Liam is five. On his first day at a new school, he didn’t sit where instructed or follow the routine. Instead, he moved constantly—reading every sign, poster, and label in sight, not just in the corridors, but throughout the entire school. His teachers tried to redirect him, sometimes even running after him as he slipped away again. But Liam wasn’t being defiant—he was curious, alert, and overstimulated.

His behaviour hinted at possible traits of autism, ADHD, or sensory processing differences. His deep fascination with written words may suggest hyperlexia, a condition often marked by an intense interest in language. His running, rather than misbehaviour, may have been a form of self-regulation—a way to escape the unfamiliar sounds, smells, and expectations of a new environment.

Weeks later, a quiet shift began. Liam started staying in his seat. He listened more closely. He began to participate in lessons. But this transformation didn’t come through discipline. It came through familiarity. Once the environment felt safe and predictable, Liam could let go of survival mode—and start to learn.

Neurodivergence and Neurodiversity: What’s the Difference?

These two terms are frequently used interchangeably, but they refer to different concepts—and understanding the distinction is essential for inclusive design.

Neurodivergence refers specifically to individuals whose neurological development and cognitive processes differ from societal norms. This includes people with autism, ADHD, dyslexia, dyspraxia, Tourette syndrome, and other conditions.

The term neurodiversity was coined and became well-known in the 1990s thanks to autism rights advocates like Jim Sinclair, Judy Sinclair and Donna Williams.

Neurodiversity is a broad concept that includes both neurotypical and neurodivergent individuals. It understands neurodivergence as the natural variation in how human brains function. Just as biodiversity strengthens ecosystems, neurodiversity acknowledges that cognitive differences are an essential part of what it means to be human.

Recognising this difference shifts the narrative from deficit to diversity—and opens the door to design that respects all minds.

How Environments Shape the Brain

Liam’s story reminds us of a powerful truth: the brain is shaped not just by genetics, but by the environment. From the earliest weeks of gestation, external factors influence how neural pathways form and function.

Nutrition, stress, exposure to toxins, physical activity, early relationships, and even architectural space—all play a role. During childhood and adolescence, these influences are especially potent, shaping not just cognitive development, but also emotional regulation, social capacity, and learning.

Each brain is unique. And the built environments we inhabit—homes, classrooms, streets—can either support or hinder that uniqueness.

Architecture is never neutral. It either enables or impedes.

It is essential to recognise that neurodivergent individuals possess a wide range of skills, strengths, and talents that can be highly valuable in various contexts. Some are exceptionally creative, have remarkable attention to detail, think in innovative ways, or demonstrate extraordinary memory, among other qualities.

Neurodivergent individuals can be highly intelligent, creative, analytical, empathetic, or gifted in ways that traditional systems struggle to recognise.

Rethinking Difference: Strengths of the Neurodivergent Mind

Neurodivergent individuals are not lacking intelligence or talent. On the contrary, many possess exceptional creativity, memory, focus, or pattern recognition. They may approach problems from novel angles or excel in areas where others struggle.

Yet, traditional systems often overlook or penalise these strengths. From rigid classrooms to overstimulating workplaces, many environments unintentionally exclude those who think differently.

This is why inclusive design isn’t just an act of compassion—it’s a gateway to unlocking human potential.

Brain and Built Environment

Scientific evidence confirms: the built environment affects our mood, cognition, and behaviour.

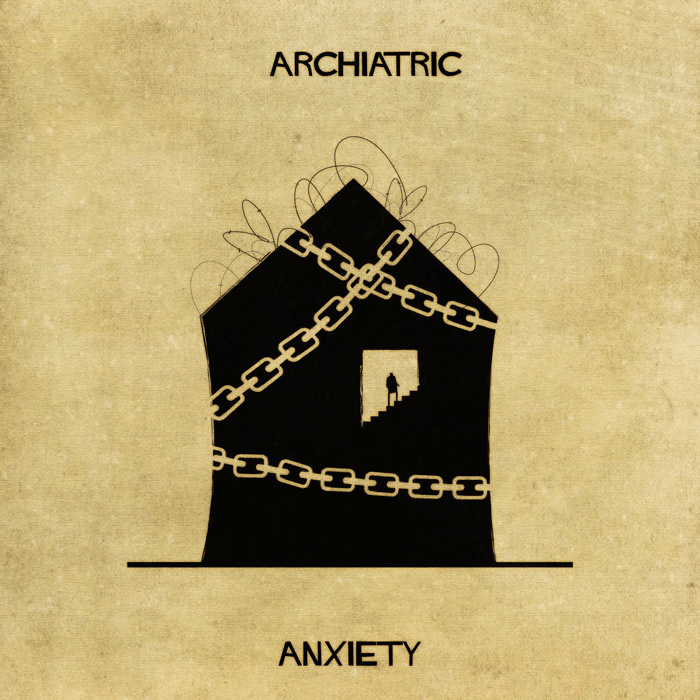

A sensory-rich space with calming sounds, natural light, and pleasant scents can support mental health and learning. But environments with noise, visual clutter, or poor spatial cues can overwhelm the senses—especially for neurodivergent individuals.

This makes the architect’s role not just functional or aesthetic—but neurological. These days, professionals are tasked with crafting environments that not only please the eye but also engage the mind and influence the emotions of those who inhabit them. By understanding the intricate relationship between space, light, and human psychology, architects have the power to design structures that can enhance well-being, productivity, and social interaction.

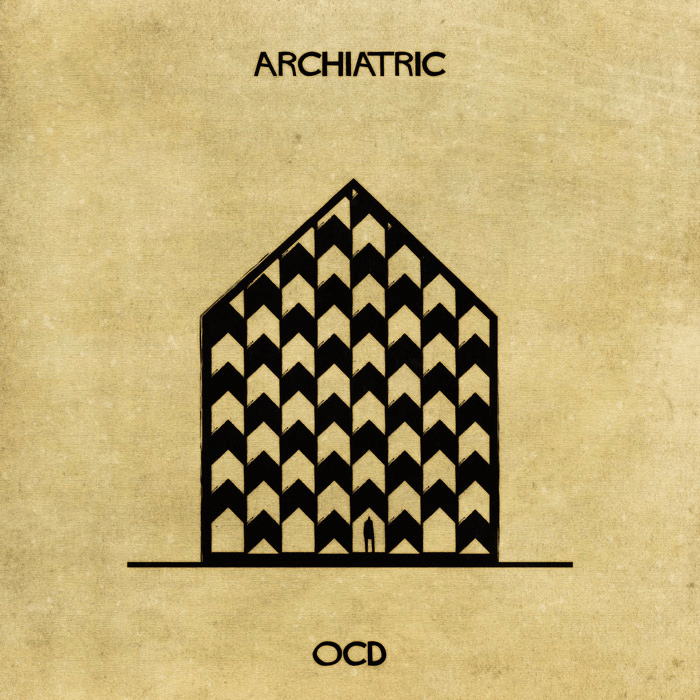

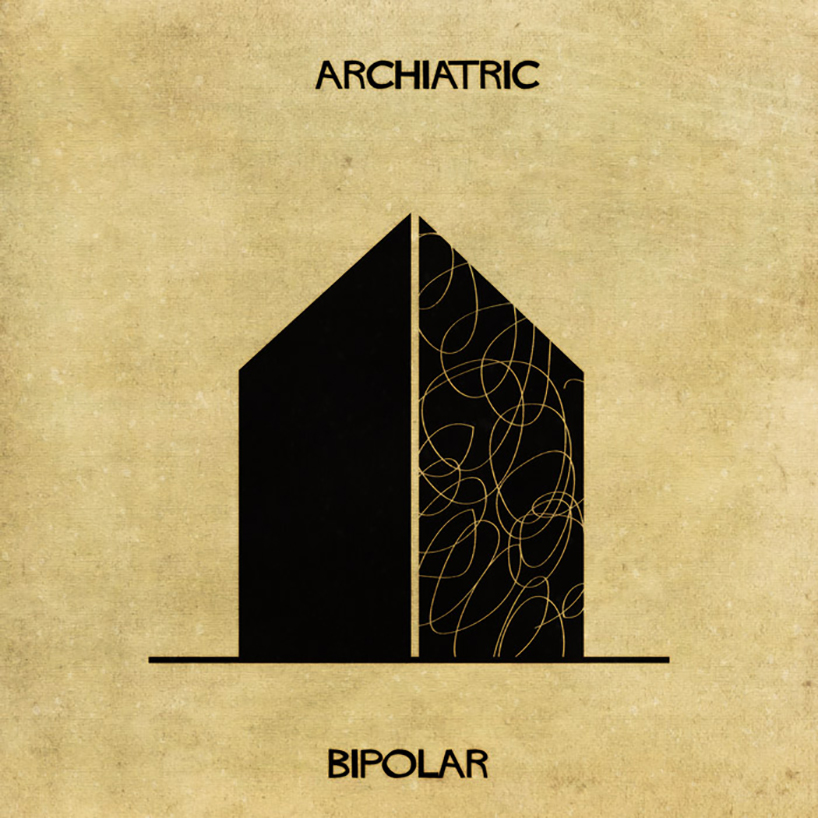

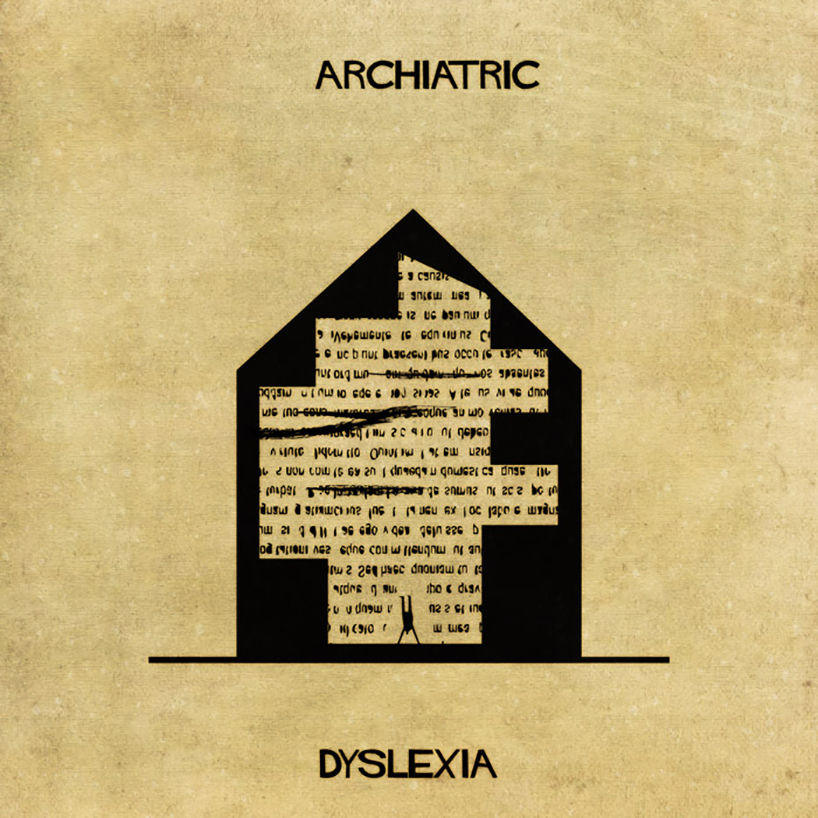

One powerful example is Archiatric by Federico Babina—a visual project that explores mental health through architectural metaphors, helping us visualise the unseen.

This series represents mental illnesses and neurological disorders through architectural metaphors.

How Many Are We Leaving Out?

To understand why inclusive design matters, we only need to look at the numbers.

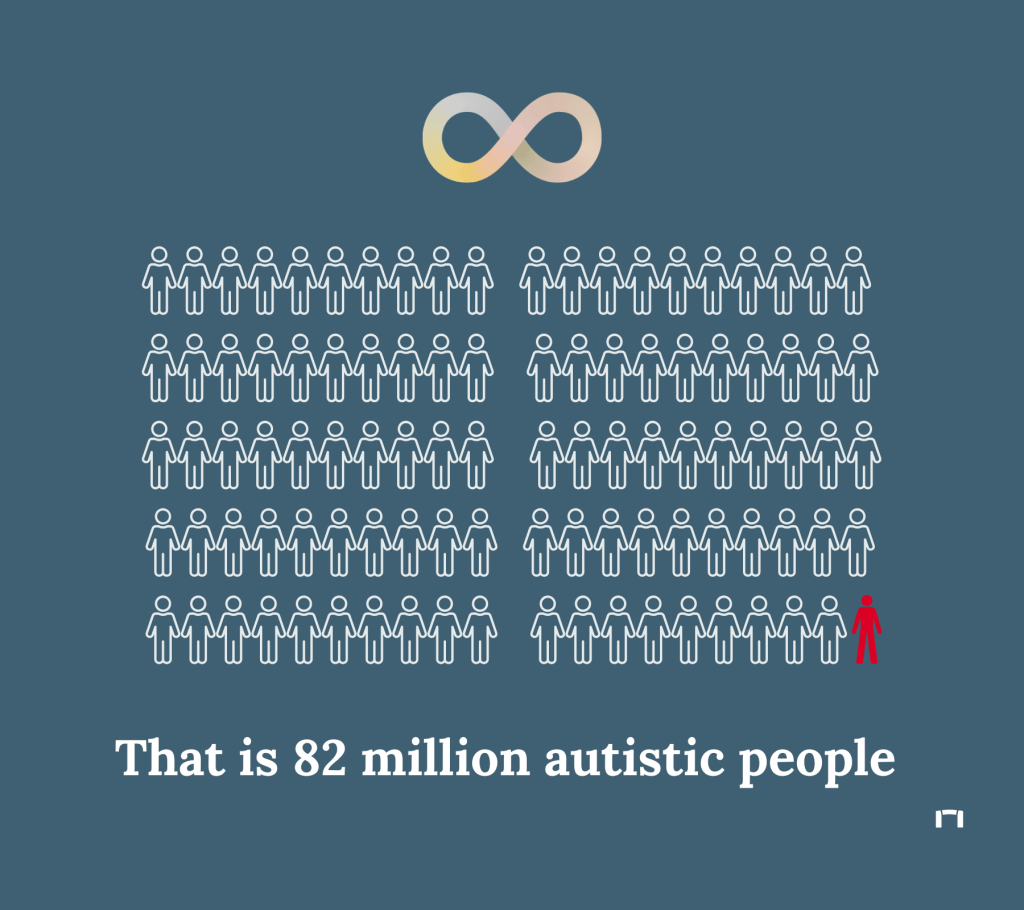

Deloitte estimates that 10–20% of the global population is neurodivergent. With over 8 billion people worldwide in 2025, that means 800 million to 1.6 billion individuals are navigating the world with brains that work differently.

Neurodiversity statistics in the UK reveal important insights into the prevalence of neurodevelopmental conditions among the population. The following figures show only the percentage of people with diagnoses; however, it’s crucial to note that the actual number might be significantly higher, as many adults remain undiagnosed due to various factors, such as lack of access to mental health services or societal stigma.

| Condition | Population |

|---|---|

| Dyslexia | 10% |

| Attention Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) | 3-4% |

| Dyspraxia | 8% |

| Dyscalculia | 6% |

| Generalised intellectual disability | 3% |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | 1% |

Source: ADHD Aware.

Design Challenges: When Architecture Overwhelms

Too often, environments ignore how different brains process the world:

- A cluttered street sign may be unreadable for someone with dyslexia.

- Irregular patterns or chaotic materials may provoke anxiety for someone with OCD.

- Symmetrical, echo-filled corridors may disorient people with autism, ADHD, or dementia.

These are not rare exceptions. They are everyday barriers.

Architecture that fails to consider neurological diversity inadvertently marginalises millions.

So we must ask: Who are we designing for—and who are we leaving out?

1. A traffic sign can be read wrongly by someone with dyslexia.

2. A mix of patterns, textures, and materials can cause frustration and extreme anxiety for someone with OCD

3. Symmetrical and minimalist corridors can disorient people with autism, ADHD, or dementia, where repetition and uniformity may become confusing rather than calming.

Towards Inclusive Design: A Call to Architects

Designing for neurodiversity is not just a technical challenge—it is both an ethical responsibility and a creative opportunity.

As Liam’s experience reminds us, when the environment becomes predictable and emotionally safe, engagement and learning can finally begin.

In schools, this might mean colour-coded signage, acoustic zoning, and gentle transitions. In workplaces: flexible seating, natural light, and quiet zones. In hospitals: softer materials, clear spatial orientation, and reduced sensory triggers.

These aren’t luxuries. They are the foundations of universal design—spaces that work for as many people as possible, without requiring adaptation or apology.

Architects and designers have the power to shape environments where everyone—regardless of cognitive profile—can feel capable, safe, and included.

Inclusive design isn’t just about accommodation.

It’s about reimagining the world—with every brain in mind.

References

ADHD Aware. (n.d.). Neurodiversity statistics in the UK. Retrieved from https://www.adhdaware.org.uk

Sinclair, J. (1993). Don’t mourn for us. Retrieved from https://www.autreat.com/dont_mourn.html

Babina, F. (n.d.). Archiatric: Architectural interpretations of mental illness. Retrieved from https://www.federicobabina.com

Will.i.am opens up about his battle with ADHD and how he was once pronounced dead https://metro.co.uk/2018/01/21/will-i-am-opens-up-about-his-battle-with-adhd-and-how-he-was-once-pronounced-dead-7246679/#:~:text=He%20said%3A%20’I’ve,drowned%20in%20a%20swimming%20pool.

Keanu Reeves Dyslexia https://dyslexiahelp.umich.edu/keanu-reeves#:~:text=Despite%20being%20expelled%20and%20struggling,an%20injury%20prevented%20this%20dream.

Elon Musk opens up on how Asperger’s has impacted his life https://www.axios.com/2022/04/15/elon-musk-aspergers-syndrome

Why do architects need to understand neurodiversity? https://www.ribaj.com/intelligence/why-do-architects-need-to-understand-neurodiversity#:~:text=Neurodegenerative%20conditions%2C%20such%20as%20Alzheimer’s,any%20cognitive%20profile%2C%20including%20neurotypical.

Neurodiversity As A Strengthening Point For Your Team And Our Society https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2021/08/13/neurodiversity-as-a-strengthening-point-for-your-team-and-our-society/

Barrier-Free MD. (n.d.). Neurodiversity vs. Neurodivergence – Understanding the Differences. Retrieved from https://www.barrierfreemd.com