Imagine walking down a poorly lit corridor, where every door looks the same, fluorescent lights buzz overhead, and your footsteps echo in the void. You pause. Where should you go? Your body tenses even before you think.

Now contrast that scene with entering the atrium of a library filled with natural light. A central spiral staircase rises before you, architectural landmarks guide your way, and warm materials soften the noise. Without words, the space tells you where you are, where to go, and how to feel.

This is the terrain of neuroarchitecture: the study of how built environments shape brain processes, emotions, and behaviour. A recent review by Abbas et al. (2024) synthesises what neuroscience reveals today about our daily interaction with architecture.

How does the brain understand architecture?

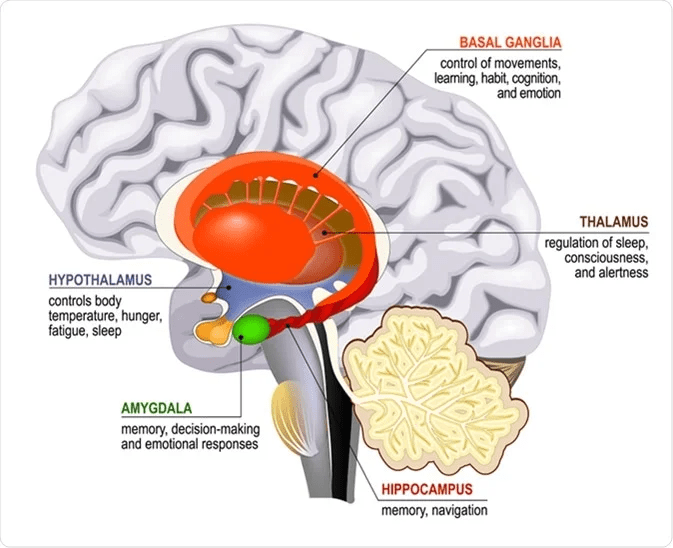

We do not simply see buildings; we process them through specialised neural systems.

- The parahippocampal place area (PPA), located adjacent to the hippocampus, links visual perception with spatial memory. It helps us recognise places, orient ourselves, and recall routes. In architecture, this means that spaces with clear landmarks and legible forms facilitate the creation of mental maps, reducing disorientation and improving user experience.

- The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is highlighted as key in neuroarchitecture, acting as a bridge between emotion and cognition. It integrates what we perceive with how we feel, regulating attention and emotional control. Studies indicate that it responds to features such as curvature, transitions, and spatial fluency: coherent, harmonious environments support its regulatory role, while fragmented or overloaded spaces heighten tension.

- Mirror neurons also play a role. They activate both when we perform an action and when we observe it, allowing us to “simulate” what we perceive. In architectural contexts, this means that when we see a corridor, a staircase, or a vaulted ceiling, our brain does not only register its form—it also activates motor and emotional patterns associated with how it would feel to move within that space. This embodied simulation explains why certain designs invite movement or convey calm, while others provoke discomfort or resistance.

In this sense, architecture is not static: it is a constant dialogue with the nervous system, shaping our sense of safety, comfort, or stress.

How do we orient ourselves in spaces?

Wayfinding is not just a matter of convenience; it is neuroscience in action. The hippocampus generates cognitive maps with “place cells” that encode spatial positions.

When a building offers clear landmarks, coherent routes, and comprehensible layouts, the brain navigates with ease. But in monotonous or overly complex spaces, cognitive load rises, stress increases, and users—particularly people with dementia or autism—may feel disoriented.

Hospitals, airports, and universities are frequent settings where poor wayfinding design becomes a barrier to accessibility.

Architecture whispers to the senses and leaves traces in the brain.

How do spaces influence our emotions?

Environments also have a direct influence on our emotions: they can evoke memories, inspire creativity, or even generate anxiety. Therefore, it is essential to pay attention to our surroundings and how they affect our emotional well-being, seeking to create spaces that promote positivity and calm.

- Light: natural light supports circadian rhythms, while excessive artificial lighting disrupts sleep and mood.

- Colours and materials: warm textures offer comfort; sterile or monotonous palettes can alienate.

- Nature: views of greenery reduce stress; its absence heightens anxiety.

- Acoustics: reverberant noise unsettles; absorbent surfaces calm the nervous system.

Functional MRI studies confirm that pleasant, coherent environments activate brain regions linked to positive emotion more strongly.

Architecture speaks to the senses and to the brain. Designing with the wellbeing of the brain in mind is not a luxury: it is the key to creating spaces that truly transform us in positive ways.

Designing with the brain in mind is not a trend; it is the key to creating environments that truly transform us in positive ways.

What does it mean to design with neuroscience in mind?

The evidence is clear: architecture is not neutral. It regulates emotion, cognition, and health. Yet, there is no universal formula. Preferences are shaped by culture, memory, and neurodivergence.

For designers, this calls for an empathetic, evidence-based practice. Key guidelines include:

- Prioritise clarity and coherence in layout.

- Incorporate refuge zones within busy environments.

- Balance natural and artificial light to support circadian health.

- Integrate nature and texture as sensory anchors.

- Design with flexibility, allowing adaptation for diverse users.

Conclusion – Designing with the brain, not against it

We spend up to 90% of our lives in built environments. Every corridor, classroom, or bedroom leaves a trace on the brain—calming, confusing, or inspiring. It is not just about walls or ceilings: it is about atmospheres that shape emotions, influence memory, and regulate wellbeing.

The challenge of architecture today is to recognise that power and embrace the responsibility it carries. A building is not merely a functional container but a living interface with the human mind. Its design can enhance concentration or scatter it, induce calm or anxiety, facilitate orientation or generate confusion.

As Abbas et al. (2024) remind us, neuroarchitecture is still evolving. Yet one truth is already evident: when we design with the brain in mind, we design for life itself. In a world where mental health challenges are a growing reality, we cannot remain on the sidelines.

If we are not part of the solution, we inevitably become part of the problem.

And the question remains: what imprint will your architecture leave on the minds of those who inhabit it?

Reference

Abbas, A., Nazir, A., Habib, A., & Arif, M. (2024). Neuroarchitecture: How the perception of our surroundings impacts the brain. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11048496/