silhouettes and textures are reframed as sculptural art. A “neo-Brutalist” trend is emerging, reinterpreting raw concrete and exposed structure with contemporary ideas of sustainability and comfort.

Lesson: Perceptions evolve. Monumentality once seen as oppressive can later be admired as inspiring. Architecture’s meaning is never fixed—it changes with time, memory, and cultural context.

5. Lessons for the Future

Brutalism still speaks powerfully today, offering lessons that extend well beyond concrete:

- Material honesty: Authenticity resonates, but it must be balanced with sensitivity to perception and comfort.

- Community focus: Design should nurture shared life, not only private units.

- Courage in design: Architecture that provokes debate frequently leaves the deepest legacy.

- Maintenance matters: Without care, even the strongest structures decline.

- Sustainability through reuse: Adapting Brutalist buildings is more ecological than demolition.

Scale is both spatial and emotional. It decides whether we feel empowered or diminished, connected or isolated.

Scale and Neuroarchitecture – the central lesson

Monumentality can enrich civic spaces, inspiring awe, pride and belonging. But in housing, monumentality without intimacy can erode identity and wellbeing. From a neuroarchitectural perspective, scale is never neutral: it shapes how we feel, how we interact, and how much control we sense over our lives. Brutalism demonstrates that architecture is not only about shelter—it is about psychology, agency, and the rhythms of everyday life.

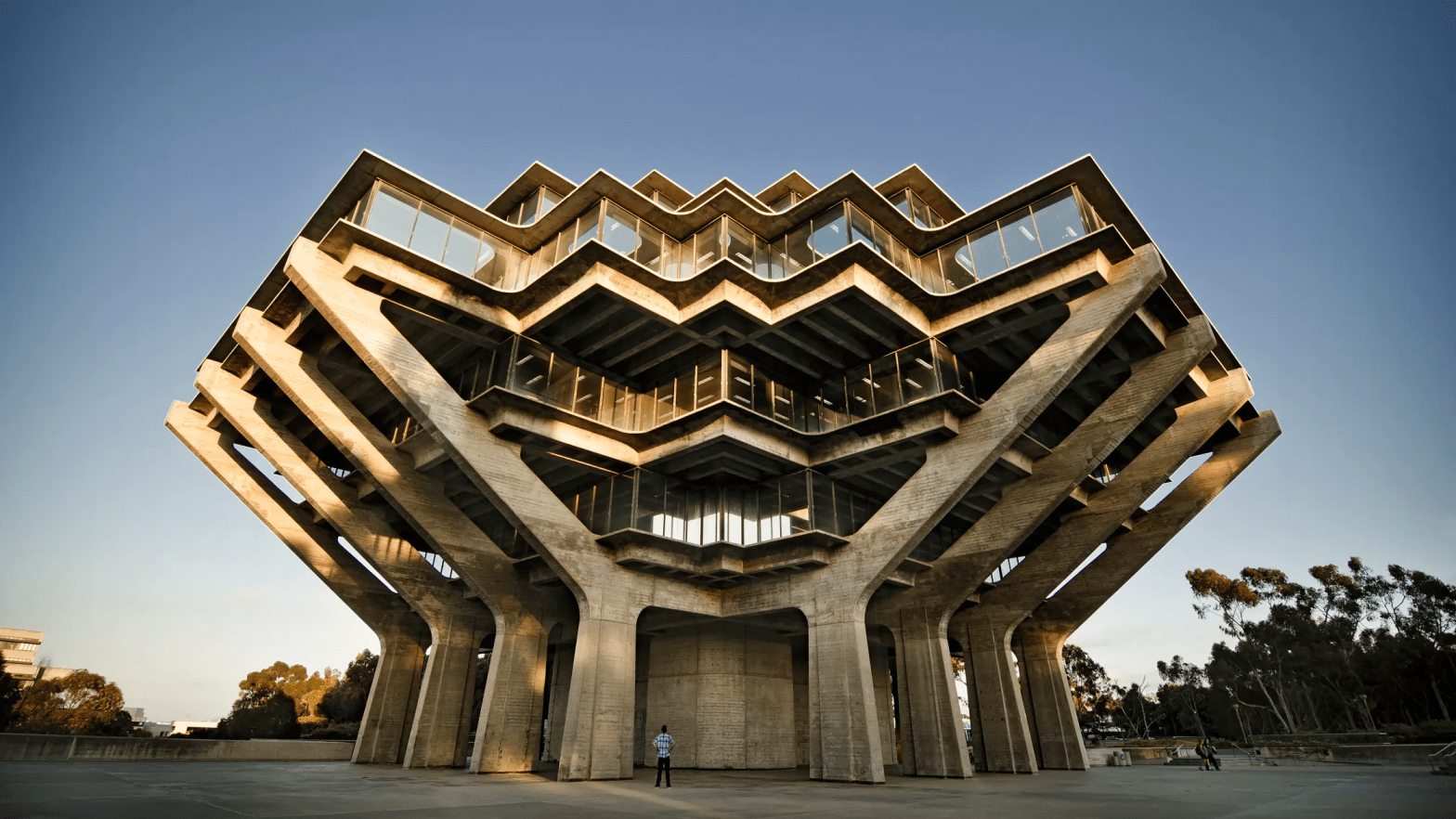

A masterpiece of Brutalism by William Pereira, where sculptural concrete and daring monumentality turn a library into an emblem of knowledge and civic pride.

An icon of Brutalism in South America: monumental in its concrete and bold geometries on the exterior, yet surprisingly dynamic inside, where light and scale transform the experience of space. Photo: Federico Cairoli.

Conclusion: Learning from Brutalism

Brutalism was not simply a style—it was an experiment in rebuilding life at scale. In public buildings, its monumentality inspired civic pride. In housing, the same monumentality frequently became a pitfall, disrupting the familiar rituals of daily living.

This paradox offers Brutalism’s most enduring lesson for neuroarchitecture: scale is both spatial and emotional. It governs whether we feel empowered or diminished, connected or isolated.

As we face today’s challenges of housing, inequality, and climate change, Brutalism confronts us with a question that is as urgent now as it was then:

If architecture can inspire but also overwhelm—empower but alienate—how will we design the next generation of cities to be bold, inclusive, and profoundly human?

References

Banham, R. (1966). The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic? London: Architectural Press.

Forty, A. (2012). Concrete and Culture: A Material History. London: Reaktion Books.

Goldhagen, S. W. (2017). Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives. New York: Harper.

Küller, R., Ballal, S., Laike, T., Mikellides, B., & Tonello, G. (2006). The impact of light and colour on psychological mood: A cross-cultural study of indoor work environments. Ergonomics, 49(14), 1496–1507.

RIBA. (n.d.). Brutalism. Royal Institute of British Architects. Retrieved from https://www.architecture.com/explore-architecture/brutalism

Saint, A. (2018). Brutalism: An Architecture of Exhilaration. London: Historic England.

Brutalism: controversy, criticism, and revival of a controversial style. https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/architectural-styles/a10716-brutalism-controversy-criticism-and-revival-of-a-controversial-style/

0 Iconic Brutalist Buildings You Should Know. https://monograph.com/blog/brutalist-buildings